Amy was unyielding. Every time I saw her, she’d ask, “Have you gone to church yet?” “No,” I’d reply, again. “They’re about to start construction on the new sanctuary,” she’d announce with more emphasis each time, noting that, “They need you! Moving the Girard altarpiece to the new sanctuary is sure to be a HUGE deal!”

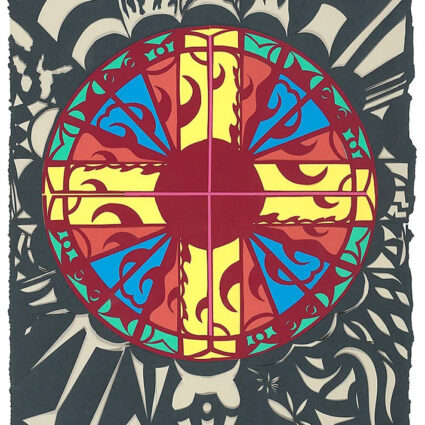

Despite my reluctance toward organized religion, being a Unitarian—a spiritual seeker who finds faith in any and all paths (even and including none)—I missed “my people,” and I went to church. The original sanctuary of the First Unitarian Church of Albuquerque is a bastion of another time, a modernist red steel cube designed in 1964 by architect Harvey Hoshour, who would become the architect for Alexander Girard’s collection at the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA). Architecturally, for me, the church was okay. The forty-foot-long by eight-foot-tall, five-thousand-block reclaimed wood altarpiece mural decorated with symbols of many of the world’s religions? Now that was truly special. While I didn’t know much about midcentury design— and, as a preservationist, I didn’t really know anything about modernism—I thought maybe I could still help with the massive project of relocating the mural. I had already run one project so complicated it ended up being half historic building documentation and half archaeology dig, and I had designed and installed a horse-shaped labyrinth so large you can only see it from a plane or a Google Earth satellite. I felt like maybe I “got” fringe architecture, and I (finally) offered to help.

I did not know that the mural was already threatened. Dozens of tiles were loose, and any vibration would shake them to the floor. Construction on the new sanctuary a few hundred feet away was about to begin. Once they started installing foundations, with those kinds of vibrations, it was clear that we could be looking at thousands of problems. So we set about documenting the mural. Working as if it were an archaeology site, we laid a grid over it so that the rows and columns of tiles were each labeled with numbers and letters. A team of congregational volunteers jiggled each tile as if checking for a loose tooth, then removed any detached tiles and made a pencil notation on the upper right hand side before returning them to their correct locations, so that we would know where to put them back when they fell. I interviewed conservators from MOIFA and Marshall Girard, who had helped his dad collect and prepare the wood for the installation. This offered us an exceptional glimpse into Girard’s intent and techniques for using wood from barns and stockades all over the Sandias to tell the church’s story. Dozens of plastic boxes were donated to transport each column’s worth of tiles to the new sanctuary, and the church hired a professional art contractor to remove and re-install the mural. The final result is an even more breathtaking view of the mural in the larger, lighter new sanctuary.

I did not know that the mural was already threatened. Dozens of tiles were loose, and any vibration would shake them to the floor.

The mural project was the beginning of my love affair with Alexander Girard’s work and his influence in New Mexico, which evolved as I researched the mural and then tried to place it into context in the development of his aesthetic. After that project wrapped, I had the opportunity to write articles, lead tours, and do talks about his work and his other designed sites in New Mexico. As time went on, I kept researching and interviewing, digging a little deeper into his story with each exploration.

