Sanitary Tortilla Factory, Albuquerque

July 13 – August 13, 2018

“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” quoth J. Robert Oppenheimer from the Bhagavad Gita. This line of Hindu scripture is what came to mind, Oppenheimer later claimed, as the first detonation of a nuclear weapon unfolded before his eyes. His revelation was calculated mythmaking—a bid to bind carefully chosen words to an iconic array of images. It’s a feat of forced perspective that still holds incredible sway over how we interpret the event. An excerpt from the quote appears on the poster and in the libretto for Santa Fe Opera’s production of the Manhattan Project–themed Doctor Atomic.

It’s also referenced in the title for Nora Wendl and Mitchell Squire’s joint exhibition. Both are artists and architects—she teaches architecture at University of New Mexico, he at Iowa State University—and their practices are grounded in fastidious scholarly research. They drop a bomb, or rather, the bomb, at the heart of the show.

In an installation piece by Squire, vintage glass bottles and vases in positively nuclear colors cluster on a mirror atop a scuzzy scrim made from packing tape and wax paper. The backdrop to this weird stage is an enormous image of the Trinity test, digitally altered to match the startling palette of the glassware. The slender necks of the vessels mirror the shape of the rising plume behind them.

The radioactive poison of a high crime against humanity has trickled and pooled into these quirky vessels.

Squire’s piece, titled all your fears are caused from novel reading, marks the beginning of the exhibition’s timeline and elegantly fleshes out its central conceit: the “beautiful test site.” The artist has flattened a moment of great historical rupture into a stage set, reimagining a staggering tragedy as a mundane domestic comedy with a colorful cast of midcentury design objects. The radioactive poison of a high crime against humanity has trickled and pooled into these quirky vessels. Who knew a vintage store shelf could bear the crushing weight of modern history?

The rest of the show examines other mid-century set pieces—large and small cultural testing grounds—that shaped material culture at the time and have influenced dominant notions of American history and identity ever since.

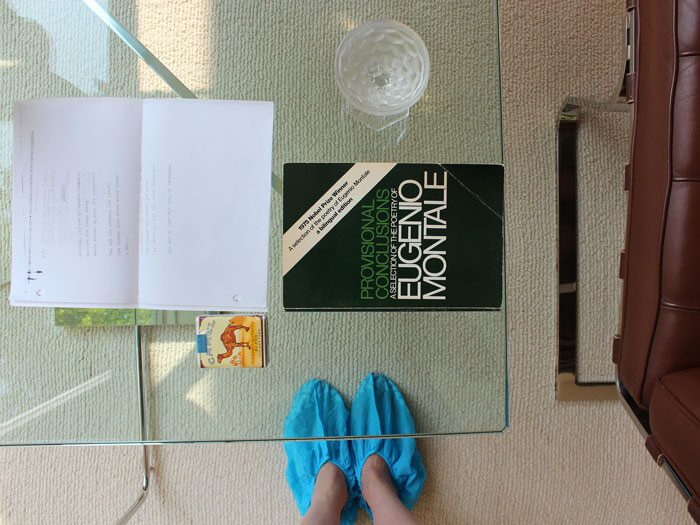

Wendl presents five photographs on glass titled I Listened, which show a woman in a black dress wandering through architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. The glass-walled mansion is a mid-century magnum opus designed and built between 1945 (the year of the Trinity test) and 1951. It was the residence of Dr. Edith Farnsworth, Mies’s sometime lover and most influential patron.

Could these be historic images of a young Farnsworth in her fortress? The woman wears a 1940s-style dress, but her powder-blue shoe covers and fluffy black headphones betray her as a modern-day intruder. The woman in the photographs is Wendl herself, who, through a feat of academic bartering, was granted sixty minutes alone in the house (now a museum to Mies).

The works confront the erasure of women from history—or their relegation to the periphery of many a beautiful test site—to make room for the enduring myth of the solitary male genius.

In an artist statement, Wendl reveals that she was recording audio throughout the sojourn. She points out that, despite the home’s sweeping views of its surroundings, its thick glass walls prevented her from capturing natural sounds. Mies’s design becomes a metaphor for humanity’s alienation from the environment, initiated by industrialization and punctuated by the earth-shattering detonation of the bomb.

A second body of work by Wendl, called Any woman in the company of this house, is a companion to I Listened. Using found images overlaid with vinyl text, Wendl fastidiously chronicles her hunt for photographs of Farnsworth, who is often misidentified by scholars despite her profound influence on mid-century modern architecture. The works confront the erasure of women from history—or their relegation to the periphery of many a beautiful test site—to make room for the enduring myth of the solitary male genius (à la Oppenheimer).

Squire’s series of found photographs in gilded frames titled here’s the thing for which you’re wishing rounds out the conversation. Culled from the mid-century oeuvre of Squire’s in-law, who was a hobby photographer, the images are idealized portraits of young white women with handwritten titles including Teen-age Smile and Modern Art Forms. Here, the female body is a test site to be shaped and exhibited by men and viewed intently by other women.

Through the lens of this exhibition, the postwar era sprawls onwards into the 21st century. The bomb’s metaphorical fallout never subsided. With clarity, Wendl and Squire tug the conversation forward by confronting demons that our nation never vanquished.