The recent destruction of Santa Fe’s Multicultural mural caused fierce controversy, but its little-told history reveals tough questions about authorship and cross-cultural collaboration.

SANTA FE, NM—More than forty years ago and under a blistering summer sun, ten artist-volunteers labored to finish an artwork—which would cause decades of controversy before ultimately meeting its demise—on the side of Santa Fe’s State Records and Archives building.

The dedication ceremony for the Multicultural mural was in late September of 1980. Some of the contributors were in attendance, but the project’s official lead artist, Gilberto Guzmán, was notably absent.

Instead, a lanky white woman with a thick German accent took the microphone. Her name was Zara Kriegstein, the project director for the Multicultural mural, and she’d spoken extensively to the press about the artwork as it took shape.

“The mural is about the values of the people of the different cultures, the values the people are living with,” she told the Santa Fe New Mexican three months previously. “And perhaps it is a reminder of the dangers to those values if we are not careful that they are not destroyed.”

She was referring to a long-dominant notion of New Mexico’s tri-cultural heritage that informed the project’s structure: “The Indian, the Spanish, and the Anglo. There are two artists from each culture working on the mural,” Kriegstein explained.

The Multicultural mural no longer exists; the building it adorned is slowly transforming into Vladem Contemporary, a freestanding wing of the New Mexico Museum of Art that will house its contemporary collection. The mural’s fate was the subject of fierce debate and protest in the years preceding the construction project.

Kriegstein’s story reveals a subtle and tense thread of Santa Fe’s recent art history that was eclipsed by the uproar. Despite the project’s intersectional premise, Guzmán received credit and funding for the Multicultural mural while his collaborators were reduced to footnotes—mere “assistants,” as he later dubbed them.

Simmering animosity between Guzmán and the other artists exploded in the early 1990s, when Guzmán accepted a major grant to rework the mural’s aesthetic. “I just feel it was unfair,” Kriegstein told the press at the time. “Ten people worked four months, [and] now one person goes, ‘I did it, it’s my mural and I get the money.’”

There was not one master with the rest of the people filling in the squares,” Kriegstein told the Santa Fe New Mexican just before the mural’s unveiling. “The best use of the talents of the multicultural artists was crucial.

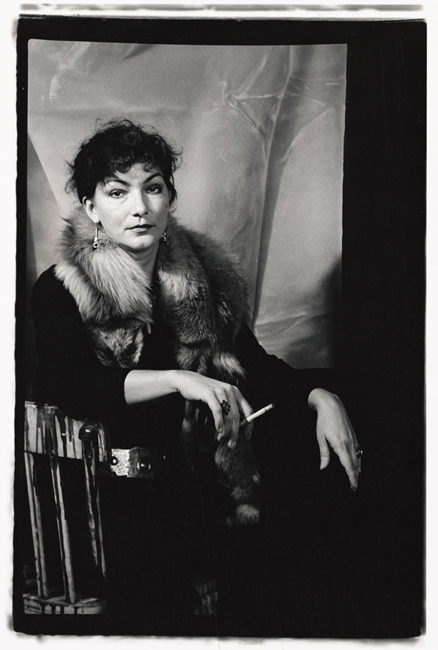

Kriegstein passed away from liver disease in 2009 at the age of fifty-seven. She’d spent the majority of her life in Santa Fe, far from her birthplace of West Berlin. Aline Hunziker, an artist who grew up in Santa Fe with Kriegstein’s late son Gandalf Gavan, worked intermittently as Kriegstein’s assistant and helped care for her in her final years.

“She would float into the room on a cloud, with emerald green eye makeup and a cigarette holder and her parrot, Loretta,” Hunziker says. “She’s the only person I ever knew in the whole wide world who could call anyone ‘darling’ and it was completely natural.”

Early in her time in Santa Fe, Kriegstein conducted some curatorial work, teaming with renowned painter Eli Levin to open the Realist Gallery in Burro Alley. The space showcased numerous local artists in its six-month run, and though it ultimately lost $12,000, Levin remembered Kriegstein fondly.

In her obituary in the New Mexican, he recalled his first encounter with Kriegstein. “She looked like a Russian countess,” Levin said. “She had a mink or some kind of animal fur thing with the head and everything… I was just blown away. I hadn’t seen such a good artist and such a fancy-looking lady all at once.”

Before moving to New Mexico in 1977, Kriegstein lived in London and was involved with an art gallery that had ties to New Mexico’s Synergia Ranch. According to family members, the mysterious intentional community likely drew Kriegstein to New Mexico, where she would meet Guzmán.

