Horizons: Weaving Between the Lines with Diné Textiles at MIAC pairs historical and contemporary weaving with photography and other media to create connections across materials, time, and lands.

Horizons: Weaving Between the Lines with Diné Textiles is an exhibition created “by weavers, for weavers,” as curator Hadley Jensen puts it. Jensen and Rapheal Begay (Diné) curated the show for the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe. The exhibition features more than two dozen weavings, photographs, and digital designs.

The exhibition originates from another that Begay and Jensen collaborated on earlier this year, Shaped by the Loom: Weaving Worlds in the American Southwest at the Bard Graduate Center in New York City. A showcase of the American Museum of Natural History’s collection of Indigenous weavings curated by Jensen, Shaped by the Loom aimed to share the “ecosystem of craft production in the Southwest.” While neither Shaped by the Loom nor Horizons is meant to be an exhaustive survey, Jensen, while working on the first show, recognized the need for more exhibitions to rethink historical collections while creating new connections between past and contemporary works.

“We wanted to find new ways to think across media, inviting viewers to engage with art and objects differently while deepening the collaboration we already had,” Jensen explains. And so Horizons began to take shape and became even more profoundly cooperative. Horizons is the result not just of Jensen and Begay’s curatorial work, but that of an advisory committee of five Diné artists and scholars, including Lynda Teller Pete, Kevin Aspaas, Larissa Nez, Tyrrell Tapaha, and Darby Raymond-Overstreet.

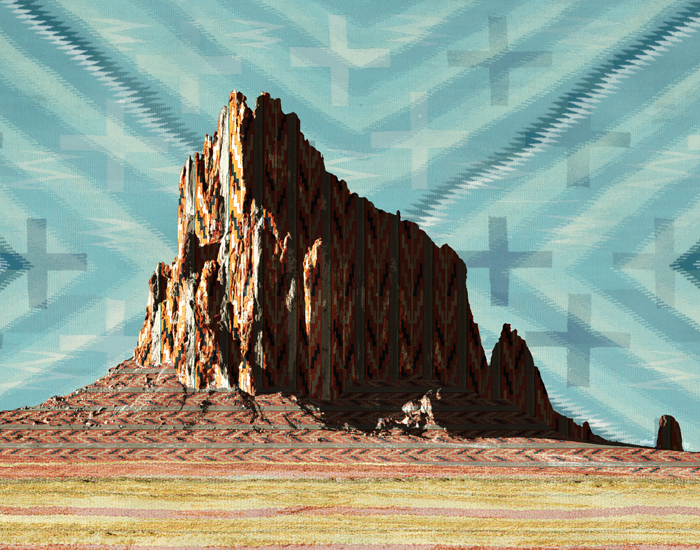

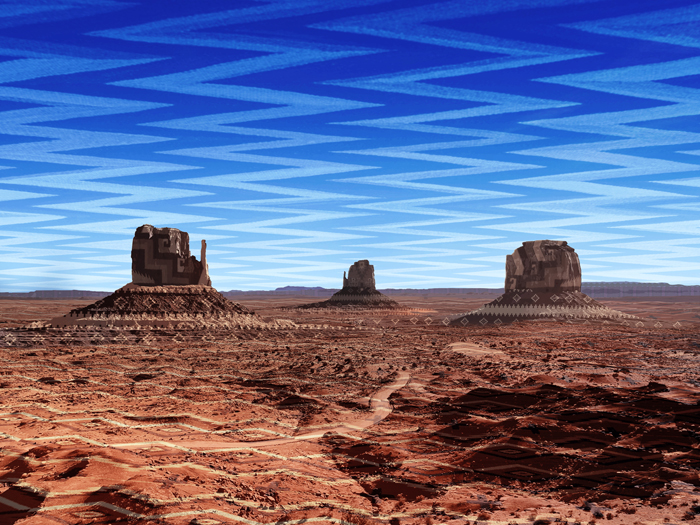

“Horizons was first and foremost about advancing a collaborative methodology when it comes to exhibition making, as well as placing weaving and photography in dialogue as two ways of knowing and engaging with place,” Jensen says. To that end, the exhibition features a range of textiles, as well as photography by Begay, and other work, including a series of “woven landscapes” by Raymond-Overstreet that combine photography with digital printmaking and the language of Diné design to “visualize this way of knowing in a really innovative way,” as Jensen says.

“To some, the combination of weaving and photography may seem like an unlikely pairing,” Jensen continues. “But for Rapheal and I, it was powerful to consider how both of these media articulate relationship to place in different ways.” In the process of organizing Horizons, Jensen learned a lot about what that looks like, and the exhibition reflects a tremendous variety of perspectives, concepts, and approaches to both textiles and the idea of place. “It has really defined a singular definition,” Jensen says.

The multiplicity of curatorial voices, display media, and ideas at work in Horizons has proven revelatory. Whether poring over individual pieces in the museum’s collection storage while exchanging stories with members of the advisory committee or learning how younger artists in the show conceptualize their weaving practice, Jensen indicates that she learned much while organizing the show. It’s her hope that visitors to the museum access similar revelations.

“I hope visitors really think about the knowledge that is behind both of these art forms and consider weaving in particular as a cultural practice and record of lived experience. If each visitor walks away with just one question, as a curator, I’ll have achieved something wonderful.”

The exhibition—which was made possible by sponsorship from France A. Córdova and Christian J. Foster, the Terra Foundation for American Art, Tom and Mary James, and the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs—will be accompanied by a book, to be released next year by the Museum of New Mexico Press.

Just as each weaving can represent a record of lived experience, Jensen notes that the works in Horizons are animated by the history and knowledge that every person who steps into the gallery brings with them, extending and expanding that record, making it more collaborative and profound. “People activate the art,” she says. “Every visitor gives it a life of its own.”