Springville Museum of Art, newly helmed by Emily Larsen, is one of Utah’s oldest visual arts institutions—and a crucial component of the state’s arts education networks.

Springville, Utah, is often labeled as a bedroom community by those commuting north to Provo or Salt Lake City. But for more than a century, the small city of approximately 35,000 residents has had a deep engagement with the arts statewide.

The Springville Museum of Art is Utah’s oldest museum dedicated to the visual arts, with a permanent collection of more than 2,500 works. Since its founding 120 years ago, the SMA has been intertwined with Utah art. The museum, which recently named longtime SMA staff member Emily Larsen as its new director, also displays 20th-century works from the U.S., Europe, and a curious and impressive collection of Soviet Realist art.

The SMA is also a crucial foundational pillar in Utah’s overall arts and arts education ecosystems, and has become a unique training ground for high school students thinking about pursuing creative careers.

“One thing I love about the Utah art community, and Springville is a part of this, is that it’s so collegial and collaborative,” says Larsen, who became SMA director effective January 3, 2023, replacing longtime and retiring director Rita Wright. “It does seem like we’re all working towards common goals.”

The beginnings of what would materialize into the Springville Museum of Art date to 1903 when Springville-born sculptor Cyrus Edwin Dallin, who has been called Utah’s first renowned artist, and John Hafen, a Utah-raised Swiss immigrant who studied art in Paris, donated art to Springville High School. The gifts created a springboard for other Utah artists to bestow works to the secondary school—and piqued the students’ interest in art.

In 1921, Springville High students held a Paris-inspired, salon-style exhibition—an annual show that continues to this day. Eventually, the High School Art Gallery, as it was known then, required expansion due to its amassed collection of artworks.

During the Great Depression in 1937, a new Springville Art Museum building was completed thanks to funds and donations from the Works Progress Administration, the city of Springville, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, students, and residents. Since then, the SMA has undergone numerous expansions and renovations, including a new wing in 2004 that doubled the museum’s footprint and the addition of the Sam and Diane Stewart Sculpture Garden in 2009.

The museum, which organizes more than fifteen annual exhibitions, remains grounded in presenting the work of established and fledgling Utah artists.

“One of our big goals with the high school art show is to help train the next generation of students [and] to give them the experience of participating in a professional museum show—what that means, what the expectations are, how to present your work and write an artist statement, and deal with a professional venue,” says Larsen. “It sets them up for success, even if they don’t become professional artists.”

A majority of the museum’s growing collection is Utah art past and present, which includes the work of Jeffrey S. Hein, Lis Pardoe, and Gilmore Scott (Diné), and reflects the institution’s mission of promoting and fostering art made by Utahns. SMA also boasts two smaller legacy collections buttressed by wide-ranging episodes of happenstance.

The annual spring salon used to be a countrywide show that featured entries from locals as well as big-name national artists such as Norman Rockwell and Rockwell Kent. Students would fundraise and pool together money to buy out-of-state artworks from the salon show, and those pieces eventually became part of SMA’s holdings.

An anomaly is the Soviet Realist collection—one of SMA’s most beloved displays—which came about in the early 1990s when a large group of collectors, including Utah folks, started traveling to Eastern Europe on business following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and dissolution of the Soviet Union. The collectors and a former SMA director became enamored with Soviet works that Larsen calls “incredible pieces of historical and cultural value that bring up so many interesting questions and discussions with our visitors and students.”

“The former director saw it as a teaching tool as well as an opportunity to bring large-scale, public, multi-figure academic painting to Utah to show Utah artists what kind of painting is possible,” says Larsen.

“It’s a really complicated collection that has a lot of different ways that you can approach it. That’s part of the fun of having it on display—you can talk about these art pieces and the academic tradition and training of the artists and look at them as beautiful art objects, and you can also talk about what parts are propaganda,” continues Larsen. “How do you decipher what’s propaganda and what is the artist’s voice? They’re rich conversation starters in addition to interesting art objects.”

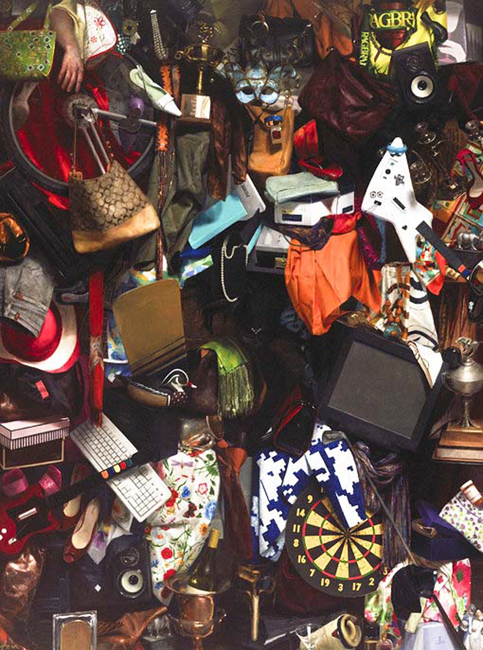

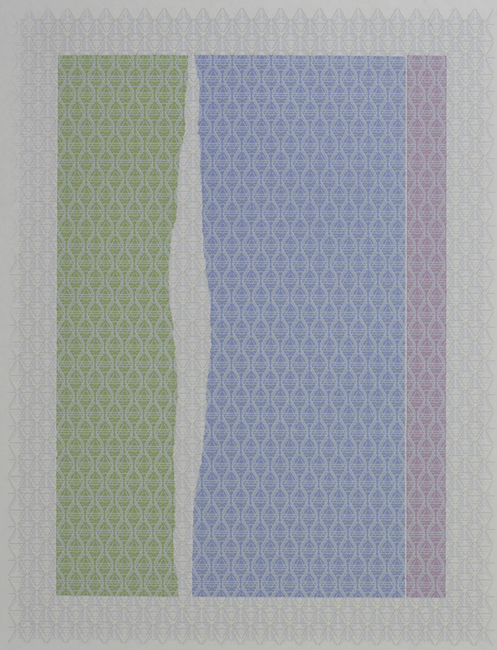

Larsen, who participated in last year’s Utah curators summit in Green River, succeeds Wright, who led the museum since 2012. Larsen, most recently associate director, is a longtime SMA employee who started in 2014 as an assistant curator and registrar before transitioning to head of exhibitions and programs. She’s also a Utah art researcher, scholar, and mixed-media collage artist.

As director, Larsen has set her sights on instituting a robust strategic plan, refining the museum’s programming, and continuing to work directly and indirectly with other Utah art organizations.

“The Utah arts institutions have different missions and focuses,” says Larsen, “but it feels like we’re all in this together, working to support the arts. I think that’s really special.”

“When the museum was dedicated in 1937, it was dedicated as a sanctuary of beauty and a temple of contemplation,” she says. “We want to be relevant in our community by tying into that idea of sanctuary and wellness and how we can use the museum as a tool for community wellness to help people when they’re going through difficult times and having mental health struggles. I personally believe that art is a powerful tool for healing, and I’ve found a lot of healing in art and in museums in my personal life.”