We took a seat at the table in the center of the warehouse-turned-home (turned-“work, brainstorming, and studio space”) where artists Cannupa Hanska Luger and Ginger Dunnill live in Glorieta, New Mexico. Taped to the kitchen cabinet was a wall-size paper schedule of impending deadlines for numerous projects.

Every line was filled out, and notes were made in black marker, even in the margins. “Welcome to my life,” Dunnill laughed as, never skipping a beat, she outlined their individual projects—while the couple’s two children ran in one door and out the other, followed by an ambling cattle dog named Roscoe, passing by the cat snoozing peaceably on a bed of stuffed animals.

Their home is the central hub for all aspects of their busy lives, every element of which bleeds into the others. “There’s no separation for us of any of it,” Dunnill explained. “Of failure, of success, of children, of work, of play. We incorporate everything; we’re super holistic in the way we live.” The convictions with which they live are further underlined by the projects they’re working on and how they’re bringing them to bear. Among those is 2020’s Settlement, a massive art event in Plymouth, UK, marking four hundred years since the Mayflower headed west. Luger is the lead artist and Dunnill the U.S. organizer. They have invited twenty-seven other Indigenous creatives to live and work at different intervals in a large-scale public art installation in Plymouth’s Central Park. Each artist will also produce individual performance, music, and installation art during this time. The morning we spoke, Luger also had pieces of a ceramic sculpture for 516 Arts’ upcoming Species in Peril exhibition in the kiln. Dunnill not only manages Luger’s career but is a curator, organizer, creator of Broken Boxes podcast, and multi-disciplinary artist, often working in sound and performance. Later that evening, she was flying to New York City, where she and collaborator Demian DinéYazhi´ were performing their ASMR sound piece, Burying White Supremacy, which premiered at the Whitney but this time around was being performed at Brooklyn’s Smack Mellon.

Dunnill and Luger shared two mottos that are important to their individual and shared creative practices—which, of course, have inroads into every other part of their lives: “fail fast, fail often,” and “one step closer to almost being done,” which they offered with a laugh, suggesting that it was the stuff of an inside joke. Yet it speaks a resolve to move forward. Despite how hectic their lives seem, they each have an easy way of speaking, and their home and work space exudes warmth. That way of moving through the world, with humor and clarity of purpose, may just be how they get it all done.

Maggie Grimason: What have you been working on lately?

Ginger Dunnill: The most important thing to talk about is Settlement, which he got invited to do by the Conscious Sisters, a socially engaged art collective in Plymouth, UK.

Cannupa Hanska Luger: Initially they invited me to do something as an individual related to that, to have an Indigenous voice. You’ve got to understand how problematic that is, to have one person represent 562 different tribes. I’m not even Wampanoag [the tribe who first engaged with the pilgrims]. By the time the pilgrims got to my people, they weren’t even pilgrims anymore. They were more like an army. What I realized was, I needed to bring more artists. As it exists right now, we’re bringing twenty-seven different Native artists from different countries. It’s still not enough to really describe the conversation, but it’s the first time this conversation can be had in Europe where we’re not going to be celebrated in a historical or romantic context. With twenty-seven different artists, we get to contradict one another—which is true to form when you’re dealing with 562 different nations.

GD: We’ve got the artists, we’ve got the location, we’ve got the Indigenous-led programming; now we just need to raise the money. I’m doing what I can so that we raise the money for twenty-seven people who I believe in. In my work as a producer, that’s where my strength is: giving a shit. Then Cannupa gets to be on-site with them and take care of them there, and something radical can happen. This will be a historic event.

CHL: At a global level, there is a perpetuated expectation of Native people, and they’re often disappointed when it’s, you know, me. It keeps us in this historical context, rather than being part of present time, which is toxic. I think it’s killing our youth. I think it is one of the drivers of high suicide rates, drug addiction, alcohol abuse—this lack of visibility and not being seen in a present-day context. I think Settlement creates an opportunity for Native people to describe their own experience, and contradict one another.

