Shepard Fairey was nearly censored at the Mesa Arts Center. He’s back with a monumental artwork—and thoughts on police power, fascism, and art as a “counterwind.”

MESA, AZ—Artist Shepard Fairey recently created his first Arizona mural, at the arts center where his work was nearly censored by city officials in 2023. Now, he’s not only reflecting on the mural’s meaning, but also speaking out about the controversy involving his 2023-2024 exhibition in Mesa and the role of public art in countering political power grabs.

Fairey painted his Interdependent Nature mural on the west side of the city-owned and operated Mesa Arts Center campus in mid-April, opting for a geometric design with symbolism meant to convey themes of peace, justice, and interconnectedness.

“I hope the mural inspires people to think about how interconnected and delicate things are, because in many ways we’re resilient but also fragile,” he explains.

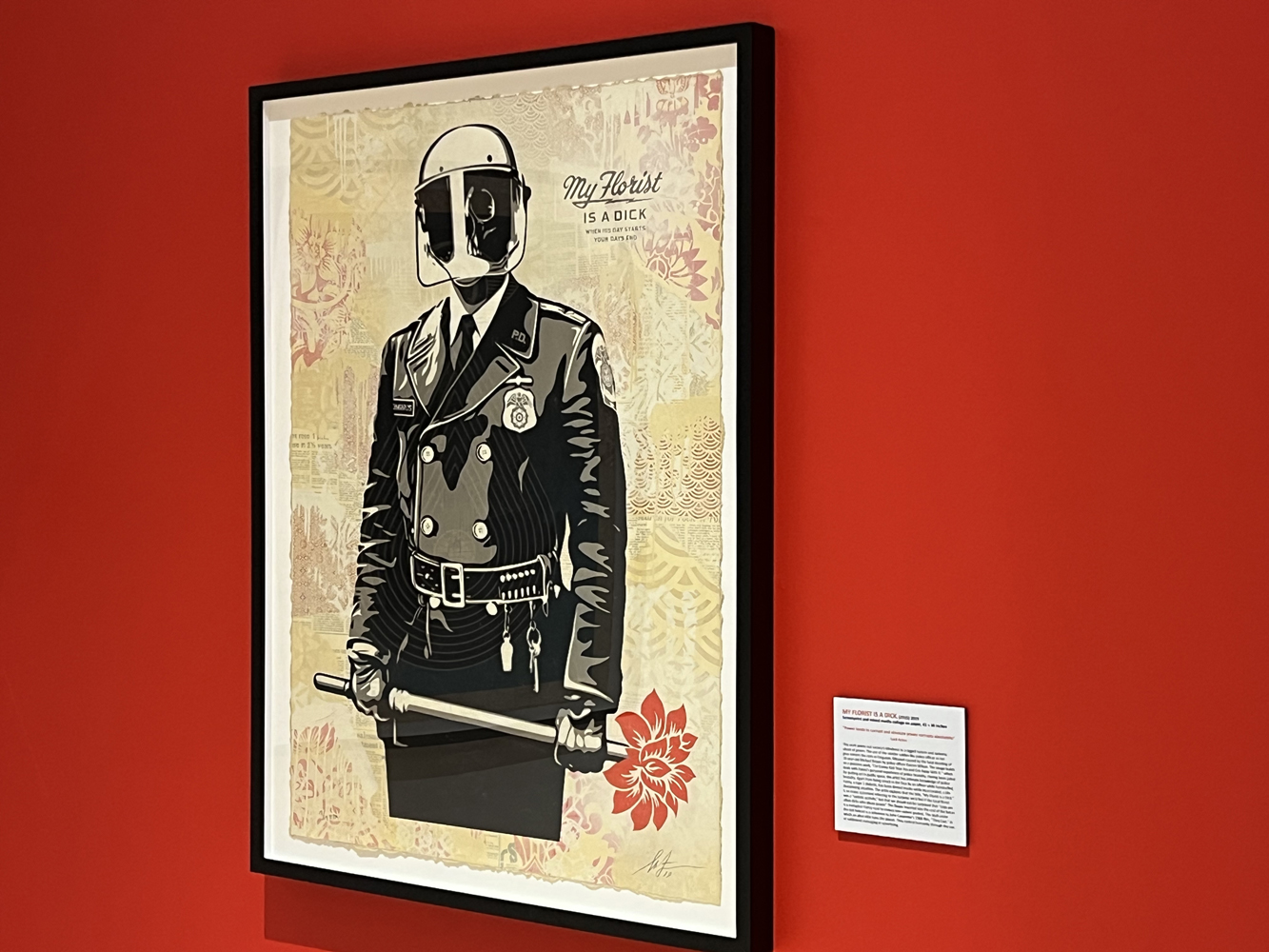

The venue is home to Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, which presented Fairey’s solo exhibition Facing the Giant: 3 Decades of Dissent from October 7, 2023 to January 21, 2024. The exhibition included his 2019 print My Florist is a Dick depicting an officer with a skeletal face dressed in riot gear, which was nearly pulled before the show opened over city concerns that it implied disrespect for local law enforcement.

