It’s artists versus the USSR secret police in Multiple Realities at Phoenix Art Museum, where even the propaganda is sabotaged.

Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s – 1980s

April 17–September 15, 2024

Phoenix Art Museum

I don’t often get goosebumps while viewing art; as a critic I’ve always wished to be more dropped in, less in my head. On the other hand, I struggle to recall a series as twisty and chilling as Gabriele Stötzer’s 1980s portraits of a young transgender woman identified as “Winfried” in Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s – 1980s at Phoenix Art Museum.

The photographs, titled Trans sitzend (Trans Sitting) and made in East Germany in 1983 and ’84, show Winfried rolling on pantyhose, donning a skirt and heels, and buttoning up a blouse. Documenting this gender-affirmative process was a collaborative act of protest in a time of draconian gay policing, but years later, Stötzer learned that Winfried had actually been spying on her for the Stasi, the East German secret police.

“The Stasi took advantage of anyone who was different,” comments Stötzer on the wall label. Cue the full-body shivers as I scanned the photographs again, caught in Winfried’s psychological knot as a surveillant who was doubly surveilled by artist and state. Multiple Realities courses with such Cold War intrigue, featuring nearly 100 artists from Central Eastern Europe who conducted radical art activities while in the political grip of the Soviet Union. The exhibition traveled from the Walker Art Center in Minnesota, where it was curated by Pavel S. Pyś.

Behind the Iron Curtain… performance art was a serious approach to avoiding government censorship.

For the record, Stötzer didn’t need to be shadowed: the artist and avant-garde gallerist was unusually public in her political defiance, which landed her in a USSR prison for a year. While Stötzer sent her version of reality crashing into Soviet society, much of the work in the show is sneakier, leveraging the fracturing forces of authoritarianism to hide subversive messages in the resulting spiderweb of societal cracks.

At the exhibition’s outset, Akademia Ruchu’s 1977 video Potknięcie (Stumble) shows members of the Polish art collective tripping on imaginary objects on a Warsaw sidewalk outside the city’s Communist Party headquarters. The grainy footage catches passersby jumping and double-taking, bringing to mind Candid Camera-style prank videos on YouTube. But behind the Iron Curtain, incorporating invisible bureaucratic obstacles into fleeting performance art was a serious approach to avoiding government censorship.

Official surveillance is a pervasive and oddly mundane force in Multiple Realities. In a 2011–12 archival research project, German artist Simon Menner presents a case of USSR-era found imagery from the now-public Stasi archives. The chaotic snapshots from covert house searches in East Germany are paired with Jan Ságl’s 1973 photo series Domovni prohlídka (House Search), featuring monochrome documentation of his Czech Republic apartment between warrantless police searches that took place while he was gone.

I came away from Ságl’s intimate imagery pondering the pitiably boring mandate of the Czech police. The presence of the photographs proves the investigation’s futility: a friend of the artist successfully concealed them beneath his floorboards and rediscovered them decades later. Even if the police had seized these images, it’s hard to say if their domestic subject matter would’ve raised alarm bells—a masterful wielding of political theorist Elliott Prasse-Freeman’s concept of a furtive “politics of the daily.”

Part of my fascination with Multiple Realities concerns its curatorial backstory; all of these artworks evaded capture in order to land in the show. But stashing entire bodies of work in hopes that society may finally open up is a safe but surely unsatisfying strategy for politically oriented artists. Some of the finest creative espionage in the show instead involves hiding messages in plain sight.

