On the walls of major American museums, only 5% of artwork is by women. This statistic appears in the catalogue for the Harwood Museum’s current exhibition, which flips that number on its head. There’s a small display featuring some men upstairs, but most of the institution’s galleries are devoted to Work by Women. With a direct nod to the #MeToo movement in its wall text and catalogue, the show unearths little-seen artworks by women—all of whom lived in or passed through Taos—from its permanent collection.

That includes the space usually occupied by the Taos Society of Artists, a notorious boys club credited for founding the Taos art colony at the turn of the nineteenth century. It’s strikingly satisfying to find the only woman admitted to their ranks, Catharine C. Critcher, ruling the roost with her female contemporaries. Among the artworks is a luminous portrait by Elizabeth Lucy Case Harwood, who cofounded the Harwood Foundation and cultivated a circle of creative luminaries in these halls. In a rare sight, the painter Mary Greene Blumenschein hangs apart from her more famous husband Ernest, who was fiercely competitive with her.

One gallery over, a grouping of works by the Taos Moderns proves equally stirring. The movement shook up the Taos art scene in the 1940s, and saw a number of women rise to its forefront. It’s a thrill to find Beatrice Mandelman, Janet Lippincott, and Florence Pierce all in a row, with work by their forebears, Mabel Dodge Lujan, Eugenie Brett, and Frieda Lawrence (called the Three Fates by their star-studded coterie) just across the room. A 1930 lithograph of an undulating city canyon by Helen Greene Blumenschein, daughter of Mary and Ernest, is a cousin to Georgia O’Keeffe’s New York paintings. Three mixed-media collages by Mandelman from the 1960s, painted in the screaming palette of police lights in protest of the Vietnam War, are standouts.

During my visit, a chatty museum employee haunted the aforementioned galleries, ready to reassure visitors who were there to see the male contemporaries of these historic women. The men would be back on the walls soon, he said, but in the meantime he was authorized to usher particularly disgruntled customers down into the archives. The artworks that appear in Work by Women certainly haven’t been afforded this level of accessibility, though the anecdote does show how radical a move an expansive, all-female show remains for twenty-first century museums.

The rest of the exhibition is divided, for the most part, into thematic groupings that are alternately descriptive and vague. The rooms labeled “Homage to Place” and “Nature Altered” feel relatively unified, but try to guess what appears in “Insights” or “Essential/Sensual.” Aside from an introductory paragraph near the front of the show, there’s a troubling dearth of wall text to unify the works.

The rooms devoted to the early Taos art colonists (titled “Vanguard”) and the Taos Moderns (called “Postwar Dialogues”) work so well because the artists on view actually inspired each other and led their respective movements. The links get fuzzier outside of those galleries, illustrating a primary pitfall of curating a show based on gender. These women might be on view—in some cases for the first time in almost a hundred years—but they still don’t necessarily get props for the wider influence they wielded on the local and national art scenes. The aforementioned catalogue does provide some context, with essays by the Harwood’s director Richard Tobin and Work by Women guest curators Judith Kendall and Janet Webb, but their words will likely only reach a slice of the show’s visitors. They’re also mostly white women, exposing a jagged chasm in the Harwood’s collection. The show’s timeline begins with European descendants painting portraits of Indigenous women, but Native and Hispanic women were making art in Taos for centuries before that.