“I don’t consider My Florist is a Dick to be one of my more controversial pieces,” says Fairey, noting that he’s been arrested eighteen times for street art. “It’s a fairly tame critique.”

Though they ultimately allowed the work’s display, the city posted a pro-police statement in the MCAM lobby during Fairey’s exhibition, and mounted the work in a corner of the gallery where it could easily be overlooked.

Neither Fairey nor Tiffany Fairall, the museum’s chief curator at the time, spoke publicly about the censorship controversy when it occurred. But public records indicate that the city manager’s reservations about the print led to significant changes in the museum’s fall season, including delaying exhibition start dates. Two Indigenous artists opted not to present solo exhibitions as planned, and Fairall resigned from her position and filed a federal lawsuit against the City of Mesa.

Today, Fairey says he faults the city’s police department rather than the city for the dust-up over My Florist is a Dick. “Part of the problem is police power,” he says. “I was grateful for everyone who said to keep the piece in the show. There’s power in numbers.”

Fairall ultimately decided to drop her lawsuit, but has been giving voice to her curatorial experiences through social media—explaining, for example, that she declined a settlement because it would have required signing a non-disclosure agreement. On April 21, 2025, Fairall published a Facebook post that set her own experience with censorship in the context of current events, writing this in part: “It is not easy speaking up. The power structure wants you silent and will intimidate and exploit your vulnerabilities to keep you that way.”

Despite the controversy, Fairey says he was excited to create the mural in Mesa for several reasons, including the fact that he’s got several collectors and friends—including graffiti artist DOSE—in Arizona. Other artists who stopped by while Fairey worked on the piece included Phoenix-based Jeremie “Bacpac” Franko, one of many locals who’ve taken inspiration from Fairey’s work.

Fairey’s mural spans two exterior walls along Center Street south of Main Street—one 38 by 34 feet, and the other 32 by 44 feet. “The walls are irregularly shaped, which is really cool for the art,” says Fairey, whose design includes large blocks of color, as well as several symbols that recur frequently in his expansive body of work, including the scales of justice and a peace dove.

“I try to infuse my public art pieces with things that matter to me and should matter to the whole community,” says Fairey. “Knowing Mesa has a climate action plan, and climate change being one part of my portfolio and pursuit of justice, I thought it would be great for that to be the dominant idea.”

The artist’s own experience of climate change impacts include facing early-2025 wildfires in Los Angeles, the city he calls home.

Fairey spoke with me the day after finishing his Mesa mural, sharing insights about the concepts at its core. “If we treat each other the way we want to be treated and treat the planet in ways that it will be good to us for years to come, that’s a major part of achieving peace and harmony.”

The mural also alludes to Fairey’s take on the exhibition controversy.

“Through communication and diplomacy and problem-solving, adversity can lead to positive growth and healing,” he says. “These ideas are implied, but they’re not heavy-handed.”

Large geometric compartments within the design are meant to suggest the idea of “disparate parts coming together in harmony and symphony.” Fairey adds, “How you put things together is what makes it work; it’s overt and it’s subtle.”

Of course, the mural also exists in the wider context of the national political landscape. It’s a topic that Fairey tackles with enthusiasm.

“I’ve understood that Donald Trump has fascist, autocratic tendencies since before he was elected the first time but he’s emboldened now,” reflects Fairey. “There’s always a suppression of art and creative expression with the sole exception of people who are willing to create propaganda for the regime.”

Fairey has created countless portraits of politicians, agitators, and resisters—including Chinese artist Ai Weiwei and former Supreme Court associate justice Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In 2008, he created the iconic HOPE poster for Senator Barack Obama’s first U.S. presidential campaign.

“Artists are often seen as the conscience of society as well as the early warning mechanism, so it doesn’t surprise me that Trump wants all artists and other creatives to be less powerful and stifled,” Fairey says. “How can the mural not stand as a beacon of resistance to the Trump mentality and the counterwind to everything he is trying to do?”

Still, Fairey takes a wider view of the mural’s significance, rooted in his approach to making public art.

“A lot of people are intimidated by art in museums and galleries, especially if they don’t have an arts background or education,” he says. “We have to bring art to the people where they live, so they get used to the idea of being justified in caring and talking about art.”