Eco art is attracting a new generation of artists, but when working with the land, there’s a way to do it right and a way to do it wrong.

The history of the separation of art from the natural world is older than the history of the separation of art from the world of reason, but this breach, too, has had a staggering effect on how humans grapple with their fate.

— Barry Lopez, Horizon, 2019

Indeed, this is perhaps the most important question ever to confront culture in the broadest sense— for let us make no mistake: the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.

—Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 2019

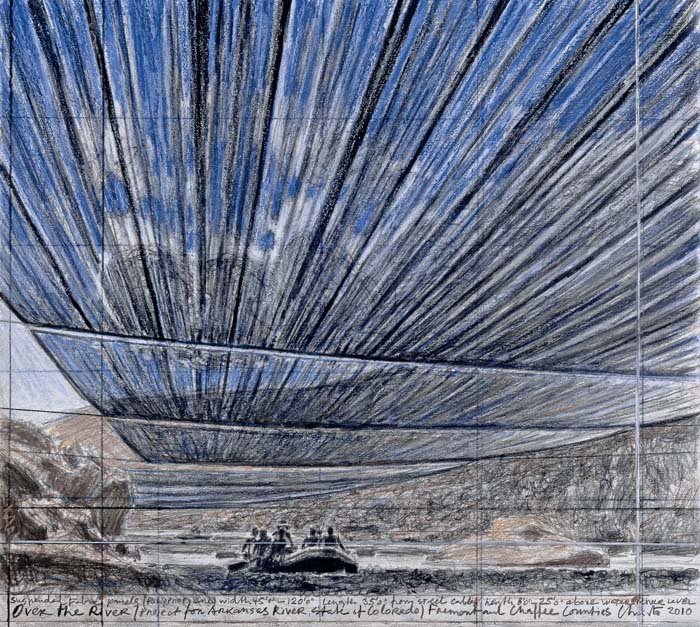

For more than twenty years, artist duo Christo and Jeanne-Claude tried to convince the people of Colorado to allow a spectacular intervention over the Arkansas River from Cañon City to Salida. The installation of transparent, shimmering, silver panels stretched over the river—an ephemeral imposition on the landscape, a mere impression, in typical Christo and Jeanne-Claude fashion—would last only two weeks before being dismantled.

The artists commissioned extensive environmental impact reports and reviews, and in 2011, the project secured approval from the Bureau of Land Management. Construction on the project, however, was delayed by lawsuits and appeals filed by a local group of environmental activists and concerned citizens. They claimed Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Over The River project would adversely affect sensitive animal populations, such as bighorn sheep and bald eagles, choke traffic during construction with heavy machinery, and mar the landscape.

The opposition was not only environmentally driven, but also couched in aesthetic terms— they called themselves Rags Over the Arkansas River, defying Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s definition of beauty, and their claim of the primacy of art. While Christo and Jeanne-Claude were no strangers to lawsuits and bureaucratic delays to their ambitious public art projects—in fact viewing these proceedings as integral to their art process—the campaign ROAR waged against Over The River was well-publicized, relentless, and fierce. A spokesperson for ROAR likened it to a battle between David and Goliath.

In January 2017, while still awaiting a decision from a federal appellate court, Christo, then eighty-one years old (Jeanne-Claude died in 2009), announced that he would no longer pursue Over The River. The reasoning behind the decision, he stated, was a refusal to engage with the incoming Trump administration, as the project would have taken place on federal lands. Whatever the reason, the environmentalists rejoiced.

Christo, who died in 2020, and Jeanne-Claude had realized many large-scale artworks in the environment, and described themselves as “environmental artists.” Yet they often found themselves at odds with environmentalists over what were essentially massive construction projects.

But what is environmental art? Is it art on an environmental scale, à la Christo? Or art that is for the environment, taking up the banner of environmentalism as a cause?

In considering environmental art as a medium, does the land and the surrounding environment itself serve as canvas, as support, as a mere surface?

That view becomes complicated by the recognition of not only the environment—or what surrounds us—but the ecology, as in the interrelationships and interconnectedness between us and the environment.

Interventions in the landscape have a long history, as long as human history. Land Art, as a genre of contemporary art, can be considered about fifty years old, a precursor to environmental art, which encompasses a range of artistic disciplines, from monumental earthworks to ecological art projects that engage with the specific ecological systems of a site. Emphasis differs between transformation and restoration, spectacle and storytelling. Intention is weighed against impact.

