Brent Holmes finds kinship in the Barton Brothers, two early, unsung homesteaders to Nevada, through the shared experience of being Black in the American West.

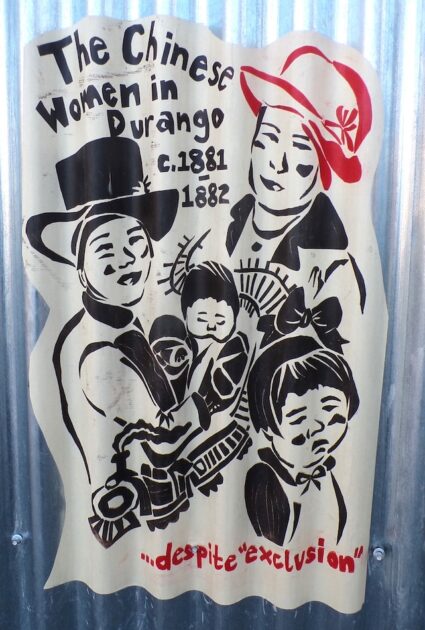

The history of Western expansion is lousy with tragedies, genocides, and exploitations of all kinds, yet it remains a pinnacle of American exceptionalism, an era that defines our ideals of individualism and freedom, and one of our culture’s sacred myths, for better or worse.

The Cowboy makes its nest at the heart of the myth of the pioneer West. The lives of Black women and men are still obscured in this era. The notion of pioneers of African descent engaging in the same settler colonial history as their European counterparts, endowed with similar freedoms and independence, still seems culturally foreign despite the many depictions and dense literature dedicated to their histories.

In the first few months of 2021, I was entrenched in my solo exhibition, Behold a Pale Horse, at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art in Las Vegas, Nevada. The work I produced included performative video and large-scale assemblage, concerning my personal and our cultural relationship with the Black cowboy.

Rebecca Snetselaar, the Nevada state folklorist (retired), reached out to me during my time exhibiting my excavations of the Black cowboy and informed me of a little-known piece of southern Nevada’s history in Lincoln County in the town of Caliente.

Before Caliente, Nevada, there was Lincoln County, before Lincoln County, there was Meadow Valley, where the first Mormon wagon trains arrived in the early 1860s. Before them, there were (still are) the Southern Paiutes. Prior to them, there was the pueblo-building, atrociously named Fremont people. Lincoln County was voted into existence in 1866, two years after Nevada itself was voted into statehood, in part to drum up votes for President Abraham Lincoln while annexing valuable mineral deposits away from the Mormon theocratic state of Utah. The earliest settlements in Lincoln County were made in Meadow Valley, a verdant swath of the Basin and Range Desert.

Nevada’s patch of the Basin and Range Desert is home to innumerable forms of life. Of the fauna, the most unique would be the pronghorn antelope, the fastest land animal in the United States. I’ve seen one from the passenger seat of an all-terrain vehicle a few miles from Michael Heizer’s City (1970-2022), running puffs of dust through sagebrush, outpacing our truck at dusk, its fur and the sky the same amber hue. The most dominant flora is the Juniperus osteosperma, or Utah Juniper. It scents the entirety of Meadow Valley: from Pioche through Cathedral Gorge and into the town of Caliente.

In 2020, I had journeyed to Caliente, predicated by a dream and a desire to perform video works at Cathedral Gorge. I’d grown attached to the region in previous visits, partially for its exuberant, lush beauty (partially because of the recurring dreams of crab people living in the cracks of Cathedral Gorge telling me to travel north to them!?), and partially for its rough weather-worn structures and decrepit mining haunts that I drew from for my assemblage work.

I’d built a small mythos around the importance of that region as foundational to southern Nevada and my identity as a Nevadan. So it felt serendipitous when Snetselaar told me what she was researching. She handed me a thick green binder and said something to the effect of: “Bruce Rettig [novelist and Lake Tahoe resident] had teased out these guys when he was doing some research for tourism, and he had put their names in as the first settlers of that area, and that’s how I found them…”

In the Bartons, I find my ancestry, not physiologically or even spiritually, but in the shared experience of being Black in the arid West.

The guys in question were Dow and Isaac Barton, two brothers crucial to Caliente’s inception and development. Yet they have no streets named for them, no plaques to their memory, not even a meandering hiking trail. They remained invisible for more than a century, due perhaps to a lack of community notoriety or wealth, but most likely because they were Black.

Querying how two Black men arrived in what was southern Nevada’s booming mining territory, surrounded by a mixed community of Mormon settlers and hungry prospectors, Snetselaar’s binder serves as a disparate narrative of their personal histories.