Does that bring challenges, and does it feel like a great responsibility?

CHL: It’s a reverse colonial experience, where rather than being catty about it, we play with all the definitions. There’s a drive for me to walk around Plymouth and plant flags all over the place and say, “Hey, look what I discovered.” But that’s cynical. Let’s really hash some of this stuff out. Let’s talk about who we are, what we represent, how we’ve survived and maintained culture under colonial power structures and forced assimilation, because that’s what it really is. What we can really bring to the conversation is—this being in 2020—we have hindsight, we have perfect 20/20 vision. We have the opportunity to understand what we’ve experienced and push that story forward rather than standing in a place of victimhood.

What is the danger of cynicism?

CHL: There’s no resolution in that. It’s fun, and there’s space for that. There’s space for humor and cynicism in these contexts. But we’re not fucking around. That’s what it comes down to. We are deadly serious at this point with the work that needs to be done, and cynicism is no way to heal ourselves or to unravel some of this trauma—not just for ourselves, but for everybody. We need to remind people that we’re all victims of the systems that we are a part of, and cynicism, at this point, just reinforces it.

A lot of people get caught up in a wheelhouse of almost complaint-based work. They forget that they can begin to be that shift they wish was present. Instead of attacking the system, create a new system. I could spend my energy trying to fix that broken thing, or I can create from the ground up.

GD: I think that’s a real struggle for our generation of art makers. A lot of people get caught up in a wheelhouse of almost complaint-based work. They forget that they can begin to be that shift they wish was present. Instead of attacking the system, create a new system. I could spend my energy trying to fix that broken thing, or I can create from the ground up. A new beginning, the seed of a new thing—that’s what both of our work strives to do.

CHL: The world—and nature—abhors a vacuum. If we dismantle a thing without having something to replace it, something more awful will replace it. So, let’s create the opportunity for something new and let it grow, and if it grows and is supported, then it destroys the other thing in the process.

GD: And there’s room for everything. Every angle needs to be hit. We need to realize we’re all working towards the same goals; we just have different tools and different tactics. We can’t be ripping each other apart. I see that a lot, and it hurts. We could be moving forward in such good ways if we gave each other breath and space, and if we were honest with each other.

Making room for broad, unstructured narratives was foundational for Broken Boxes, right?

GD: I think that’s kind of the ideology that I live by. I think that sometimes we feel so alone… It’s important to find places where you can be yourself with your peers, where we’re connecting as humans and creating spaces where we’re forced to be together and hear each other’s stories all the way out, and then share that so that people can hear it and not feel like they’re hated or alone.

How is art particularly good at envisioning these new futures?

