Reflecting on Weather Report: Art and Climate Change, Lucy Lippard’s 2007 exhibition at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Paige Hirschey discusses how the field of eco art has changed.

This article is part of our Finding Water in the West series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 7.

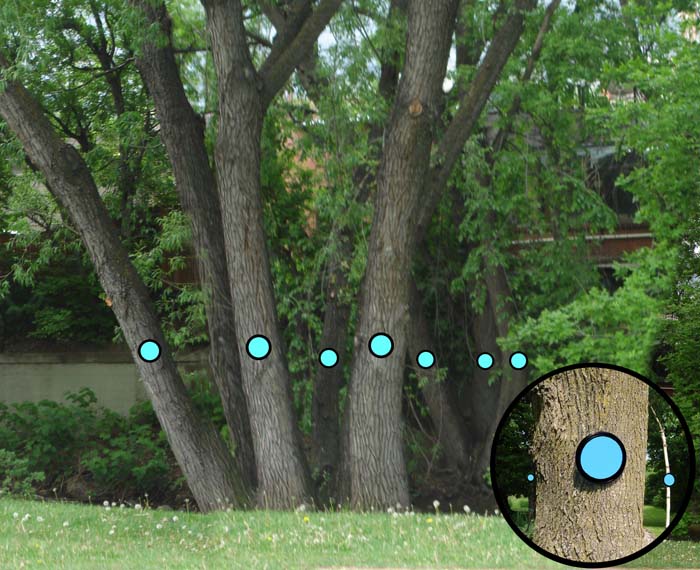

As part of the 2007 exhibition Weather Report: Art and Climate Change, curated by Lucy Lippard at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art and conceptualized by EcoArts Connections, Mary Miss affixed vibrant blue discs to trees and buildings in the area surrounding Boulder Creek, their placement indicating the water level that would most likely be reached during the next 500-year flood.

I have only vague memories of the show—I was fifteen at the time—but I remember encountering the blue dots hung at chest height on the door to my high school, not that I was wholly surprised by the warning they conveyed. Growing up in Boulder, the threat of a flood like the one that reshaped the city’s geography in 1894 loomed over our heads like an environmental ghost story, a constant but seemingly hollow threat.

Just six years after the BMoCA show, Miss’s estimates proved to be all too accurate when Boulder County received a year’s worth of precipitation in forty-eight hours—a coincidence, if one could call it that, that Lippard has marveled at in recent years. The city has since recovered, but at the time it felt nothing short of apocalyptic; my atheist mother repeatedly described the deluge as “biblical.” Mountain roads were wiped out, dozens of homes were destroyed, and neighbors were bewildered to find dead fish in their yards in the days and weeks that followed.

Looking back now, on the show and its aftermath, it seems like an apt parable for our time. The existential threat posed by global warming is a distant specter, one that we need an artist’s help to even imagine until, all at once, it isn’t.

As we collectively experience more (supposedly) once-in-a-lifetime weather events—Australian bushfires, extreme droughts across east Africa, historic heat waves in India, Europe, and the Middle East, hurricanes Harvey, Maria, and Sandy, and, closer to home, the Marshall fire, the most destructive in Colorado history—it is becoming increasingly clear that the climate emergency is no longer a looming threat to be dealt with by future generations, it is a reality to which we must adapt.

When Weather Report was exhibited in 2007, environmentalism still felt like a relatively niche, or at least self-contained, issue. This was the era of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, rampant climate denialism, and widespread American indifference to Bush’s withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol.

In the years that have elapsed, climate anxiety has become a part of the intellectual ether. Every day Timothy Morton’s suggestion that it is no longer possible to have a simple conversation about the weather rings more true.

The climate has gone from the background to the foreground of our lives, and the statistics bear this out. According to Pew researchers, American concern for the environment has increased significantly over the past two decades, especially (and predictably) among young people and liberals, though even conservatives are now more likely than not to attribute extreme weather within their community to global warming.

This shift in consciousness is reflected in the eco art that has been produced over the past fifteen years. Mary Mattingly’s installation Last Library (2020), an ongoing project developed during her residency at the University of Colorado Art Museum, combines books, artworks, and scientific samples to help visitors imagine “ecotopian” futures. Marguerite Humeau’s earthwork Orisons, set to open this summer in the San Luis Valley, will create an “opera” that amplifies and celebrates the “presence of all living, decaying, dead, or dormant beings on the site” as well as its spiritual and mythological histories.

On their surface, these works may not seem all that different from the art displayed in Weather Report, and I would even contend that their core objective remains largely the same: to give life to the detached language of environmental science and imagine ways to resist the status quo.

But as our relationship to the planet changes, artistic strategies of resistance are necessarily evolving. Eco artists working today seem to share a recognition that the climate crisis demands not only fixes to existing systems, but a wholesale change in values. This has precipitated a shift in perspective in terms of what eco art can and should do, from raising the alarm to reaffirming our connection to our planet and the biota with whom we share it, from outlining the horrors of global warming and casting aspersions on its worst culprits to imagining ways to exist together.

There is still a monumental task ahead of us, but if the eco artist’s role before was to “open our eyes,” today it is to teach us how to live with our new knowledge and, in doing so, hopefully change our future.