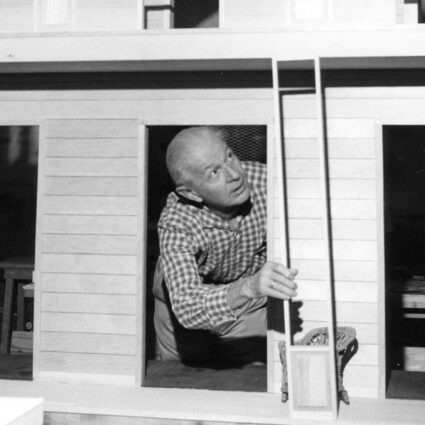

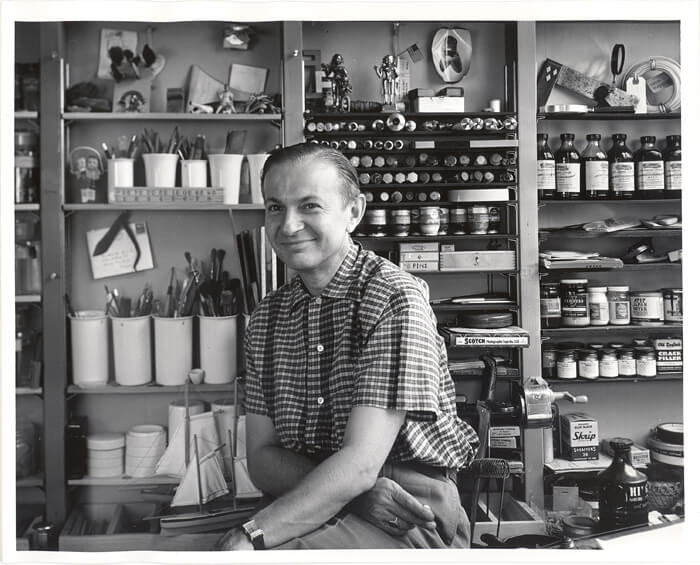

One of the most influential interior and textile designers of the twentieth century, midcentury modernist Alexander “Sandro” Girard moved to Santa Fe in 1953. After completing architecture school in Rome in 1929, receiving architecture honors from the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1930, starting his own firm in Florence in 1930, moving to New York to open his design office there in 1932, and then moving to Michigan in 1937 for what could only be described as an extraordinary career in defining space, Girard was already exceptionally successful by the time he got to Santa Fe. Girard explained his 1500-mile relocation to friends with a list as colorful as his design aesthetic: “1) This is the most ultra-fantastically beautiful place. 2) Crystal clear, crisp air at night and early morning—you want the sun when it comes out hot. 3) Sunsets better than any postcard. 4) Fires that smell like incense. 5) Horse, goats, cows visible from our portal. 6) Procession past our house, singing, at night, lit by small bonfires along the road. Mysterious—incredible.”

Girard, who said the light in New Mexico reminded him of Italy, loved New Mexico’s varied landscape so much that he proclaimed that “crossing the moon would be boring by comparison” to crossing the Rio Grande. His home, on a hillside adjacent to Canyon Road, became a place of experimentation where Girard test-drove the conversation pit—a sunken entertaining and living space—as well as various iterations of furnishings, decorations, boxes, benches, tables, and displays, which he arranged and rearranged in ever more inspiring displays. He implemented elsewhere the finessed design ideas he worked out here, like the familiar explosion-of-reds-on-white conversation pit he designed for architect Eero Saarinen’s Miller House in 1957.

