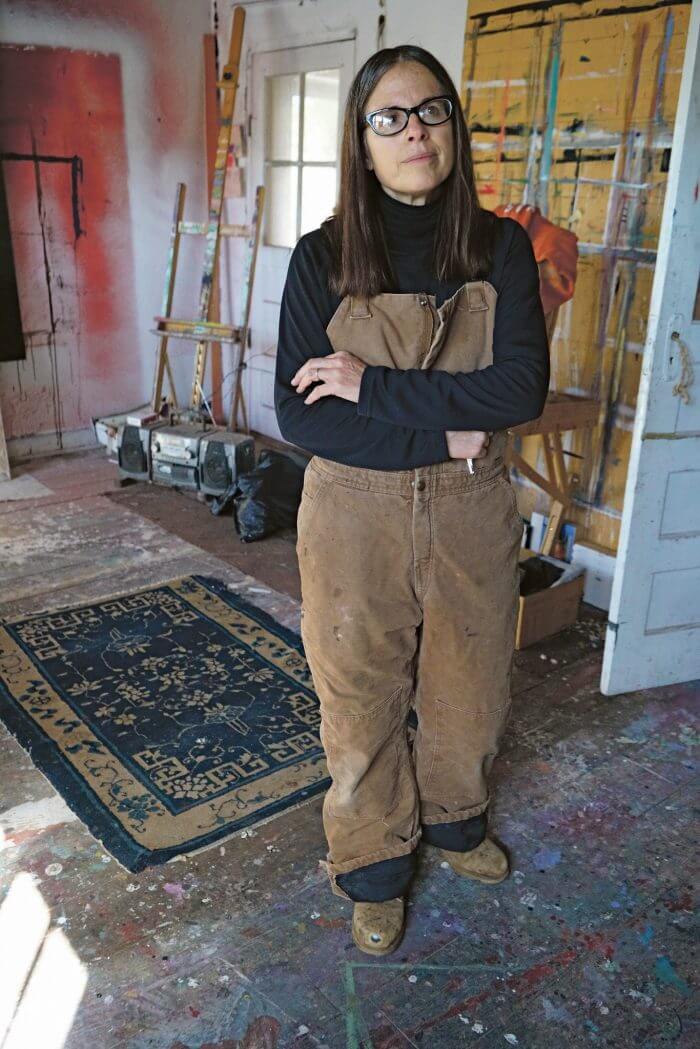

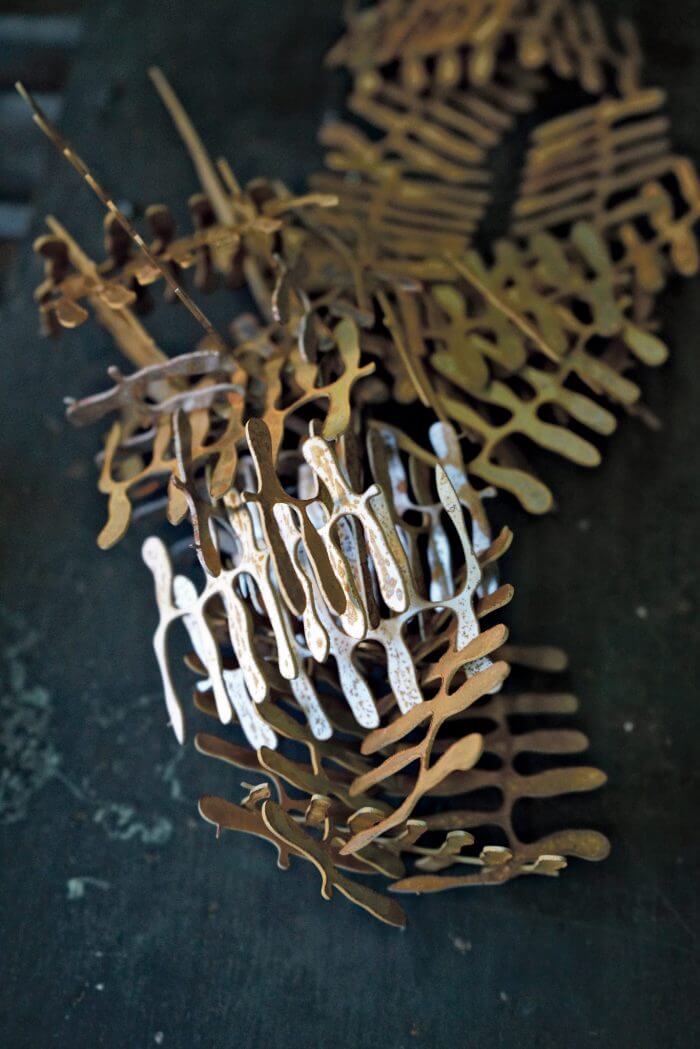

Paula Castillo is a priestess of postmodern metallurgy, recombining the scrap and detritus of Industry into abstract sculptures that quietly reckon with earth and man. A metallurgist only in a poetic, alchemical sense—she’d be quick to tell you the technical and conceptual distinctions between welding, blacksmithing, and more—she prefers the practice of additive welding for her own work. Castillo’s sculptures manage to turn steel byproduct into morphous shapes that are often organic or animated. Her materials are repurposed and recycled, yet the past lives and stories of the scrap lurk and echo within like an untold story of aspiration and waste. We visited the artist at her studios in the picturesque village of Cordova, a short jaunt from the High Road to Taos.

Lauren Tresp: Why are you here in Cordova?

Paula Castillo: I came to Cordova in 1985—was it ’85 or ’83?—to teach school. I was born down in Belen, south of Albuquerque. I grew up right by the railroad tracks. I got a cool teaching job right up here. And I have family from the Santa Fe area, Galisteo area, too. So these are my studios right here.

When I first came to Cordova, I lived in the big house that we were in, the old adobe place. As a schoolteacher, I was the last schoolteacher to live there. And so that family, Josefita and Emilio Cordova were like the Don and Doña of Cordova, and they housed the schoolteachers, real old fashioned–like. I literally was the last schoolteacher to live there, and that was a really sweet experience for me. Later I convinced Terry [Mulert] to come to New Mexico to live here. We’d been married and lived in Europe for a couple years and then came back.

Clayton Porter: Why have you been drawn to metal?

I do a lot of different things, anonymous things, a lot of video. But most people know me as a metal sculptor. I would say it’s really very practical. I grew up with a dad, a grandfather, and a great-grandfather in New Mexico who collected scrap out of need, to make stuff. ‘Cause our world is all stuff, right? I grew up with massive scrap piles around me. A lot of it was metal. A lot of it was wood. I suppose I could’ve gone into wood, but metal is such a great medium, because you can put things together without a lot of force, whereas wood requires a lot of muscle energy, I believe. With metal, all you really need to do is learn how to weld, and tools can really help ease the responsibility of the body. Although, there are things that are required—like lifting things.

Metal carries around with it the histories and all kinds of ways it’s been used before. The other thing about metal and wood, and all the stuff that I grew up around, is the mass. The displacement of stuff on the planet, that’s really intriguing to me. In that way, it’s natural. I think probably some people see metal as sort of in the same genre as marble; bronze is kind of an elite material. I see it, especially the way I grew up with it, as just a lot of discarded stuff that can be regenerated in some way.

