After planting and harvesting crops for over forty years, you would think a being might finally comprehend the ephemeral nature of all things. Not, alas, this one. At least not within my deep inner recesses, in the private folds of knowing.

Superficially, of course, I know. I’ve read Thucydides and Gibbon, tramped through the columns and battlements of temples and palaces reduced to marble gravel sparkling underfoot. Nothing lasts. And surely even less will last in a society that manufactures for shelf life and planned obsolescence and which only occasionally constructs for all time, or most of time, or at most for a few hundred years. As a society, we are young, ignorant, and foolish. We are told that the end is near. We don’t know just how near, though new calculations are announced almost daily.

Privately, childishly, irrationally, I believe otherwise, denying the likelihood that our little mud house and our farm will not weather flood or landslide or drought or fire or real estate subdivision or civil disorder or radioactive cloud, and that sooner or later all will fall into ruin or be swept away or torn down, leaving at best a few little mounds. What chance is there of extending your influence much beyond your own life and that of your children, in a house built by hand, in books written, in works of art? I can remember only a handful of details about the one grandparent I personally knew. Oblivion will come within a generation or two, if not sooner. In our heartbeat biological time, living memories quickly pass into the second hand, and these in turn become distilled into a phrase, a quip, a joke, a taunt, a photograph of a face no one knows the name of, an antique curiosity, a single entry in a genealogy, perhaps a leaning granite headstone, before these small traces are swept away. All that survives of my great-grandfather is a gold-headed cane engraved with his name, plus the memory of how he, as an old man, would polish the brass push plate of the swinging kitchen door of the Riverside, California, house, only to be irritated whenever someone left fresh fingerprints on it.

It is unbearable to think of the seas of hope and passion and suffering that lie in the soil underfoot, and in the water, and in the very air we breathe—when our own solitary pain can so easily become intolerable. And to imagine the pain and death and destruction that every advanced society feeds on, in the remote places of the earth, in the mines, the forests, the oil fields, the prisons and internment and refugee camps, and on the battlefields past and present. In order to live, we must deny the misery. Civilization is above all a state of continual denial, as is perhaps life itself—except for those who traffic directly in demise, such as the military, doctors, undertakers, butchers, executioners, policemen, journalists, all of whom work on our behalf, in our name.

History proves that nothing lasts. Or that almost nothing lasts. That bits and fragments and shards and DNA are the rule. Over the course of the next couple of hundred years, my village will wax and wane and perhaps even be abandoned in a time of extreme drought or from a meltdown at Los Alamos National Laboratory that blankets the region in radioactive dust. The river will rise and dry up and rise again, and perhaps the beavers will flood the field where we farm, rebuilding the topsoil they themselves first created millennia ago with their dams and ponds. Then, some distant day, some creature, some human rooting around in the earth, planting a garden again or a tree, may come across a thick, rough ceramic disk an inch and a half in diameter, with a hole in it, and on one side, embossed letters in a script that time has rendered indecipherable, EL BOSQUE GARLIC FARM or AJOS DEL BOSQUE, the letters circling an image of a garlic bulb in bas-relief. This future gardener, if human, may slip the disk into a pocket or sack or tie it with a string and hang it from his or her neck. The finder’s day may pass in wonderment at what the disk might have once meant and at whom those strange people might have been and what they once did on this land. In like manner, I have pulled from my fields rusty horseshoes, a bridle bit, fragments of metal spurs and have wondered about those who preceded me. And on the mesa above, there lie pottery shards pre-dating the Conquest by hundreds of years.

But why should we wish to be remembered, wish to become the exceptions, in the churning cycles of life that we both preside over as farmers and gardeners and are in turn presided over, within the upheaving geological cycles whose yawning eons are embodied in the very rocks that have witnessed generation upon generation of us heartbeat creatures tramping past? Why do we not simply accept the undeniable, the universal fate of the living? Why, instead, do we wish it all to go on forever, in some form or other?

Because perhaps both the comedy and tragedy of life lies in its capacity for denial, for pretending otherwise, for acting as if the universal consequence did not apply in this or that case, for imagining something quite other. The biological world, in us, in achieving imagination, the ultimate tool, the tool of tools, has broken through the limits of all living things. We will not live forever, but we can imagine living forever; we can imagine our works living on forever, and this perhaps is enough. A lie, the cynic may argue, but what else is the imagination, even the cynic’s, but a fluid or a gas that works unceasingly to dissolve or crack the nearly eternal certainty of the rocks, the stones, the boulders and seeks to escape limitations of all kinds and to hover over it all, for all time. Empires collapse, as this one will, but history lives on to re-invigorate what has been turned into piles of stone, in a triumph of imagination over time.

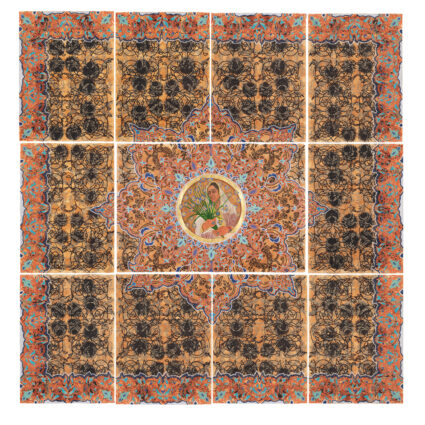

A succession of local potters has stamped out thousands of stoneware and terra cotta disks for us over the past forty years. We have tied them to thousands of garlic braids and bunches, sending them out into the world like notes in a bottle. In time, the garlic is either eaten or dries up; the white husks become dusty, and the arrangement is thrown away. But now and then, I imagine, someone cuts off the disk, puts it on a windowsill or in a drawer or ties it to the end of a closet light pull-cord. Now and then, a customer at the farmers’ market will hand us back one to recycle onto the next braid or bunch.

Perhaps what we are doing with these ceramic disks is sending spores out into the far distant future to prove that we once existed and labored and thought and felt. And also as a test to see how far our imaginations could reach, in time and place, through whatever extreme circumstances the future might impose on the Earth, in the form of simple ceramic disks, our private little plaques like those more public ones on buildings and by the side of the road and in public parks and those left on the moon and sent into outer space bearing hieroglyphic messages saying not much more than:

HUMAN, ALIVE.

Human, alive. That’s now and will always be now.

As for then, I’ll leave it to the imagination.

Excerpted from The Garlic Papers: A Small Garlic Farm in the Age of Global Vampires, to be published October 21, 2019 by Leaf Storm Press, Santa Fe, NM.