The United States census records the Bartons in Meadow Valley in 1864 during its first-ever survey of the region due to a mining strike. While the Civil War raged, the Bartons had settled a home distant from calamity in the high desert. A wagon train from the Utah territories had arrived a year or so earlier, after the discovery of silver in the area. Speculation would lead us to hitch the Bartons onto it, possibly as farm hands or teamsters. They must have been very different from the rest of the settler community, in many aspects. Keep in mind, slavery was still being practiced in towns like St George, Utah, and Overton, Nevada. So it is interesting that the Bartons are the only registered residents of what we now call Caliente. Most of their homesteading counterparts did not venture that far west.

Prior to 1864, Isaac Barton appears on another registry, thousands of miles away in Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1862 as a member of the first colored regiment’s muster roll. Were one to drizzle in a bit of conjecture, traveling to the unknown eremus of Nevada in the company of the nation’s most notorious religious sect may have proffered a better option than conscription into the looming civil conflict in the East. Even before that, Snetselaar speculates, their enslavement may have taken place in the Terre Noire region of Arkansas where she’s found slave-holding Bartons.

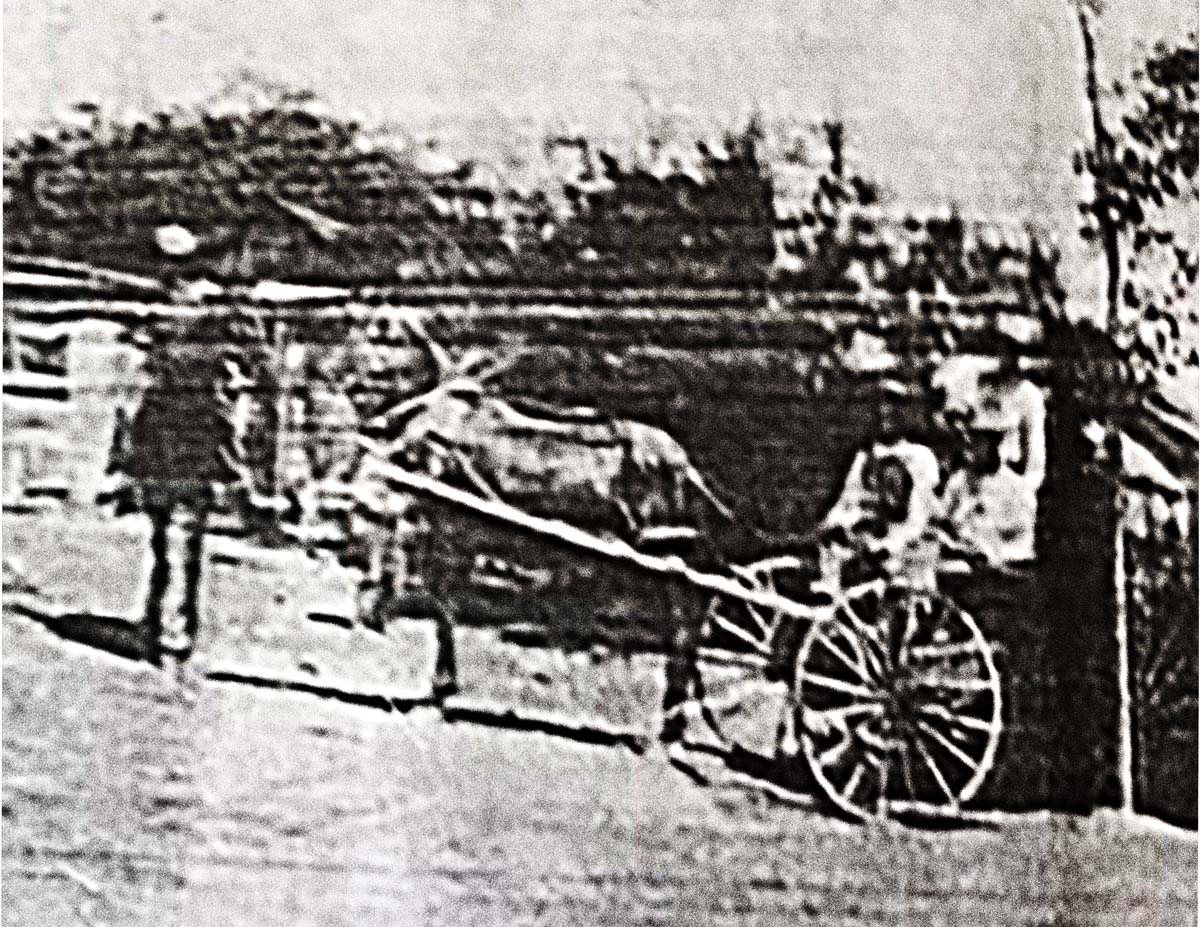

I received all of this information midway through my exhibition run. Snetselaar and her binder sent my imagination spiraling into speculative history. Pages of registries and property claims slowly gave way to highlighted news clippings. (I kept this folder for over a year after I received it, to Snetselaar’s chagrin.) Small details included Dow’s first wife filing for divorce in 1863 due to his year-long absence; Isaac bringing a cart full of Christmas turkeys to town in the Pioche record. The passing of Dow’s second wife due to colon cancer after treatment in Salt Lake. All provide small vignettes. And with gratitude to the Mormon methodology of record keeping, we have a first-hand description of the brothers which I provide to you in its entirety with the hope that it thrills you half as much as it thrills Snetselaar and myself:

Dow And Ike Barton

As told by Mariba Yoacham Singleton

Dow and Ike Barton were brothers. They took the name Barton from the man who owned them as slaves. Dow escaped from his master and went north and worked until he earned enough money to buy his brother Ike.

They came out west prior to the Civil War. They both owned property here. Ike owned property up the canyon from the Youth Center. Dow owned the property that was the southern part of Yoacham Ranch. Ike could read and write some, but Dow couldn’t do either.

They always had my dad buy their bib overalls. They always told him to get the biggest size in the store because all sizes cost the same. They would fold them over in front and tie them. They always wore rubber boots summer and winter.

They had a stove in their cabin with a door that opened in front. They would put a log in the stove and leave the stove door open. When the log would burn down, they would push it in again. One day they left the cabin and forgot to push the log in. It fell to the floor and burned their cabin down.

