SITE Santa Fe

April 13 – May 16, 2018

Since 2000, SITE Santa Fe’s Young Curators program has given high school students the opportunity to plan every step of a museum exhibition. Students from across New Mexico meet weekly to plan an exhibition theme, create calls for artwork, jury submissions, and install the exhibition. They plan the publicity and marketing campaign as well as the opening events. Young Curators alumni have gone on to successful art careers themselves, often staying in New Mexico to contribute to their local communities. This year, SITE Santa Fe’s Young Curators opened Guises, an exhibition whose works all address the concept of identity. The exhibition’s contributors, who range in age from twelve to twenty-four, approach identity from a spectrum of viewpoints. The result is a multifaceted and often introspective display of young artists who are finding their voice and experimenting with diverse visual languages.

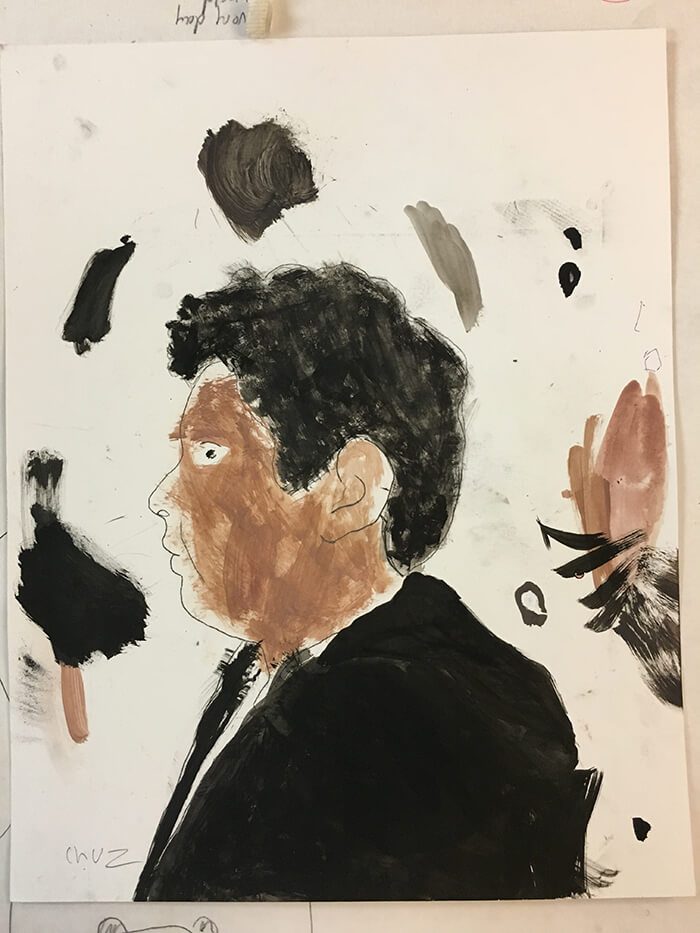

As the title Guises suggests, the identities on display in this exhibition are anything but straightforward. The Young Curators seem to have deliberately chosen artists whose works complicate notions of identity both from an interior and exterior perspective. Twelve-year-old Cruz Garcia’s self-portrait depicts the artist in profile against a white background with a few gestural marks filling in the negative space. But the work’s title, Is This Me?, thrusts the painting into a philosophical realm, and we are left thinking about the complicated relationship between identity and its representation. Other works of self-portraiture explore this divide between self-representation and one’s place in the world. Sara Vianco’s photograph Fear of Isolation, a blurred exposure of the artist’s head as it moves through various poses, suggests an inner turmoil in keeping with its title. Broadus Mobbs’ sculpture evidences trial and error as the artist explores his materials, adding layers of wax and hair to coax out a grotesque and malformed human figure, the evidence of his own process of understanding his artistic identity. Rowan Brown’s watercolor Don’t Look Back, like Frida Kahlo’s magical realist self-portraits, shows two renderings of the artist linked by the twining stem of a flower, suggesting Brown’s relationship to nature and to her own growth. In a more playful but no less poignant image, Greely Miller manipulates digital photos to show the head of an ostrich peeking out of a baggy-hoodied human torso: a portrait of the artist confronting his own fear of confrontation. Mark Joseph tackles the relationship of technology to identity in Digital Distress, a photograph that pictures multiple self-portraits in different costumes displayed as a shop window of televisions for sale, implying in turn the commodification of each iteration of Joseph’s many selves.

