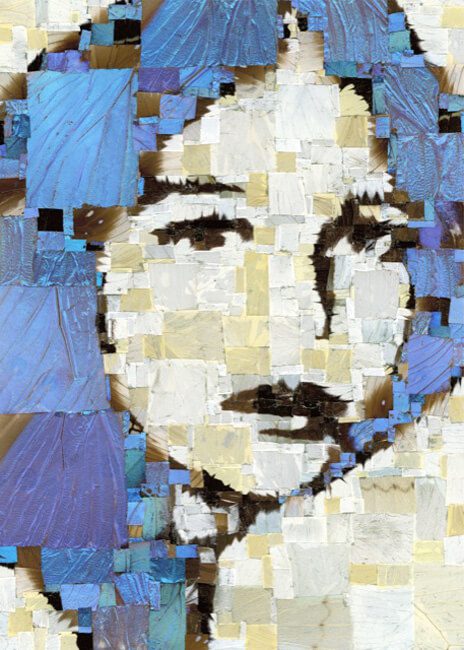

Benjamin Timpson hand-cuts delicate pieces of ethically-sourced butterfly wings to create meticulous and moving portraits that explore trauma and healing while raising awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women.

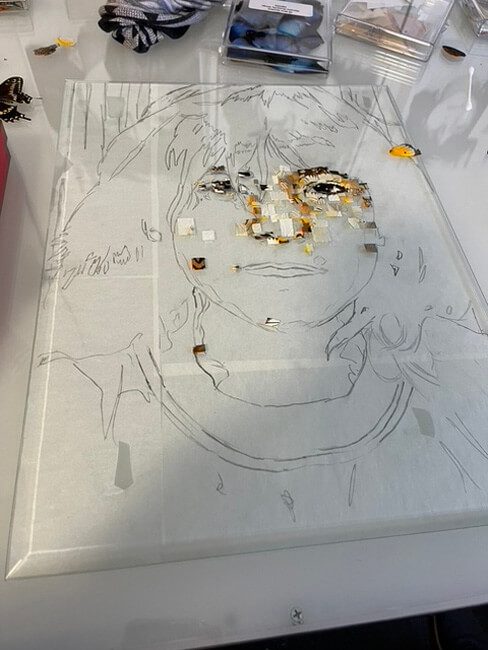

The partially-completed image of a young girl named Rhia lays surrounded by delicate butterfly wings atop a table in the small home studio where artist Benjamin Timpson uses the wings to create meticulous and moving portraits meant to raise awareness about missing and murdered Indigenous women. Rhia was just seven years old when she was raped and murdered.

The Arizona-based artist has been working on Rhia’s portrait since October 2021, mindful of the trauma experienced by Rhia’s mother Elaine. Timpson talks with surviving family members, making sure he has their approval before starting a new portrait. “The loss never goes away, but I hope the portraits can somehow help with healing,” he says.

“This is happening all over the country, but it’s so underreported,” Timpson told Southwest Contemporary in early February 2022 during a Saturday morning visit to his Tempe studio, where he talked about the ways healing, beauty, hope, and change inform his work.

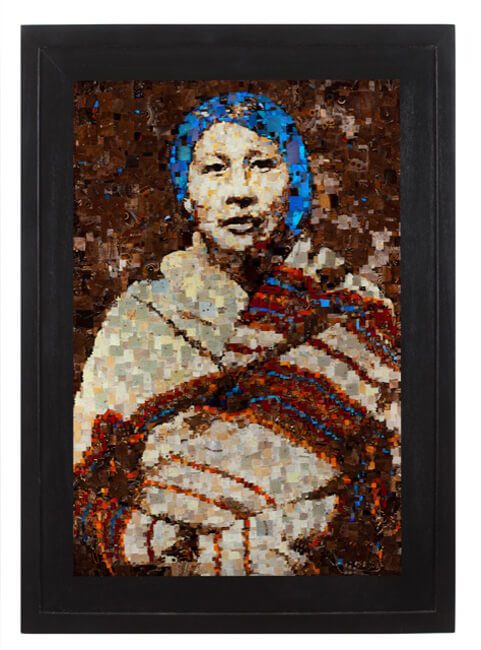

Rhia’s portrait will become part of Metamorphosis, a series started in 2017 that also includes women who’ve experienced sexual or domestic violence, including Caroline Felicity Antone. Timpson learned of Antone’s story around the same time as when a family member’s DNA test confirmed Timpson’s own Indigenous heritage, which the artist traces to Puebloan peoples.