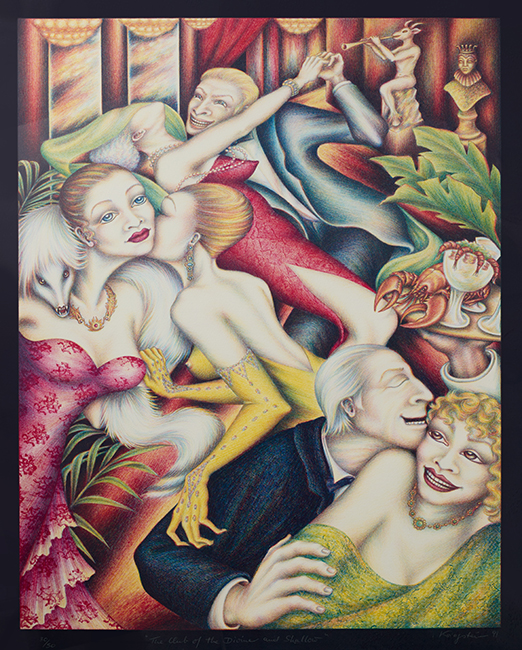

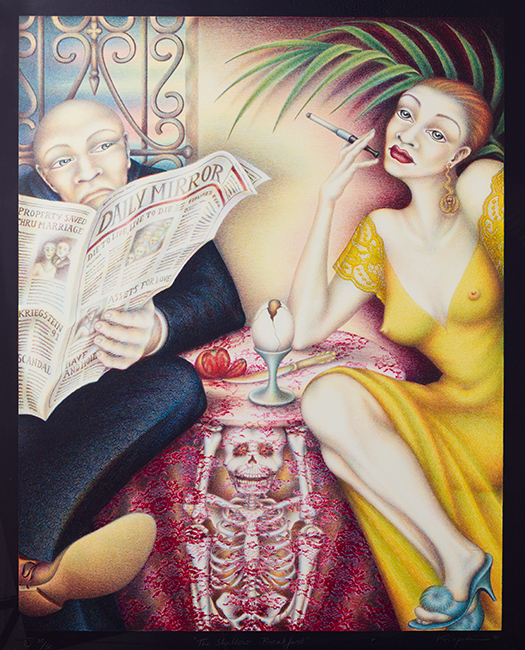

Guzmán was from eastern Los Angeles, and moved to Santa Fe in 1971. He was gaining international notoriety for a vibrant, rounded style inspired by Mexican modernism. His aesthetic corresponded in compelling ways with that of Kriegstein, who combined German expressionist and Mexican muralist influences in her paintings. Her subject matter blended sharp social realist critique with the restless wonder of futurism and magical realism.

“There was a line of history there that you could see in her work, when you think about who was coming around Europe in the decades before that—Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera and all of those artists,” says Willy Bo Richardson, a Santa Fe-based painter who was another friend of Kriegstein’s son.

While she was in London, Kriegstein tapped her art world connections to land Guzmán a mural commission in the counterculture enclave of Camden Town. Kriegstein and Guzmán envisioned the Multicultural mural as an answer to that piece—an “international gift,” as Kriegstein called it in the press.

Despite the project’s transatlantic origins, the Santa Fe transplants settled on a hyperlocal premise for its content and execution. They engaged local artists of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds to depict New Mexico’s past, present, and future.

“There was not one master with the rest of the people filling in the squares,” Kriegstein told the New Mexican just before the mural’s unveiling. “The best use of the talents of the multicultural artists was crucial.” She and Guzmán made the master sketch for the mural, but according to contemporaneous accounts from Kriegstein and other participating artists, everyone contributed to the massive composition.

Guzmán conceived of several major elements of the mural, such as a bull and a Corn Mother figure, while Kriegstein designed the fiesta scene at the mural’s heart and worked with David Bradley (Minnesota Chippewa) to depict the Rio Grande Gorge.

Bradley also composed an eagle and a snake, Frederico Vigil designed a tree, and Rosemary Stearns painted a desert expanse. (“This is the biggest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Stearns told the New Mexican.) Cassandra Mains also added elements, and Linda Lomahoftewa (Hopi and Choctaw) engaged student helpers from her introductory painting class at the Institute of American Indian Arts.

This utopian vision of the mural’s creation, perhaps stoked by Kriegstein’s short-lived involvement with the Synergia Ranch, belied serious tensions that would eventually burst into public view.

Throughout the painting process, passersby critiqued the Multicultural mural’s aesthetic, and the New Mexican published letters from readers arguing over its “political” nature. Guzmán skipped the mural’s debut due to conflicts with the rest of the team, but his estranged wife, Antonia Padilla Guzmán, appeared at the event and accused Kriegstein of pushing other artists out of the spotlight.

