Lisa Sette explores contemporary society by curating compelling exhibitions characterized by conceptual and aesthetic rigor at Lisa Sette Gallery in Phoenix, Arizona.

Sculptures made with synthetic hair and metal braid clamps hang suspended from the ceiling inside Lisa Sette Gallery, where viewers also see prairie-style bonnets created with thousands of pearl corsage pins. It’s a fascinating pairing of works by collaborators Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Fresquez, who created the sculptures, and Angela Ellsworth, who fashioned the bonnets for the exhibition Things We Carry curated by Lisa Sette.

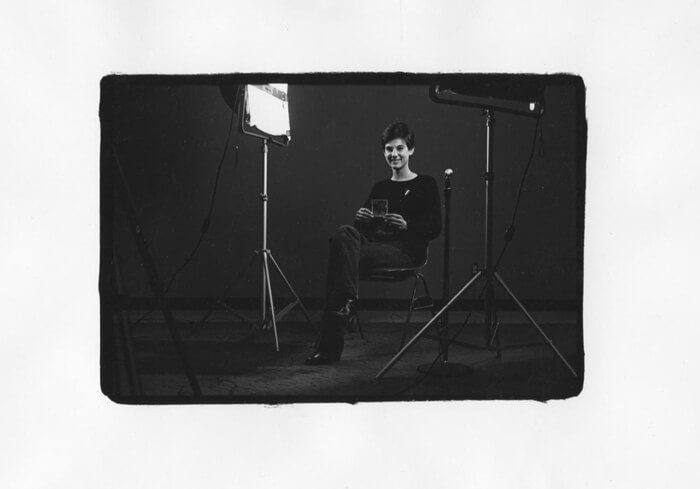

Sette has curated exhibitions for her eponymous gallery since 1985, showing artworks distinguished by their conceptual and aesthetic rigor. Today, the gallery is housed in a renovated Al Beadle building in midtown Phoenix, where visitors descend a small flight of concrete steps to enter the semi-subterranean space that resembles a pristine white box.

Sette opened the space (210 E Catalina Dr) in 2014 after twenty-eight years in Old Town Scottsdale, where the once-robust gallery scene has been diluted by retail and restaurants. The gallery’s first incarnation was housed inside the historic Andre Building on Mill Avenue in Tempe.

“I was in my mid-twenties at the time,” Sette recalls. “I didn’t really know a lot about contemporary art. I just knew that I wanted to show art that was markedly different than what was being shown.” Her first curatorial experience was a group show featuring several of her peers, set up inside the living room of a Tempe house she shared with six roommates.

Today, Sette represents more than three dozen artists, including Sonya Clark, Luis González Palma, Julianne Swartz, and James Turrell. Several of the first artists she represented, including William Wegman and Mark Klett, are still with her today. Many are internationally renowned.

Currently, about a third of the artists on Sette’s roster are based in Arizona. She periodically puts out a call inviting artists to submit their work for consideration. “It’s particularly helpful in finding what you don’t know you’re looking for, and in knowing what’s going on in the community,” she says.

Even so, she’s found most of the artists she works with by other means, such as exploring galleries in other cities and traveling to international and national art fairs. “I’m always looking, and sometimes I find things outside the normal route,” she says. “Gallerists are on the front lines of exploration.”

Sette values originality, but also depth and breadth of subject matter as well as distinctive materiality. “I look for something visually arresting, something that I haven’t seen before,” she says. “I’m intrigued by things that I don’t fully understand when I first see them. I want art to teach me something.”

She has an eye for pieces that are “impeccably well-crafted,” but says “the medium has to be right for the message.” For Binh Danh, an artist with Vietnamese roots, the work includes daguerreotypes with mirrored surfaces that suggest viewer complicity in scenes of genocide and war.

“I really enjoy artists and working with them,” Sette says. “They’re personally memorializing a moment in time, making a record of our history. I respond to that way of making your mark in the world.”

Part of Sette’s curatorial practice includes showing work by artists she doesn’t represent.

In 2018, Sette curated Confess, an exhibition of works by Los Angeles-based artist Trina McKillen, who created an exquisite life-size glass confessional confronting pedophilia and complicity within the Catholic church, informed in part by growing up in Belfast, Northern Ireland during the 1960s.

Sette hails from Connecticut and moved from New Haven to Arizona as a college student after reading a book by renowned photographer Bill Jay. “He was teaching the history of photography at Arizona State University and I decided that I should go there,” she recalls. “I was ready to leave the East Coast.”

She also studied art history and studio photography, but never considered herself an artist. “By the time I did my undergraduate show, I felt like I wasn’t that good at it. I wasn’t feeling like I had a whole lot to say.”

Turns out, she has plenty to say.

During the past five years, for example, she’s curated several exhibitions that speak to the country’s political landscape. “It was my form of activism, I guess.”

In 2017, she sought to convey a sense of shared humanity in Tell Me Why, Tell Me Why, Tell Me Why (Why Can’t We Live Together?), an exhibition titled after lyrics for a 1972 Timmy Thomas tune. In 2019, she explored the aesthetic, ideological, and societal constructs around whiteness for a group exhibition titled Subversive White.

Recurring themes in her curatorial choices include human impacts on the environment, evidenced in works by Beijing-based Yao Lu and Indiana artist Michael Koerner that she’s shown in recent years. In October, she’ll open the Temporary in Nature exhibition featuring eleven artists whose work elucidates both the perils and opportunities of the Anthropocene era.

Next spring, she’ll present Wear Your Love Like Heaven, a group exhibition titled after a 1967 Donovan song, which will address the ways love and protest are intertwined.

“Instead of cynicism and pessimism, I want to lean more towards optimism and lightness, imagining what the world would be like if we were all more tolerant and kinder,” she says. “We need a new tipping point here.”