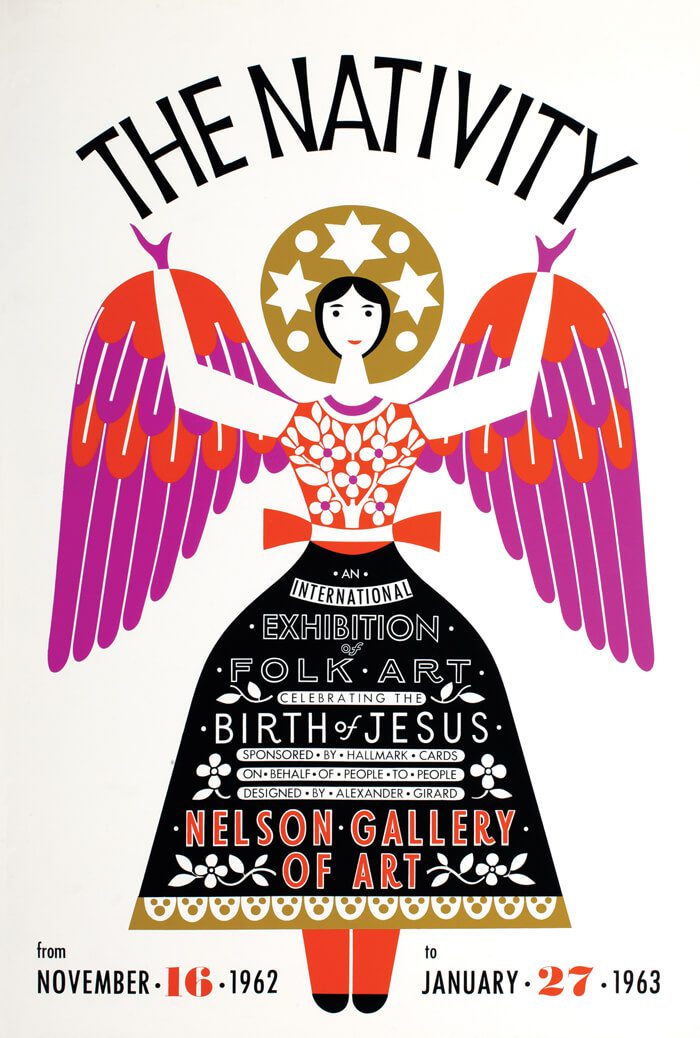

After procuring several Russian folk art dolls in the 1920s, Girard and his wife, Susan, started really collecting in 1939, when they brought home a carload of folk art from their honeymoon in Mexico. By 1978, the year they donated their collection to the Museum of International Folk Art, their worldly assemblage consisted of more than ninety thousand toys and seventeen thousand “other” folk art pieces. Girard assembled these into dozens of “sets,” as if they were part of an elaborate stage production he was directing for the Museum’s central exhibition, Multiple Visions. The vignettes are not just an homage to Girard’s quirky aesthetic sense, but some are also deeply connected to this place and our people. In the Pueblo set, for instance, Girard brought in women elders from Cochiti to make sure that the scene depicted was one that Pueblo leaders could stand behind.

The Kingdom of Fife, for which Girard created monies, flags, standards, heraldry, stamps, passports, a language, and symbology, existed in a fantasy world Girard invented when he was ten years old, called Celestia.

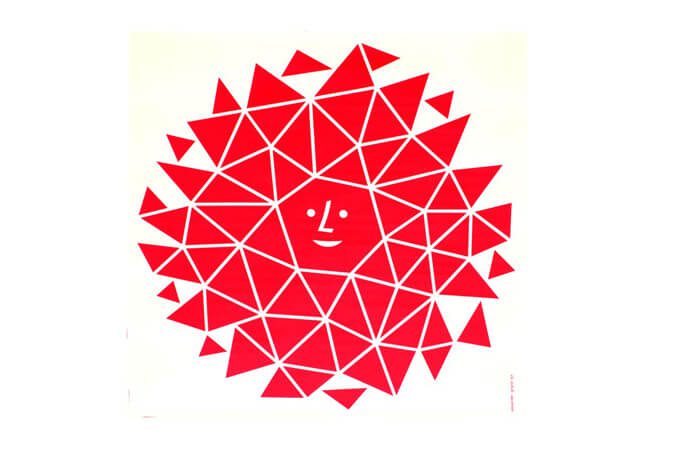

A new exhibition of Girard’s work from the Vitra Design Museum will be at MOIFA from May 6 through October 27, 2019. (The exhibition is free to New Mexico residents the first Sunday of each month!) This will be the first time that Girard’s design work and his folk-art collection are shown side-by-side. Vitra’s show, A Designer’s Universe, is a selection of the best of his work, including sculpture, textiles, furniture, photographs, and drawings compiled from his personal archives of some five thousand sketches and seven thousand photographs. The exhibition will feature a multi-media, multi-dimensional timeline, from his projects with Eero Saarinen and Charles and Ray Eames to my personal favorite: a world of his childhood creation that formed who he was as a designer. The Kingdom of Fife, for which Girard created monies, flags, standards, heraldry, stamps, passports, a language, and symbology, existed in a fantasy world Girard invented when he was ten years old, called Celestia. He wrote several “books” on vocabulary and symbols for his special language, and two(!) on its grammatical usage. He initiated his parents and two friends into his world, and they wrote to each other in his special language throughout his life.