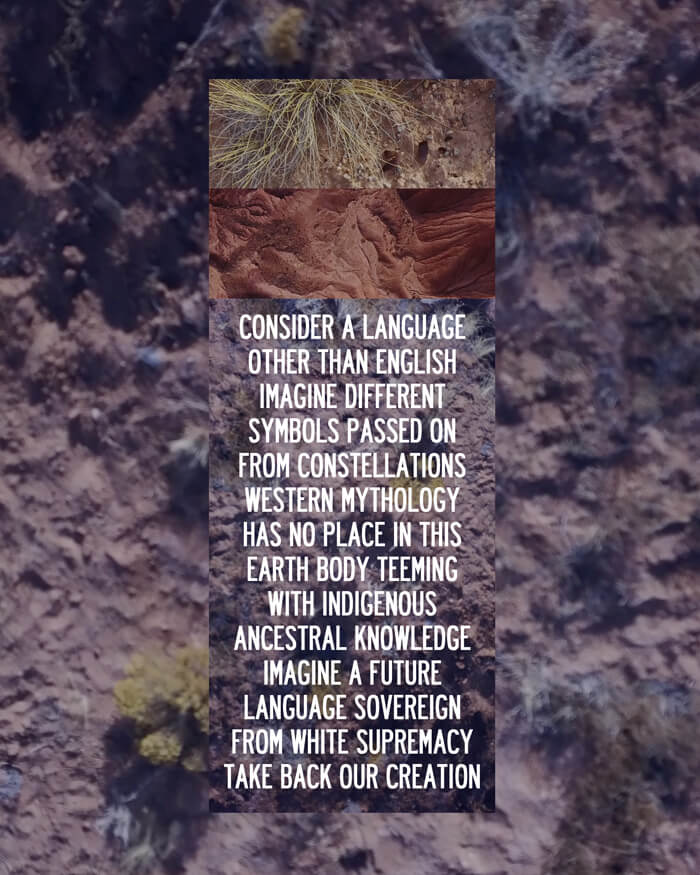

CHL: There are visual languages in every culture, and they have the ability to communicate beyond a lot of language barriers. These things tell stories without my having to be there to tell you that story. There’s room within art as a conduit for change that has always existed, in every single cave painting, every single pot we dig up. The majority of our human experiences, as upright, thinking, walking machines, is embedded in an art history. This isn’t a new thing; it’s a really old thing. I think our brains are hardwired to receive information from that. At its core, every single art piece that’s ever been made is narrative: it holds some sort of communicative function. That’s why I think art works really well, because it existed before we were even human beings, when we were homo sapiens sapiens. I’m putting all my chips in something older than me. I believe in it.

The majority of our human experiences, as upright, thinking, walking machines, is embedded in an art history. This isn’t a new thing; it’s a really old thing. I think our brains are hardwired to receive information from that. At its core, every single art piece that’s ever been made is narrative: it holds some sort of communicative function.

What is the role of ongoing-ness and destruction in your work?

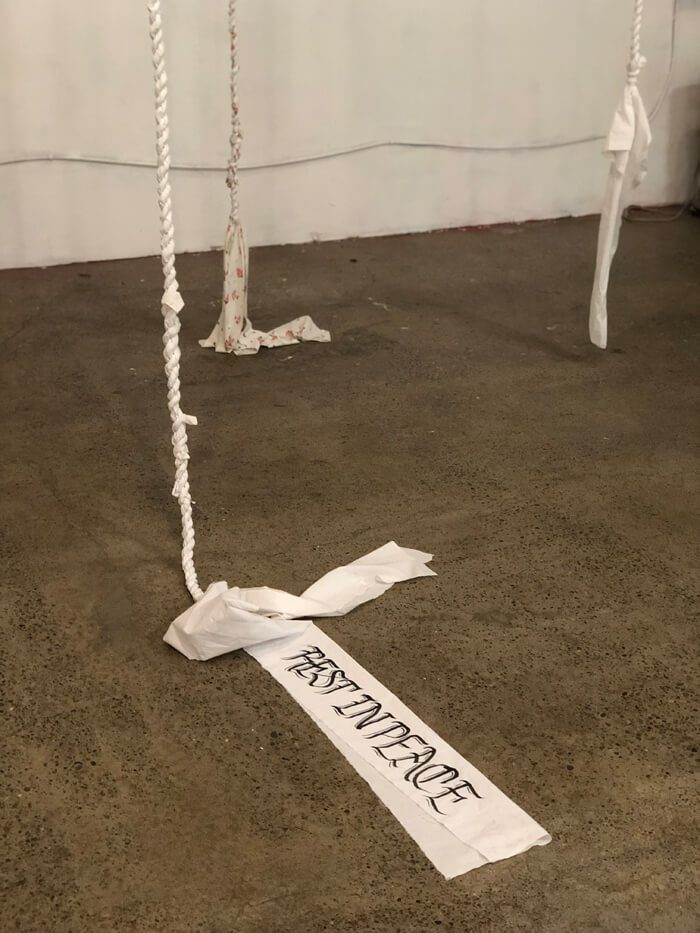

GD: It’s more about creating the thing that you’re not seeing. We could just be sitting here complaining about the things that aren’t, and that energy would be wasted. Trying to knock down some other shit versus build it, you know? Destruction is an important metaphor for letting go.