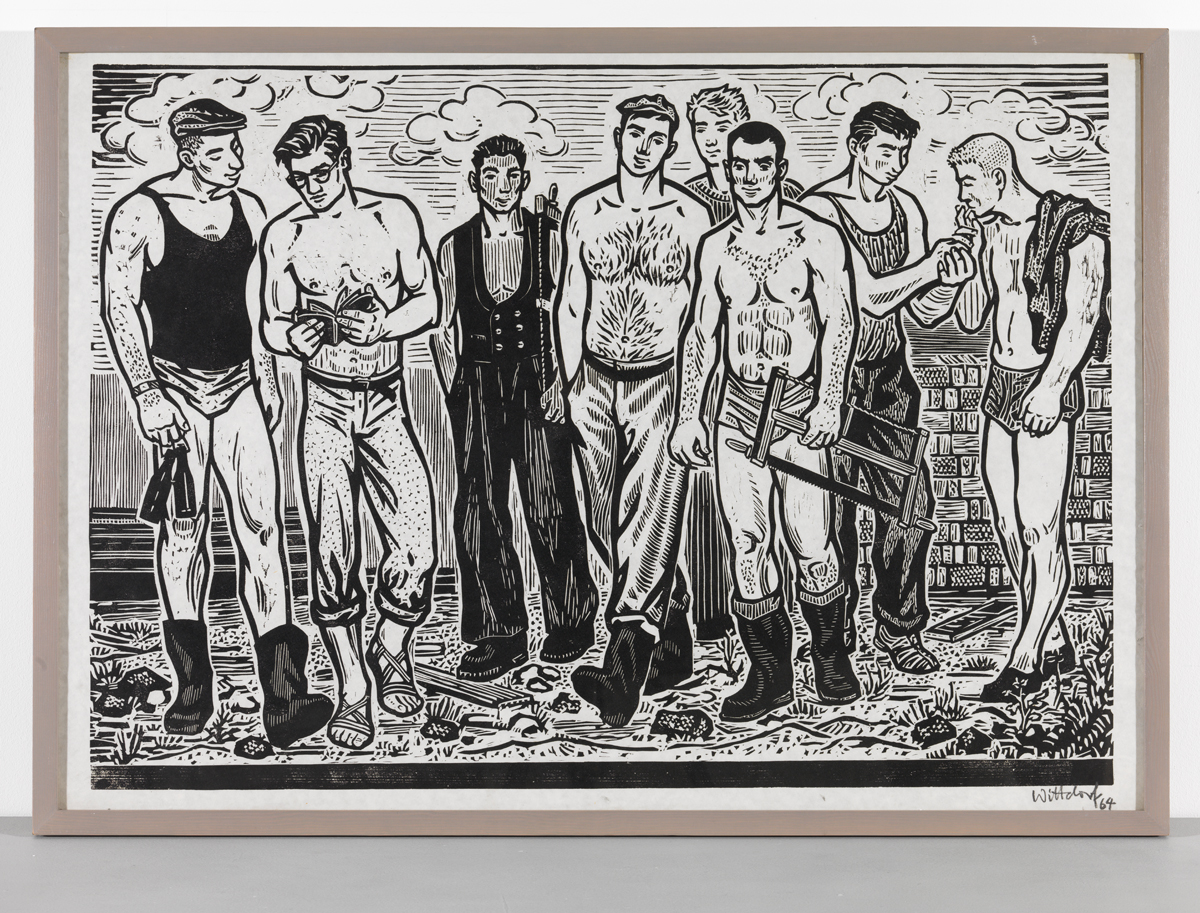

Jürgen Wittdorf, a printmaker who only embraced his gay identity after Germany’s reunification, infused Soviet-commissioned 1964 linocuts of muscular athletes with aching homoeroticism. (A steamy group shower scene surpasses the “gay utopia” of Russian-Chinese friendship motifs in other Communist propaganda.)

[In Multiple Realities], I found dozens of underground party scenes made brighter and more effusive by their reactionary origins.

Fiber artists from Poland used the under-the-radar Lausanne Tapestry Biennial in Switzerland, which ran from 1962 to 1995 and accepted Soviet artists due to its host nation’s neutrality, to exhibit radically experimental (though mostly abstract) tapestries—and communicate with contacts in Western Europe.

Other exuberantly subversive activities in Multiple Realities include radio broadcasts, jazz concerts, nude outdoor recreation, table tennis matches, and dance parties. I have to admit that, before entering the show, I imagined slogging through the muddy palette of Socialist Realism. Instead, I found dozens of underground party scenes made brighter and more effusive by their reactionary origins.

By the time Multiple Realities spit me out, the show’s title seemed like a subtle misnomer. An authoritarian environment does produce layers of reality, but as Stötzer loudly pointed out, they’re as laminated as a Russian Napoleon cake. The art rave hiding at the bottom is inevitably informed by the repression and violence at the top—and vice versa.