Tamarind Institute, Albuquerque

April 20–July 6, 2018

Paper has a memory. Each crease is recorded in the impression left where it was once folded. It can expand like origami, and it can collapse into flatness again, but its history remains pressed into the stuff it’s made of. It is this material and all the marks worn, pressed, and printed into it by careful hands that is on display in Two-fold: A Pairing of Frederick Hammersley + Matthew Shlian at the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque.

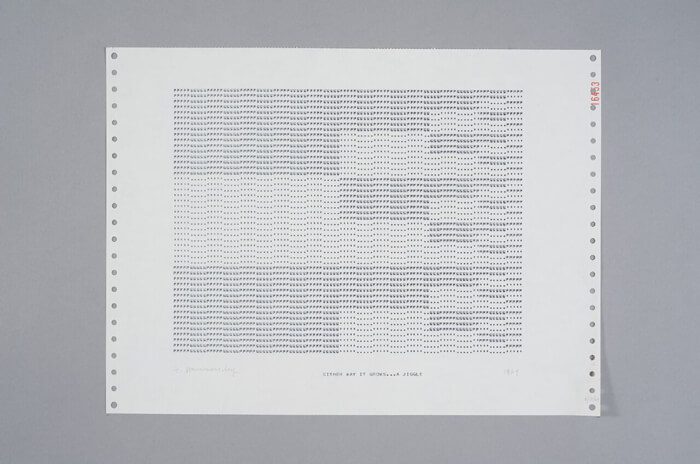

Here, two inventive minds are brought together for an exhibition that is—and this is not reductive, but high praise—flat-out fun to look at. Along the west wall of the small upstairs gallery at the esteemed lithography center, early works by famous American painter Frederick Hammersley are handsomely arranged. Inspired by an IBM mainframe computer that he encountered shortly after moving to Albuquerque, Hammersley began a series of images using letters and symbols from the basic keyboard. These geometric compositions are of subtle squares, diamonds, arches, and waves with all the hollows, hills, and calculated blank space of a topographic map.

The visuals here—and they show up in every piece in the show, Shlian’s work included—play with our perception. Unexpected symmetries take shape, sometimes only because our brain anticipates them, but upon closer examination we see all the nuance of the pattern. Here is work—much of which was made decades ago—that lives in the vanguard of art and science, combining to not just powerful, but objectively eye-pleasing, effect.

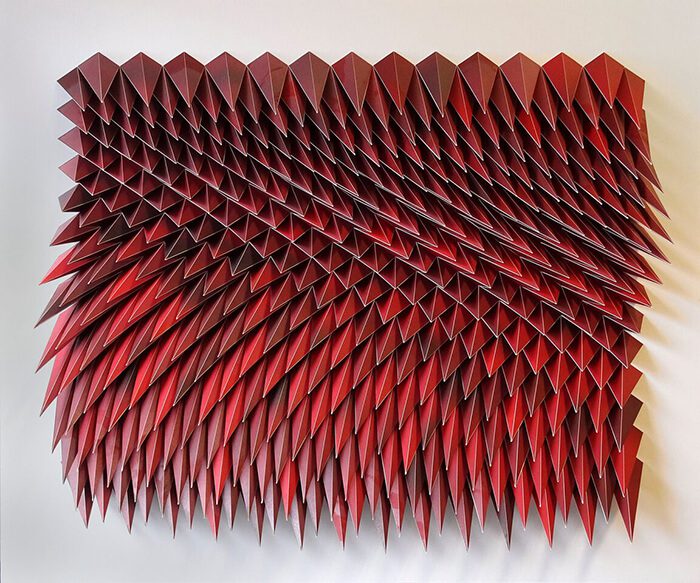

Shlian’s work in the gallery takes up equal amounts of space as Hammersley’s but has actual dimension, not just a Magic Eye–effect of depth. For that reason, they are perhaps more arresting. Both artists’ work can feel a bit remote—sterile, obscure science experiments that are not quite explicated. However, approaching means recognizing that these are all made of simple and familiar material—letters, as it were, for much of Hammersley’s, while Shlian works solely in that most ubiquitous, much trafficked human material: paper. (The Tamarind is, after all, dedicated to the art of lithography, so each artist’s work in the exhibition does, of course, lean on this particular way of printmaking.) And each of Shlian’s pieces is put together—cut, folded, and glued—by hand, adding something very human to the machine-like perfection of the finished pieces.

With the precision of a diamond cutter, Shlian practices his own unique brand of kirigami—a sort of praxis that incorporates the intricate folds of origami, plus cutting and gluing to create structures that would be impossible with folds alone. The end result is hard to put words to: they are tiled patterns, repeated planes and curves, tesselations of color and shape. Without making a choice—unconsciously, even—viewers can get lost in the sculptural, wall-hanging works. We are only snapped back into the gallery at the moment when the eye eventually wanders to the pleated edge and trails off into blank white walls.

Incidentally, Shlian was the first artist to receive the Frederick Hammersley Foundation Artist Residency at the Tamarind, so showing with the award’s namesake makes sense. Moreover, both artists explore depth and pattern and how those simple, basic artistic elements can become increasingly complex—can even satisfyingly form a core conceptual element in a body of artistic work. The topological splendors here are complex, but not necessarily complicated, offering us ways to experience the sometimes-overlooked joy of materiality. It is the composite wonder of a million small, iterative parts that turns us back on ourselves; viewing this work can be largely about our own perception.

In Two-fold, three-dimensionality is created out of two-dimensional materials. The way we anticipate mirroring and how our own complex, pattern-seeking minds search for sequence becomes apparent as we simply look outward. Each of us is in possession of our own unique algorithms for piecing together a visually complex world, and we all tend to bend toward symmetry and scope.

There is a long history of paper folding in material culture and geometric abstraction in painting, but this is something different. Two-fold propels us into modernity and speaks to the ways in which the arts and sciences shape and challenge each other. Both series are similarly virtuosic and methodical, delineating different, energizing modes of working within abstract art.

Through flat planes and hard clean lines, the artists explore new capabilities for works on paper. Sharp and exact as each piece in the exhibition is, they remain intuitive. Whether connected to an innate desire to parse out the language of mathematics or some deep memory of vital geometries, there is something familiar. Though scientific in their exactness, there is an intimate quality to them too, the recognizable human hand at work, deft and able to manufacture perfection—as perfect as anything ever gets. Here, both qualities once thought to be at odds—the exactness of science, the warmth of the handmade—are deftly typed, printed, and folded into singular works that are hard to sieve from memory.