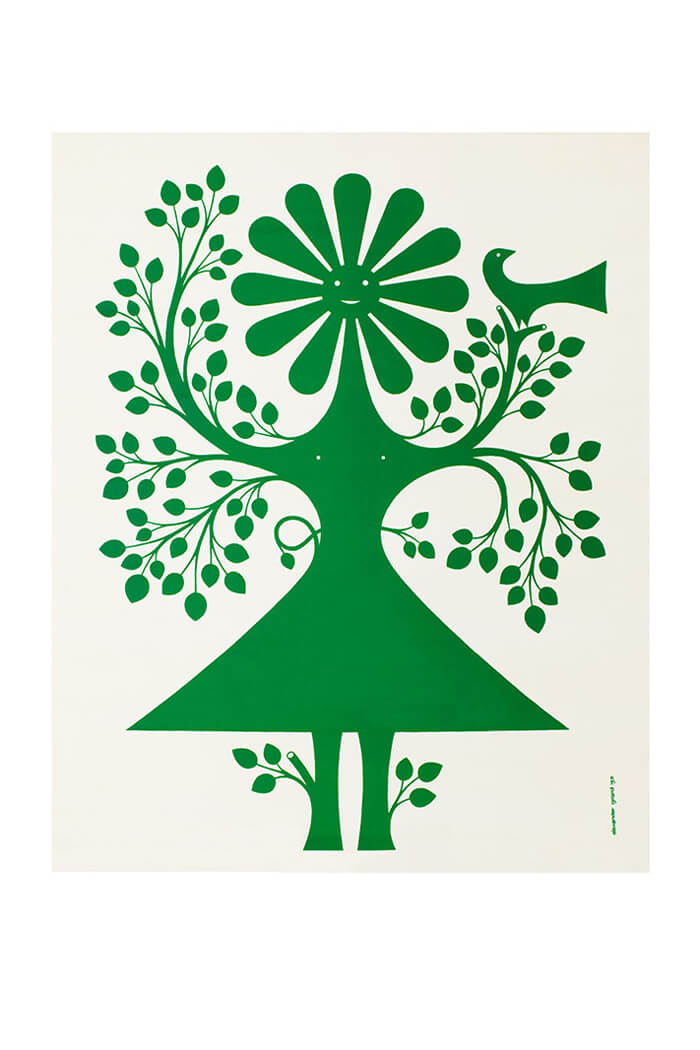

Set against each other, these two shows will allow an unparalleled glimpse into the mind of the maker Girard was. And, while it feels almost like a secret, the part of the exhibition I am personally most excited about will be downstairs, where MOIFA curator Laura Addison has put together a mini-exhibition that sets Girard’s design work against the backdrop of the folk art that seems to have inspired it.

/

The Compound, Girard’s last intact restaurant, completed in 1966, maintains its sunken bar, patchworks of Navajo blankets, food folk-art vignettes, and perimeter bancos, which also defined his interiors at La Fonda del Sol (New York, 1960) and L’Etoile (New York, 1966). Interestingly, like his 1968 The Magic of a People exhibit at the HemisFair, The Compound décor includes a tree of life, a snake, a golden sun, and a silver moon, suggesting that the symbols represent Girard himself—or an idea he bestowed onto the architecture through their use.

John Gaw Meem brought Girard into design furnishings and décor for St. John’s College’s Peterson Student Center in 1964. Girard produced a simple interior with mostly white and neutral tones, wood finishes, pops of color for special spaces, and vibrant intermingling colors on doors. Girard’s painted mural of thirty-six symbols beside the main entrance expresses the college’s liberal-arts values. (And the mural has one mistake!) The Center can be visited any time, and be sure to visit their concurrent exhibition of Girard’s drawings for the school in their second-floor gallery.

Girard’s influence here doesn’t end with his own work, either. There are nods to him all around Santa Fe and New Mexico. Dozens of conversation pits were built in the 1960s and ’70s. Architecturally, they helped define a very social generation in our history. The newly renovated El Rey Court hotel was inspired by Girard’s work at The Compound, as well as his style of storytelling though symbolism. Los Poblanos Inn in Albuquerque has three suites decorated with Girard and Girard-style works, folk art, and fabrics. The east wall at the shopping center on Baca Street where Counter Culture is located bears symbols that seem to nod to Girard’s murals.

For the church, Girard’s mural represented the binding together of varied wisdom traditions and values.

Researchers like me are even now finding forgotten connections between Girard and some of our extraordinary locals, from Georgia O’Keeffe (who painted two previously missing, just replaced miniatures for the Italian Villa set at MOIFA and helped him prepare for the 1968 HemisFair) to Eva Fenyes (who, with her daughter and granddaughter, designed and built the quintessential example of Santa Fe Style architecture, the Acequia Madre House). As historical collections are donated to museums and repositories, as witnesses document their stories, and as these archives come online, each gift uncovers new branches of this extraordinary tale, which, I’m happy to say, has caused me to fall a little in love—not only with Girard’s work but with modern art and architecture.

One of the highlights of the past couple of years for me was a fashion show at MOIFA, where the atelier Akris launched their fashion line based on Girard designs, to the delight of an elated audience packed with creators and visionaries. Surrounded by his extraordinary folk art collection, I smiled, thinking that the colorful characters that had come together around his work would probably please Sandro greatly. Just take a look around the Multiple Visions exhibition. Each unique “set” is fundamentally the same: it is a story, frozen in time, of people coming together to celebrate a moment of our shared humanity.

When I first joined the Unitarian mural project, I was reminded that the Latin word religio, from which “religion” is derived, means to bind together what has been separated. For the church, Girard’s mural represented the binding together of varied wisdom traditions and values. This idea deeply resonates with me, and I think it is the greatest gift Girard has given us. It seems to me that he really wanted everyone to respect and, perhaps, inspire one another.