I suspect the bulldozer-driven interventions of Land Artists of the 1960s and ’70s wouldn’t fly today among a crowd concerned with environmental justice (though Michael Heizer would try to prove me wrong). Even ephemeral anti–Land Art actions like Judy Chicago’s Atmospheres (various iterations from 1968 to present), which “soften” a landscape with colored smoke, give environmentalists a headache. The naysayers who frown at hikers on Instagram for stacking unnecessary rock cairns might even have something to say to Ugo Rondinone and his Seven Magic Mountains (2016). But I might be getting a bit cynical here.

I asked eco art scholar and Southwest Contemporary contributor Paige Hirschey to disentangle environmental art and eco art. In the ’90s, as art historians looked back at Land Art, she says, “There’s a distinction drawn between artists working in the land and artists specifically concerned with the climate crisis. If you’re going to be making art that’s about protecting the environment, you shouldn’t be contributing to environ- mental degradation.”

In the Over The River project, she points out, “They’re using the earth as a canvas; the earth is just this neutral background.” The land served as the support for the art, but the project was more about enjoying nature, rather than saving it. “It wasn’t intended to disturb the landscape, but it also wasn’t going to protect it.”

In the early ’90s, when eco-conscious art was in its nascent stages, Patricia Lea Watts was building a library of research on “art in nature.” Watts conceived of ecoartspace in 1997 and published one of the first websites with a directory of artists addressing environ- mental issues. The idea of working for nature rather than in nature was relatively new. “There wasn’t even a conversation yet,” she says, recalling early efforts at fundraising and “introducing this movement.” In the ’90s, she says, artists were starting to collaborate with scientists on ecological restoration projects. “We knew about Land Art and Earth Art, which was still kind of a memory at that point,” she says, but the artists she was most interested in were working on more intangible objects.

After 2001, the field of social practice expanded, she recalls, as artists focused not only on large projects but also on small individual actions. “By 2010, [there were] more and more shows, and [eco art] just exploded,” she claims. Since 1999, Watts and her collaborator, East Coast–based Amy Lipton, who passed away in 2020, have worked with hundreds of artists.

“Ecoartspace has always been what I call a ‘platform,’” Watts says, adding that she and Lipton had created it as a springboard for their independent curatorial practices. In 2020, ecoartspace shifted to a subscription membership model. Today, the ecoartspace community has around 800 active members from around the world—including artists, curators, art professionals, galleries, institutions, students, and scientists. “I want [ecoartspace] to be open,” says Watts, who moved to Santa Fe from California in 2019. “If any artists are interested in this work… I want them to get the resources they need, to be inspired, to up their game, and their practice.”

Academic specialization in art and ecology has grown as well. The Center for Art + Environment, a research library and archive at the Nevada Museum of Art, was founded in 2009, the same year the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque began offering degrees in Art and Ecology. (Many others have recently followed suit. Among them, Goldsmiths, an influential art college in London with an avant-garde reputation, started offering its MA in Art and Ecology in 2021.)

Art and environment–geared artist residencies abound as well, from established art and ecology projects to off-the-grid sustainable living experiments. I recently visited University of Colorado Boulder students at the end of a three-week Art and Environment Field School that took place in the Rocky Mountains. We were up at CU’s Mountain Research Station, which hosts research scientists year-round and, sometimes, artists. The MRS is also the site of one of the world’s longest-running atmospheric CO2 measuring experiments.

One of the artists, Daphne Talusani— majoring in environmental studies with minors in art and ecology and evolutionary biology, or ebio—brought us up to an overlook on a steep hillside. A child-size wooden coffin lay open on the slope below, containing a single aspen branch. The artist delivered a eulogy for the aspen branch, warning of Western culture’s obsession with preservation and legacy.

There can be a gap in understanding when artists translate scientific research into aesthetic gestures.

As we walked the grounds to each site, a few visitors arrived to see the artists’ works between scant rain showers. The resident scientists, however, gathered around a propane fire ring outside one of the resident halls and stayed aloof.

Artist Aaron Treher, the instructor leading the program, has regularly collaborated with scientists, which he describes as a “give and take” relationship. “It broadens your understanding of the work itself,” he says of the insight and focused experience scientists provide.

There can be a gap in understanding, however, when artists translate scientific research into aesthetic gestures. Treher related a story about an art project he staged as an artist in residence at the MRS, where he flooded one of the rustic cabins on-site with the light from three mercury vapor lamps—old-school street lights with a blue-green tint—to see how many moths and bugs would gather inside. While most of the researchers were interested, one came in, looked around in irritation, and demanded, “What the heck are you doing?”