In an impromptu speech at the event, which earned its own headline in the New Mexican, Padilla Guzmán railed against “outsiders” and “foreigners” who were “imposing their artistic preferences on the Native people of New Mexico.” She accused Kriegstein of accepting funding for the mural from a “cult,” a claim that the New Mexican was unable to confirm.

Then, in 1993, Guzmán received a $40,000 grant from Absolut Vodka to single-handedly paint a fresco over the original mural, preserving the basic composition but significantly altering its aesthetic. Stearns expressed support for the update, but the idea infuriated several other artists who had contributed to the design.

“I haven’t been approached or talked to,” Vigil told the New Mexican at the time. “I think the way it’s being approached is very selfish.” Guzmán’s response was frigid: “They were just assistants. They have no rights to it. I told them if they have any problems, to take me to court and talk to my attorney.”

Nevertheless, Guzmán was the only artist named on the original contract with the State of New Mexico, and he eventually proceeded with his plans. Part of the intention, he explained to the press at the time, was to create a version of the mural that would withstand the elements better.

But Guzmán also critiqued the earlier work’s content in the press at the time, calling it “hodge-podge” with “work by too many hands.” “Maybe the group working on the mural was a multi-cultural group… but the mural doesn’t represent that to me,” he said.

They were just assistants,” Guzmán told the press. “They have no rights to it. I told them if they have any problems, to take me to court and talk to my attorney.

Kriegstein fired back, claiming that although the original mural had some conservation issues, she couldn’t fix it without Guzmán’s cooperation. “Simply, legally, we couldn’t just go and restore it,” she said.

The recent controversy surrounding the mural’s erasure carries curious echoes of this earlier conflict. In the decades following its creation, the work had become a local symbol of Chicano and Indigenous pride. When the New Mexico Museum of Art presented plans to stucco over the mural, claiming that it hadn’t been maintained and wouldn’t survive the renovation, Guzmán joined local activists to protest its destruction.

Last September, Guzmán struck a $42,000 deal with the State of New Mexico, comprising settlement money and a commission fee to paint a smaller version of the mural that is scheduled to appear on panels inside the museum.

As for Kriegstein, the Multicultural mural was a rocky start to a reliably community-oriented art career in Santa Fe.

“Zara felt that [the mural] had really departed from the original vision, which was one of many voices—of multiplicity and shared authorship,” says Nicola López, a Brooklyn-based artist who grew up in Santa Fe and is the widow of Kriegstein’s son Gavan. “But I don’t think it was a source of deep, ongoing resentment.”

Kriegstein’s subsequent projects were also designed to engage with the state’s complex history and multifaceted community. Most notably, she collaborated with David Pratt on a mural of Zozobra that’s still visible along Cerrillos Road, and received a $40,000 commission to create a series of large-scale paintings for Santa Fe’s Municipal Court on Camino Entrada.

During the latter project, which unfolded in 1995, Kriegstein invited contemporary Santa Feans to sit for portraits and wove their faces into scenes from New Mexico history. Other major projects included a mural called The History of Jazz and Blues at a contemporary art museum in New Orleans, and a portrait commission for the rock and roll pianist Jerry Lee Lewis.

In addition, Kriegstein taught dynamic art classes as a guest instructor at Santa Fe Preparatory School, recalls Richardson.

[Kriegstein] looked like a Russian countess,” recalled Eli Levin. “I hadn’t seen such a good artist and such a fancy-looking lady all at once.

“She was wild,” he says. “Skinny and smoking and glamorous, and swearing in that German accent. She didn’t know anything about school etiquette, but she was the first person to teach me acrylics.”

For most of her time in New Mexico, Kriegstein owned a Santa Fe home with a lush greenhouse for a front entryway and a hand-embroidered flag of Vladimir Lenin on the wall. She lived there for many years with her husband Felipe Cabeza de Vaca, who helped with the Multicultural mural and called her his “partner in life” despite their eventual divorce.

“We got together and started shaking things up a little in Santa Fe,” Cabeza de Vaca said in Kriegstein’s obituary. “Every time we tried to do [a mural], we were defacing another wall.” His requiem is both reverent and loaded, acknowledging Kriegstein’s indelible mark on Santa Fe’s urban landscape—and the controversy that engulfed it.

López says, “I wonder what Zara’s contribution would be in this moment, when conversations about cultural participation are so different. The spirit in which this mural was undertaken resonates with very important conversations that are happening now. These are not easy conversations and they don’t all go down smoothly—and they probably shouldn’t. But it’s an occasion for thinking about what community means.”

Correction 6/13/2022: An earlier version of this story stated that Gilberto Guzmán received a $42,000 settlement and commission fee from the City of Santa Fe, not the State of New Mexico.