New Mexico Museum of Arts, Santa Fe

May 25 – September 9, 2018

I’ve always maintained an irrational but polite envy of the orderly and meticulous artist whose studio is swept daily, whose works are steadily recorded, and whose supplies are inventoried as you might find in a Container Store advertisement. While I have not toured Frederick Hammersley’s studio, I imagine just that: a highly organized environment, queued up and ready for him to start his next “hunch” painting. Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking is a master class in scrupulous practices that streamline an artist’s ability to work. Distractions peeled back through repetition, painting ideas quickly assembled as thumbnails for visual reference—these are strategies of making to quell the interference of daily life. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Organized by the Huntington Library, To Paint without Thinking is a thoughtful survey of sixty works, primarily focused on Hammersley’s creative process, and the exhibition ultimately comes across as academic. For context, understand that Hammersley predates the Ferus Gallery “Cool School” and is a part of Los Angeles’s postwar art world inception with Karl Benjamin and other hard-edge painters. Broadly, Hammersley was a part of the West Coast era of Nicholas Ray, Miles Davis, and Richard Neutra, whose optimism and utopian ideals formed bonds of minimal forms with industrial sensibilities. So what is not immediately available in this show is the warmth of Hammersley’s temperament and charm. Admittedly, the organizers touch on the humor found in his long lists of titles, of which some are assigned to paintings only after works are completed. Titles like See Saw, Four Awhile, and Half a Bufferin receive high marks as witty observational jokes. Glimpses into the joy of making are also readily found at a table in the exhibition of a stack of collateral materials that includes manuscripts of past lectures (which are also available to read at bit.ly/hammersleywritings, thanks to the Hammersley Foundation). I recommend you start with The Care and Feeding of a Painter.

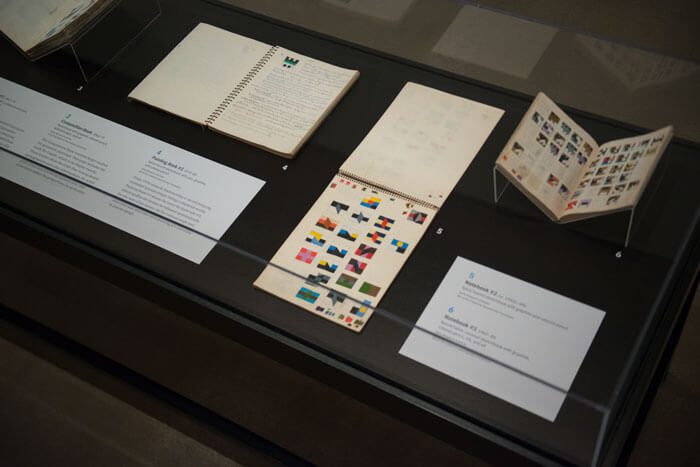

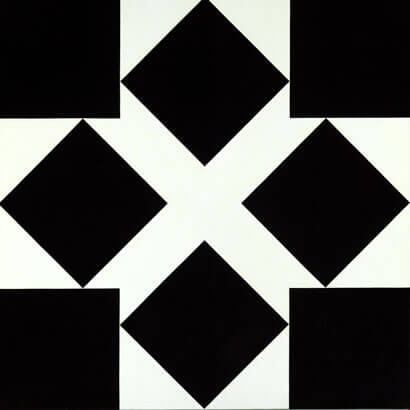

Hammersley is an early practitioner of system-based painting, a process that produced what he referred to as his “hunch” paintings. It involved visualizing and assembling many variable combinations of shapes and colors into thumbnail studies in his “Painting Books,” some of which are on loan from the Getty Research Institute. From the studies, Hammersley would decide which to realize into a painting. See Saw, #3 (1966) is an essential Hammersley painting: shallow space; concrete, non-objective, and symmetrical; pared-down palette; clean paint application with materials that reflected his contemporary technological innovation, Gelvatex (an industrial vinyl latex paint intended for exterior application on large-scale commercial buildings, which worked perfectly as a ground to handle air moisture exchanges from arid to humid climates). Hammersley was very concerned with his paintings as objects and paid close attention to how they would age, and it shows. No fogging, no blooming, the paintings in this exhibition could have been made yesterday. It’s difficult not to conjure Malevich. In See Saw #3, tension bands exist between a center “X” and outer cross that’s created by balanced masses. In the white intersection of this tension band, a type of slow painting buzzes in and out of focus. Similar in experience to Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings, the work reveals itself slowly and rewards the patient viewer with an illusion of foggy light bars after an extended gaze. Imagine the hum of fluorescent tubes. This is achieved by Hammersley’s super-flat paint application with a palette knife. Be present with the paintings, and they’ll open up. I promise.

The real surprise of this show is the set of computer drawings from 1969, gifted by the Hammersley Foundation. These works were made during a transitional time for the artist after his move to New Mexico to teach at UNM. In her catalogue essay, Nancy Zastudil shares that Hammersley hit a wall in his studio practice at the time and decided to take a computer drawing class utilizing UNM’s new IBM computers and printers with the program language Fortran IV. Like Gelvatex, the computer drawings are another example of the artist making the most of new technologies and innovations around him. The works are simple constructs of patterned characters that build formal structures similar to his paintings. Frederick Hammersley’s impact on the New Mexico arts community is permanent, and his presence is alive through shared conversations with his friends and students. If Hammersley is new to you, spend time researching the Hammersley Foundation’s website, where you can also make an appointment to tour his studio in Albuquerque. They are a resource.