Treher’s work hinges on a kind of collaboration with animal species—particularly barn swallows, an animal whose evolution is uniquely intertwined with human architecture. His work with evolutionary ecologist Rebecca J. Safran, who has studied barn swallows for twenty years, informs the art and ensures the birds’ safety. “I do see myself as helping create habitat and doing things that are beneficial,” he says of the structures he creates for barn swallows, “but there’s a way to do it right and a way to do it wrong.”

Inspiring the next generation of artists, artist and educator Carol Flueckiger incorporates drawing assignments about sustainability and ecology into her pedagogy at Texas Tech University in Lubbock.

“We practice drawing continuous line,” she says, giving an example of a lesson where students draw while looking at their subject, not at the paper, and without lifting their pencils. “It’s a beautiful metaphor,” she continues, “because we can talk about interconnection of the ecosystem.” Lessons on figure-ground reversal and negative space lead into conversations about natural resources and atmosphere, and questions of value. “Culturally, we don’t value the [negative] space between our body and the wall, and that’s why we’re in trouble with our environment,” she emphasizes. “It’s a formal and a metaphorical conversation.”

Flueckiger runs a summer Art, Environment, and Sustainability Residency in Paonia, Colorado, with Elsewhere Studios. MFA students from Texas Tech and environmental management majors from Western Colorado University in Gunnison gather to open up possibilities of collaboration and interdisciplinary cross-pollination.

This summer, Flueckiger added a new program for art undergrads to work with Ogallala Commons, a nonprofit organization committed to the health of the Ogallala Aquifer and the communities that depend on it. The Commons brings together a wide range of community members and disparate stakeholders—ecologists and ranchers, artists and farmers—to encourage sustainable stewardship of the land. Rural West Texans are not known for their progressive politics or eco-consciousness, but they are witnessing their wells starting to run dry. Flueckiger hopes that by exposing young artists to bioregional ecological concerns early on—as undergrads—their art will engage with place and environment, and open dialogues locally to effect positive change.

For Watts, opening conversations about the health of the environment is a vital part of the work eco artists should be doing. “We want to have artists out there having these conversations in all types of communities, not just the art community. I think the more, the better,” she says. “In the middle of the pandemic, my phrase was always, ‘All hands on deck.’ As many of you out there as possible, in as many places as possible, doing this work.”

As the Anthropocene wears on, artistic interventions—even on an environmental scale—start to look quaint in the face of hyperobjects like climate change.

“In the mainstream view of the ’90s and early 2000s, [the climate crisis] was seen as one issue among many others,” Hirschey says. “Now you can’t talk about the climate crisis without talking about capitalism and patriarchy and colonialism. These things are all intertwined, and I think we didn’t have that realization twenty years ago. Eco artists are responding to that by having these much more conceptual, more expansive projects. It’s more about changing the way we relate to the earth.”

The earth is not a neutral backdrop. It does not serve as a mere support for the art but, rather, is recognized as the support for all life.

“We’re all just watching the world around us change so much and disappear and be on fire,” artist Kaitlin Bryson tells me. The increasing number of artists working in an ecocritical way, she says, “feels like a growing response to what we’re all witnessing.”