CHL: It’s inevitable….[In my exhibition, Stereotype: Misconceptions of the Native American, at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, 2013] they were really excited about the performance, the destruction of the objects. I was like, the whole point of putting stereotypes in ceramics is that all I have to do is let go. If I actively break these things, then what was the point of making them out of such fragile, gentle material? I literally just have to let go, and they’re doomed. It’s not even destruction: it was a cathartic letting go. Ideas are not subject to entropy the way our corporeal experiences are. The use of destruction and breaking stuff has less to do with destruction and more to do with—what do we do from here? How do we move forward? How do we pick up the pieces? How do we learn from these sorts of things?

GD: One of my biggest drives in supporting Cannupa’s career is that I believe the work he does as a Native American artist needs to be put in as a timestamp of where we are and where we are heading. I feel a duty to the work he produces and the way he thinks and believe it needs to be put into the collective consciousness. I have a skill set that can support that, and that idea is also part of my work—the idea of existing before and after and beyond. You can’t take it with you, but, so, what are you going to leave behind? Is it shitty or is it something useful? It’s like we’re building toolkits.

CHL: Go-bags for the future. What are the most important things, and what’s just dead weight?

Is that the map for going forward in your lives and art-making?

CHL: We travel, we engage with people, and that opens up our ability to communicate across these things. We break boxes and build bridges. I think, as artists in the world, I always joke that we’re social engineers—that’s my function more than anything—to build a bridge from all of my experiences to all of yours, and that is something we can cross. “Artist” undermines what we actually do. There are ways to do everything artistically, beautifully, with aesthetics and meaning. That whole definition needs to be re-established.

GD: I completely consider myself an artist. Compassion and giving a shit and being thoughtful—those are all forms of art. I’m working on ways to use my empathy as an art to organize, mobilize, and produce events, and recognize the wake that an organizer has. It’s incredible power and privilege to positively impact other people. It can go well, it can go badly, and that’s where craft comes in. People who support artists are artists, and more of these people need to be recognized in a way that honors what they do. Cannupa talks a lot about how he has never done anything alone. I think it’s time to put down that toxic individualism.

How do you do that?

CHL: I get this position of being in front of people and talking and saying what’s what—

GD: —and using your access to kick the door open wider. Not letting it shut behind you.

CHL: Really, the thing is not that people close the door behind them; it will just close by itself. Major institutions and the systems that we live in—especially as a person of color or any marginalized person—when you get invited to the table, you’re expected to be so goddamn appreciative, because you don’t usually get to sit at this table. So you sit on your hands and say, “Thank you. It is such a privilege to be here.” But the reality is, it’s a complete fucking privilege for those tables to have people like us there. Don’t forget how much you bring to that table, that your perspective is something they’ve never experienced. The idea is that there’s not enough resource, and if you don’t behave, you won’t get invited back… We have to get over these mental constructions so that we might be able to have honest exchanges. Let’s be honest. Let’s be vulnerable. That creates opportunities that have been beneficial in creating our go-bags for the future.

So you sit on your hands and say, “Thank you. It is such a privilege to be here.” But the reality is, it’s a complete fucking privilege for those tables to have people like us there. Don’t forget how much you bring to that table, that your perspective is something they’ve never experienced.

It’s a challenge in everyone’s life to discover what feels authentic and honest to them.

GD: And then when you discover it, it changes.

CHL: That’s the beautiful thing about honesty: it’s not rigid. Honesty is based on your experiences, so, if you’re becoming more experienced, then your honesty changes.

GD: There’s so much work we’re doing now, and it’s only getting bigger and more exciting, and we’re totally committed to that idea.

CHL: Exactly. One step closer to almost being done.