Dow’s eyesight became very bad and he couldn’t see to fix his fences and round up his cattle. Dad used to do this for him.

Dow had a kind and gentle disposition, but Ike wasn’t as pleasant. They moved to California around 1912, I think. I’m not sure of the date but it seems like that is the date my parents mentioned. Ike wrote a note to my grandmother after they moved to California, but that was the last time they heard from them.

The Bartons did not live lives of glinting adventure like Bass (Lone Ranger) Reeves, or filigreed daring like Nat (Deadwood Dick) Love. Those more renowned cowboys of color capture greater swaths of the public imagination. Still, the Bartons provide an insight into the Black experience before and after emancipation—another small refutation of the great white history of settler colonialism. They even cast their ballots in 1866 to establish Lincoln County, engaging in what would be forbidden to our people for a century. They left Caliente after selling their property to the Union Pacific Railroad and lived the rest of their lives in Riverside, California.

My work began to shift after 2021, still engrossed with the presence of Black people in the Manifest Destiny–era, but more speculative, less objective. There is one known image of the Barton brothers standing together with a horse and cart in their oversized overalls, shadow rendering their faces inscrutable. Snetselaar and the Bartons led me down a road that required imagining an ancestral Black West, a way to depict the thousands of Black lives that prevailed across this continent, barely recorded due to illiteracy and the bigotry that caused it.

When I think of them, I think of two men under desert skies, breathing in the scent of juniper, laboring as free men, their lives and property their own, a truer embodiment of America’s ideological freedom than any Clint Eastwood or John Wayne could ever stand proxy for.

When I think of them, I think of two men under desert skies, breathing in the scent of juniper, laboring as free men, their lives and property their own, a truer embodiment of America’s ideological freedom than any Clint Eastwood or John Wayne could ever stand proxy for.

In the Bartons, I find my ancestry, not physiologically or even spiritually, but in the shared experience of being Black in the arid West. Distant from the presumed identity of a people in constant reconstruction. I feel a kinship unmarred by time.

Although the construct of linear temporality is an effective method for stringing together a life, in actuality, human experience moves in simultaneous and divergent ways that make events and moments cumulative—a collection of experiences happening in the mind, and body, developed out of subjective histories in the moment all at once. This can be said of the African diaspora in particular.

To be Black, in America, is a rough and jagged path. Though no ethnicity can proclaim a purely progressive chronology, the lives of Black folk seem particularly fraught with retrogression, consistently buffeted by echoes of slavery and acts of persecution. Time and bigotry mute lives. We arrange events and individuals in order of prominence like dominoes to be toppled one after the other by a series of causal eventualities. When engaged in the study of the past, we rarely observe absences. The presence of individuals (no matter how mundane) like the Bartons provides a more complete understanding of our collective histories.