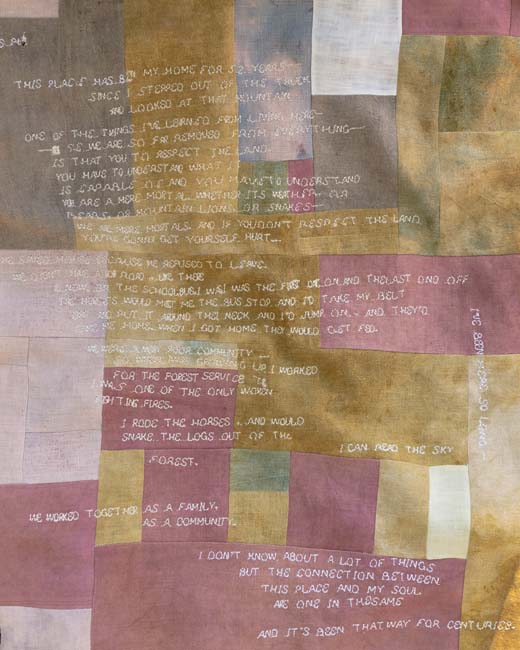

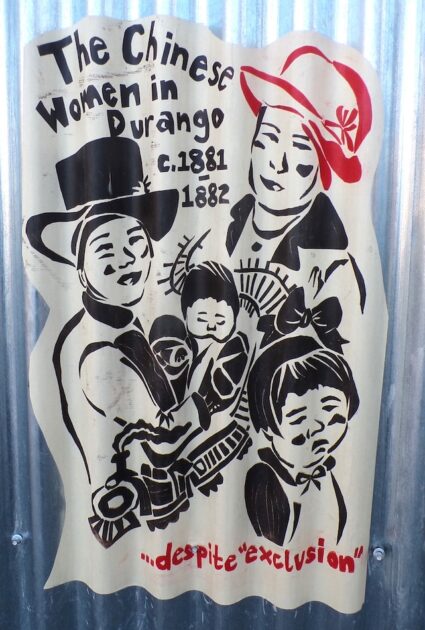

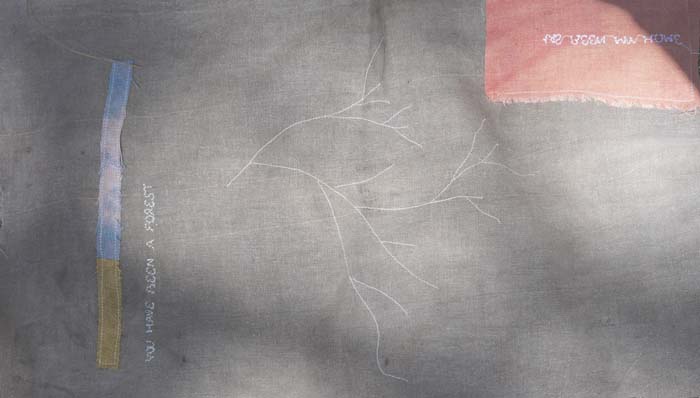

Bryson, a UNM Art and Ecology alum and ecoartspace member (and one of Southwest Contemporary’s 2023 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now), recently announced the launch of the project Bellow Forth, funded by a $20,000 Anonymous Was a Woman Environmental Art Grant. The project—situated in the lands of Northern New Mexico devastated by the 2022 Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak wildfire—is deeply complex. It reflects a realization of the interconnectedness of climate, community, the effects of colonization, the loss of Indigenous caretaking and knowledge, and local ecology.

There is no great spectacle, no grand environmental intervention upon the landscape. The aesthetic gesture—quilts stitched with memories shared by the communities affected by the wildfires—will be buried in the ground. The quilts are intended to “restory” the soil, having been “inoculated with nutrients to attract native fungi and microbes who are essential for soil and land regeneration.”

Bellow Forth comprises invisible impacts: deep listening, the transmission of stories, the outpouring of grief, acts of mutual aid, reciprocal restoration, and the repair of vital microbial and fungal communities within the very earth. The earth is not a neutral backdrop. It does not serve as a mere support for the art but, rather, is recognized as the support for all life.

Watts, who served on the jury for the grant, likens the project to the visionary ecological restoration projects eco artists embarked on in the ’90s—in collaboration with scientists but with more focus on community, social practice, and solutions.

Bryson calls it an ecologically relational artwork that aims to shift the rhetoric and the expectations of artists and artwork in the environment, engaging more-than-human audiences. “Maybe these things are not spectacular for human eyes,” she suggests, “but maybe they’re spectacular in the way that they create community, generate multicultures, multispecies relationships, and foster soil health and resiliency for those places.” The work resides in the relationships built—the art object is sub- merged into the earth, challenging what art can be and what it could look like.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art was driven by spectacle, by art for art’s sake, but it had a radical seed: its emphasis on community engagement, predecessors to social practice as a discipline. The bureaucratic process, the community meetings, the environmental impact reports, all of that was a crucial aspect of the art.

In a way, the Over the River project may have galvanized members of the community to think differently about their landscape, and to unite against incursions in it. Perhaps such outcry could be translated into resistance against the kinds of extractive industries that disrupt and pollute the environment. If you can fight Big Art, can you fight Big Oil and Big Gas?

Bellow Forth, in its emphasis on the communal, in its investigation of many interconnected threads and ecological complexities, stands in contrast to art interventions like Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s, which privilege art over the environment. “That art world is going to do that,” says Watts, “and the rest of us are out here doing the harder work, problem-solving in an even deeper way that’s probably going to be more profound, and do the work right.”