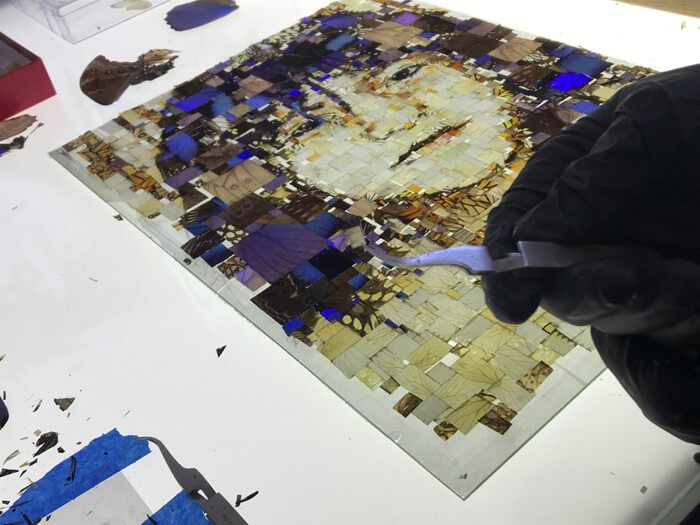

Timpson starts most days in his studio with quiet morning hours to methodically piece together the portraits, working from photographs of his subjects while wearing gloves and a covering over his nose and mouth—the butterfly wings are so delicate that his breathing can cause them to scatter. Closet shelves are filled with art supplies including the wings ordered online that arrive from butterfly farms in small, clear plastic packets.

“Butterflies are a symbol of healing,” Timpson says of choosing this particular medium to create portraits of missing and murdered women. “In Japanese culture, butterflies represent the souls of lost loved ones.” He’s used the wings before, fascinated at first by properties of line and color, and the translucence that gives them a liminal quality when they interact with the light.

Timpson cuts the wings with razor blades, making small squares or other shapes, then uses tweezers to move them into place and a handmade tool to apply the dab of acrylic liquid that affixes them to glass panels. Asked how many wing pieces comprise a typical image, Timpson pauses to count along both a vertical and horizontal edge of Rhia’s twelve-by-sixteen-inch portrait, estimating that it’ll include over 2,000 pieces.

Rhia’s portrait is taking shape on one of two light tables that Timpson built with bamboo, which the artist can adjust to various heights. At the time, he needed a sizeable surface to create Rita Smith, the two-by-three-foot portrait that took a full year to complete and his largest Metamorphosis artwork to date.

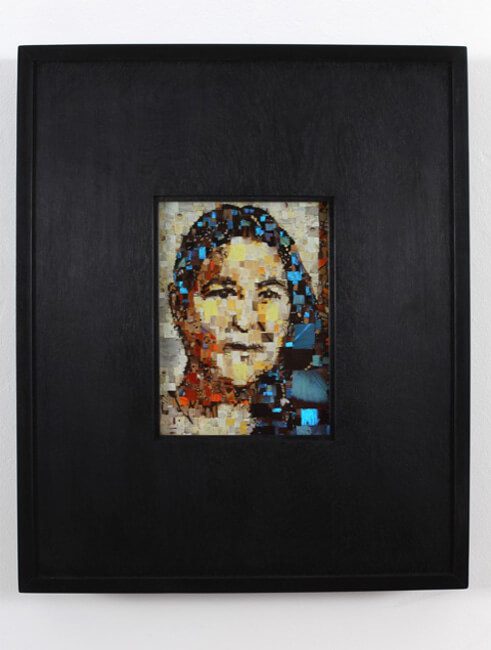

The compositions are titled after the girls and women they portray, including Aielah Saric-Auger, Rosetta Peters, Rebecca Plentywounds, and Shayna Gold. Sometimes their identities aren’t known, so the series also includes Banff County Jane Doe and Pima County Jane Doe.

Typically, the finished pieces are backlit so the portraits can be illuminated, a technique that amplifies their visual impact.

Beyond the studio, there’s ample evidence of Timpson’s larger body of work, which includes additional photographic projects as well as paintings and sculptures. Some are displayed in common areas, while others are stored in plastic crates or metal cabinets with thin drawers.

Artbooks fill several bookcases, their titles often referencing the artists Timpson credits with influencing his own creative practice: Andy Goldsworthy, Gustav Klimt, Saul Leiter, Georgia O’Keeffe, Amedeo Modigliani, Vic Muñoz, and many more.

Other inspirations include photographers Liz Cohen and Mark Klett, both recipients of the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and fellow faculty members at Arizona State University’s School of Art, where Timpson has taught since fall 2019. Both Klett and Timpson are represented by Lisa Sette Gallery in Phoenix.

In many ways, the Metamorphosis series reflects Timpson’s philosophy of making art and experiencing visual culture. Sitting at a round table near glass doors leading to his backyard, Timpson talked of art as a universal form of memory, healing, and connection.

“I want my portraits to come from a place of real emotion, but it’s the culture that carries that through time and space, not the artist,” he says. “I try to make work that’s beautiful and accessible, so people can come to it at their own speed and feel like they’re part of a conversation.”

His own artistic journey began during early childhood when his mother taught him to use watercolors. By age seven, he was taking lessons in oil painting. He loved taking pictures, too, sometimes borrowing his dad’s Olympus camera, but also recounts the longtime fascination with bugs that’s shaped his creative practice.

Today, his work with butterfly wings focuses on particular individuals while also embracing a wider lens. “I want people to see how beautiful these women are, and how sacred all women are.”

Timpson’s work will be part of the Wear Your Love Like Heaven group exhibition at Lisa Sette Gallery, 210 East Catalina Drive in Phoenix. The show is scheduled to run from March 12 through May 28, 2022.