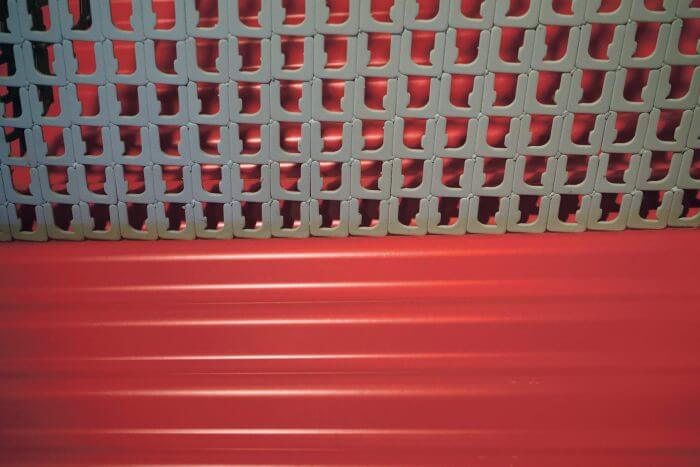

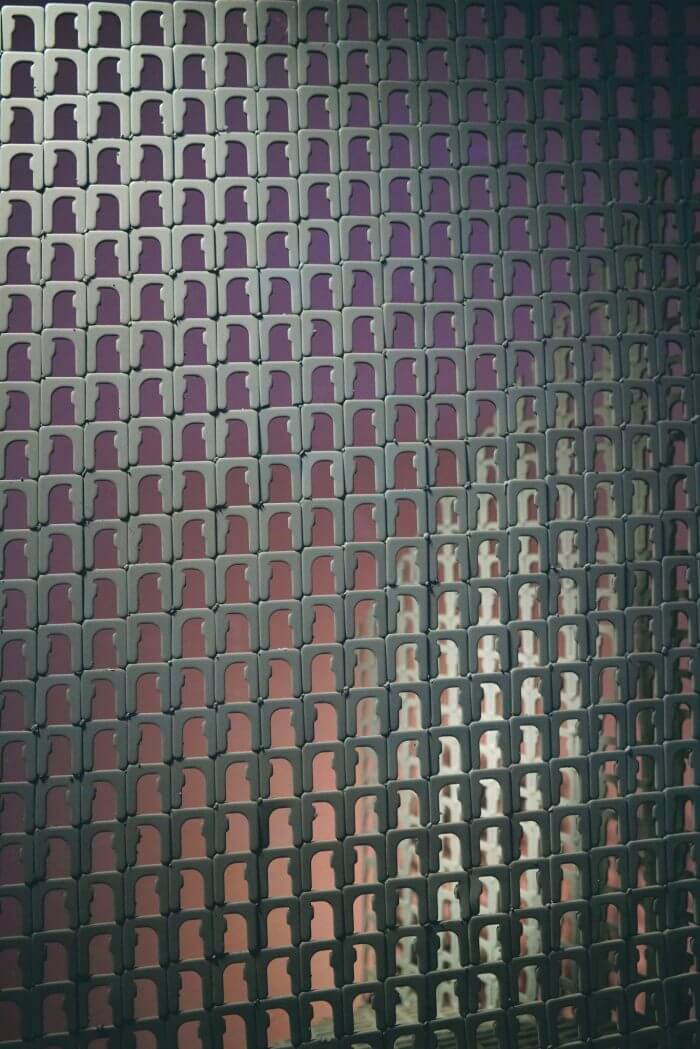

There’s also something about metal and its association with large forces: the Empire. I see metal as the residue of Empire. I experienced it that way because I grew up with the leftovers, I saw it all the time. I also collect it. I use different processes, too, like the piece that was in the [New Mexico Museum of Art, Forrest, (2011-12)], those were all punch-press pieces. I actually got those from a fabricator in Bernalillo, who fabricated all of the casinos in the Southwest over the last fifteen years. And those are leftovers from punching out I-beams for bolt holes. That’s really fascinating, you know? Although that’s definitely a remnant; it reflects Empire in some way—there is something really sort of sad and distorted about that, too. It embodies a doubt in some way, that aspect of leftover-ness.

CP: When did you learn welding?

I grew up with it. My dad was a classic Coloradan guy; you know, rural people know how to do stuff—how to sew, how to weld, that kind of thing. So I was inside with my two sisters, doing the dishes, and my brothers were welding. I was like, “What?!” and eventually, when I was a young adult I just went and bought a little welder. I remember my brother bought me a really nice hood for Christmas, so everyone in my family was really supportive of it. It just didn’t occur to them.

CP: Did your dad give you pointers?

You know, he gave me one pointer, once. My dad’s kind of a funny guy; he has little quips. His little quip is “Don’t marry the damn thing.” Like nothing is that serious; nothing’s that hard. But one time, he looked at my welding, and he said, “You know, you can change the voltage.” That was the only thing he ever said to me. [Laughs.]

LT: You said some of your public work has been anonymous. Why is that?

Because there’s something else that’s more important, maybe. A lot of them are really low-tech pieces. There’s this great piece I did called Letters to Dead Trees [2012-2016]—along Siringo Road in Santa Fe. I was in a particular space, because of certain things happening, and you know how that is—you tend to be much more open to suffering. I was walking around along Siringo, and I started noticing these huge Ponderosas that are used as utility poles, and I was really taken with them. So I started writing letters to them.

CP: Is that part of a practice that’s ongoing?

Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I feel that’s how artists are. I don’t want to exclude anyone else, but I feel like we’re totally voyeurs—almost like picaros, like we live in communities, yet we separate ourselves intellectually, we continue to be able to see things objectively—and thus can critique things. . . in ways that are very gentle and generous.

CP: I see all these easels. There’s been some painting done in here. Where does that fit into your timeline? And how much time did it take for you?

I think when it occurred to me that I wanted to be an artist, I associated being an artist with someone who could paint and draw. A very sort of mythical, fictionalized, what-an-artist-does. I did Kimon Nicolaides’s The Natural Way to Draw. Do you know that book? I did the whole book, taught myself that. Spent some time researching abstract expressionism, how that process worked. Originally, that’s what I thought artists could do. Artists were able to use a lot of different tools to express things. Like a very modernist perspective: you have a studio, you paint, you draw, you sculpt. That’s what you do. So I did that, and it was great. I actually love drawing, and in many ways I feel like drawing resonates with the experience of sculpture, which is sort of bearing witness to things, to material things. Whereas painting still is so wonderful but so elusive and illusory.

At this point, I don’t think it matters. It’s completely irrelevant. It’s like all of these things are available; even the things you’re not good at are available to draw from. And you’ll figure it out—whatever it is you want to communicate, you’ll figure out how to do it. And put things together—I see that as truly contemporary postmodern. The ideas are the things that are really important. ■