Clara Natonah presents a text-based work, a poem printed and mounted directly on the wall, which declares, “Every painting is a self-portrait.” This idea seems especially true for those artists in Guises who appropriate personal items to stand in for their own identities. Attacus Peknik presents a pair of decimated Adidas sneakers, which the artist wore during a trip to Europe as well as in more proximate venues such as Gallup, NM. Fallon Wrede, too, focuses on the quotidian with her video Untitled, which layers shot after shot of everyday objects (a twenty dollar bill, a tampon, a bandaged finger against a thick layer of fur, two animal jawbones mounted to a wall) into an image of the artist, or at least one version of her. Erin Elliott collages strips of newspapers and other media, such as a picture of Dolly Parton, a strip of film negative, string, and a drawing of a waitress into a mosaic of her interests. Elana Wallach uses old family photographs, onto which she sews dyed thread in linear patterns to activate the images and create expressive, narrative patterns that evoke and enliven the past.

Some of the most powerful work in Guises is by women artists who examine conceptions of femininity. Magdalena Ramos Mullane’s Scissors documents her process of cutting her own hair while lying on the floor, so a halo-shaped ring of auburn hair remains afterwards. In Suck It In, Bitch!, Lili Dale takes a series of photographs of her torso after removing a waist trainer, the reddened indentions tracing the often painful lengths women go to conform to often unrealistic standards of beauty. Isabel Collins’ Girl: 2:18 upends notions of propriety as she trains her camera underneath a bathroom stall, offering an illicit glimpse of legs and shorts. And in her oil painting Emergence, Savina M. Romero pairs expressive color with various poses of the female nude form to convey pride and spiritual strength.

As these works attest, gender is a significant factor for this group of artists and curators when it comes to issues of identity. I hesitate to make generalizations about “Gen Z” or to pigeonhole the artists whose work deal explicitly with gender, but it seems important to note the freedom with which these artists address their own explorations of gender identity and challenges to gender binaries. In what has become the iconic image of the exhibition, Elizabeth Hanselmann’s Gender’s Guise, a pair of clay masks (one dog and one cat) and a photograph of conventionally gendered bodies wearing those masks, brings home the notion that any gender identification is in part based on assumptions from outside observers. And Hawk Platero, in a stunning nude self-portrait underscoring his own gender fluidity, incorporates classical styling and setting to make his own plaintive pose appear almost saintlike.

In another photograph, Platero photographs himself shrouded in a red blanket, blindfolded, with a heavy turquoise and silver necklace. His body almost completely obscured and his eyesight hindered, Platero’s composition emphasizes the weight of his Native history and culture on his own sense of self. A feeling of living in two worlds, neither inside nor outside, is also a theme in Marcela Gutierrez’s video I am pt. 1, in which she chronicles her experience growing up as an immigrant in the U.S.

Some artists veered into near-total abstraction in an effort to represent relationships rather than straightforward identification of the self. In Mia Carswell’s A Constellation of Connection, encaustic squares read as bodies, while black lines and strokes of grey and yellow intersect with them in a map-like composition. Alex Mclaughlin’s painting Blank: A Story combines a series of biomorphic forms in a dark palette of reds, browns, and subtle blues with suggestions of musical notation and human figures. And in Tres Trasplantes, Hailey Tyra photographs a combination of plastic fingernails embedded into a tree trunk, a surreal allegory for humans’ relationship to nature, the disruption of the organic with the synthetic.

The Young Curators’ mission, as stated on the exhibition’s main wall text, is ambitious and clear: they “hope to transform the limited way adults often categorize youth.” Across the country this year, adults have witnessed teenagers actively protesting gun violence and advocating for human rights at a scale that is unprecedented since the 1960s. In a recent article on Slate, Dahlia Lithwick reported that the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School were uniquely positioned to speak publicly for their causes due to the exceptional training in journalism and debate that they received through their public curriculum. With programs like Young Curators, high school students are receiving an education not only in how to navigate the rigors of the art world, but how to find and to use their voices. Guises is a clear example of how these young people plan to use those voices to change conversation about issues that affect not only young people, but all people.