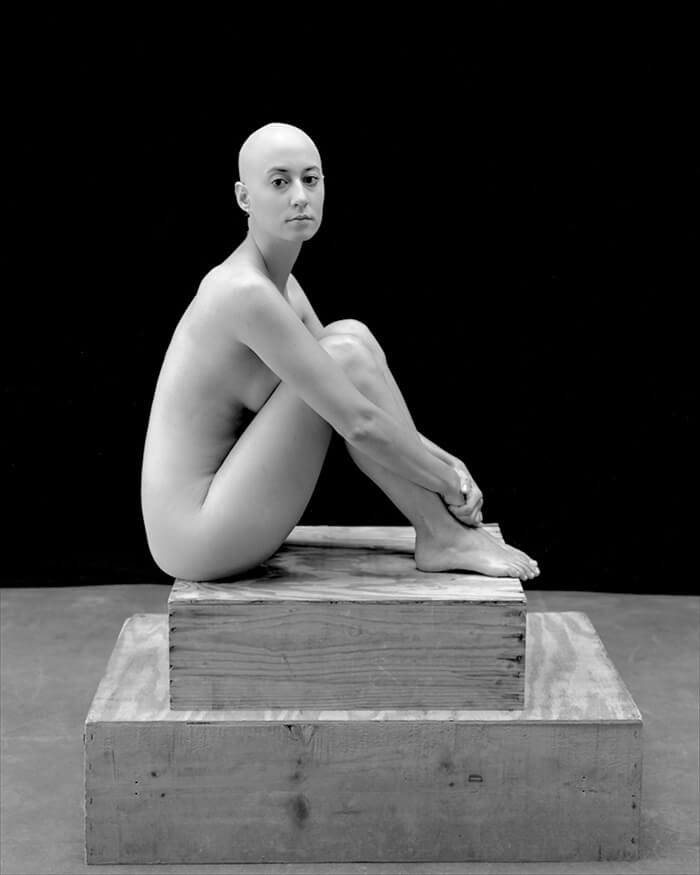

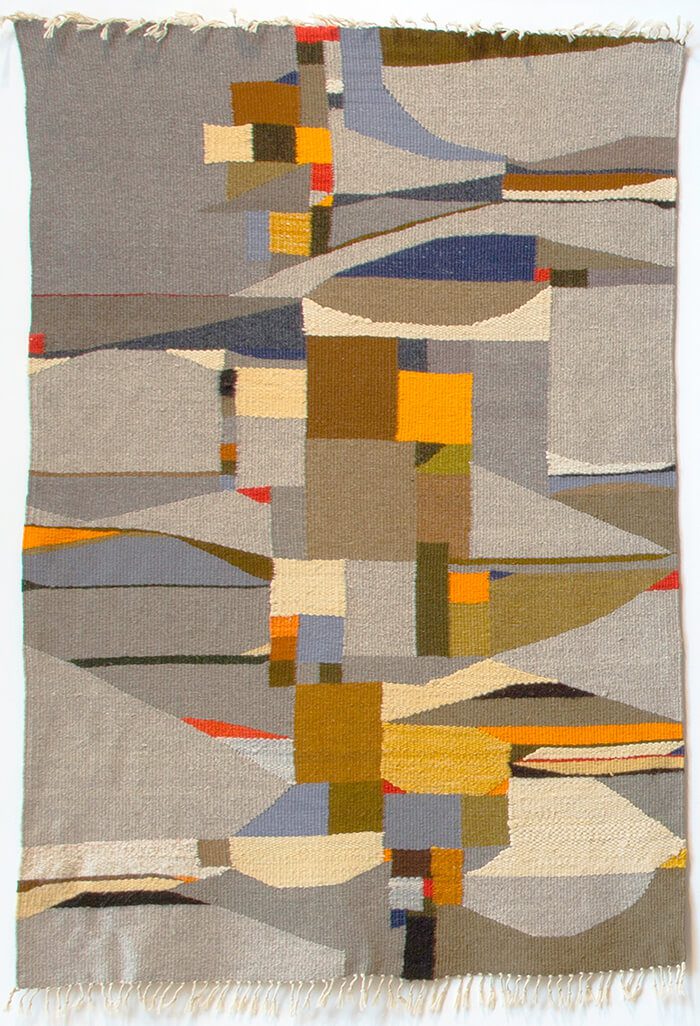

Still, there are significant treasures in every gallery, from a series of striking 2016 portraits by photographer Zoë Zimmerman at the show’s outset, to exquisite fiber artworks in the tradition of Rio Grande weaving by Joan Potter Loveless, Rachel Brown, and Kristina Brown Wilson (another Taos trio, known as the Three Weavers). Judy Chicago, Agnes Martin, Lynda Benglis, and Gene Kloss all make notable appearances.

Work by Women tries to address its representation problem with contemporary artwork by or about women of color at the exhibition’s back end. On the second floor, there’s a small display called “Taoseñas” and two figurative murals by Jolene Nenibah Yazzie. A solo exhibition of mixed-media paintings by Erin Currier, titled La Frontera, consists of exuberant portraits of American immigrants.

Nearby, a wall relief installation by Christa Marquez in the museum’s project space deserves a long look. It’s a ghostly forest made from swirling strands of tumbleweed that stir when you make the slightest of movements. The piece struck me as a metaphor for the challenges of re-establishing the long ignored role of women and other underrepresented groups in art history. Their stories are a delicate web that could easily blow back into this institution’s basement, especially when a massive solo exhibition by Larry Bell arrives in June. To preserve and strengthen the web, curators must retroactively root these women into larger art historical and critical contexts—and, in the process, present new ways of telling the whole story.