Carried by the rails that their ancestors laid, rode, or resisted, nine artists challenge dominant histories of the Transcontinental Railroad in this multi-venue exhibition.

OGDEN—Conventional histories of the Transcontinental Railroad are speeding caravans of common themes such as American exceptionalism, economic power, ingenuity, and expansion. On May 10, 1869, Leland Stanford, co-founder of the Central Pacific Railroad, united the eastern and western sections of the railroad with a 17.6-karat gold spike. The joining of the rails was the culmination of work that began in 1863, laying track eastward from Sacramento, California, a project that employed over 15,000 laborers, 13,000 of whom were Chinese immigrants. A close examination of photographs by Andrew J. Russell, who documented the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Point in Utah reveals that the Chinese workers were pushed to the periphery that day. Russell quite literally cropped them out of visual history.

In The Other Side of the Tracks, opening at Ogden Contemporary Arts on May 3 and subsequently traveling across the Southwest, curator and artist Jorge Rojas widens the frame on dominant narratives he observed during the 2019 celebration of the Transcontinental Railroad’s 150th anniversary. His curatorial vision is inspired by the lives most directly affected by the railroad’s construction: enslaved African men and women whose labor built the railroad and the economy of the South; the Arapahoe, Sioux, and Cheyenne, whose ancestral lands were seized and cut through to create thousands of miles of track; and immigrants from Ireland, Mexico, and China, who installed the tracks and died by the hundreds from disease or exhaustion throughout the process.

This multidisciplinary exhibition highlights the work of nationally and internationally recognized contemporary artists who come from these historically marginalized communities, their voices excluded from the triumphant tales of the track. The artwork of Native American, African American, Chinese American, and Mexican artists conjure a powerful vision of the railroad that offers a more holistic understanding of all that went into such an ambitious and hard-won accomplishment that continues to benefit so many American lives today.

The nine exhibiting artists, each with an ancestral lineage that is linked to the railroad, are Tania Candiani, Raven Chacon, Gregg Deal, Guillermo Galindo, Zhi Lin, Caroline Liu, Paisley Rekdal, Xaviera Simmons, and Chip Thomas. The Other Side of the Tracks debuts at OCA (May 3-July 14, 2024) and then travels to RedLine Contemporary Art Center (August 16-October 6, 2024) in Denver and 516 Arts (November 9, 2024-February 8, 2025) in Albuquerque.

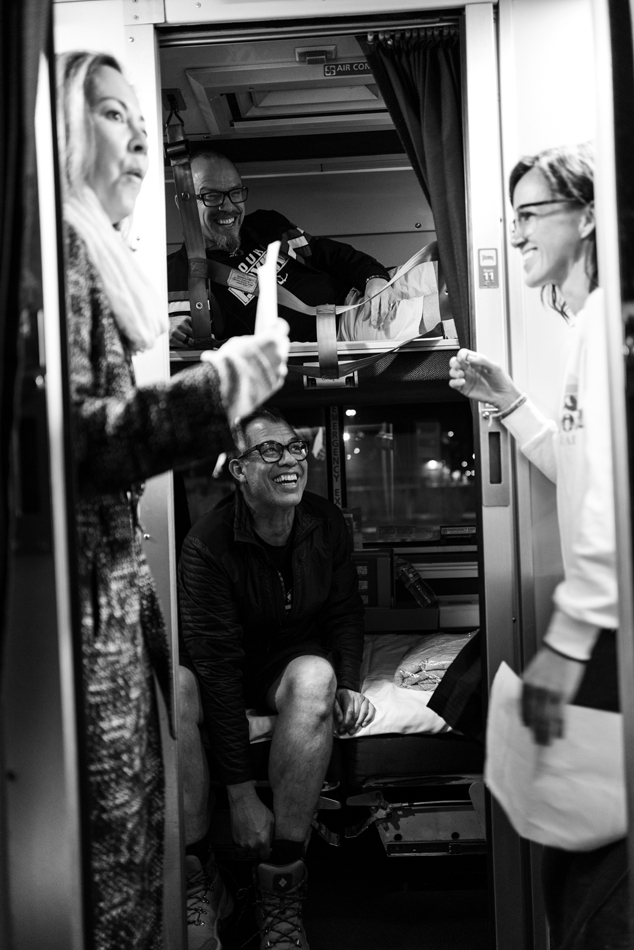

A crucial component of the project was a mobile research expedition, a seven-day train journey from Denver, Colorado to Sacramento, California that was organized by Rojas and unfolded in October 2023. The group included seven of the artists, the curator, two writers, a photographer, a videographer, an intersectionality theory expert and at least one representative from the three presenting institutions. The research dynamically informed the production of works for the exhibition, and the adventure sparked provocative dialogue, the gathering of rich sensory information, intimate collaboration, and the deep connections that traveling together in this way can inspire.

The group visited important historical sites and museums, and communed with various experts, historians and tribal leaders. Ultimately, it was the somatic experience of feeling the train’s unrelenting rhythms for an extended period, as the artists’ bodies and psyches passed through thousands of miles of land where their ancestors had moved, labored, and often suffered, that led to the fascinating results of this materially and conceptually rich exhibition.

As a new generation of faster trains emerges it is important that we think critically about the history of our railways: who they’ve served, who they’ve neglected, and who they’ve hurt.

Tania Candiani’s textile installation Modesta Ávila is a stunning tribute to the Mexican American folk heroine and activist. Ávila’s infamous mugshot is meticulously stitched on canvas with cascading black threads, capturing her brazen defiance as the railway and countless laborers tore through the land she’d inherited from her mother. Tracks for the Santa Fe Railway were laid approximately fifteen feet from the door of her home. She was arrested for obstructing the railway with a clothesline, which Candiani recreates in front of Ávila’s portrait, stringing up hand-stitched cotton banners that boldly spell out Esta Tierra Me Pertenece (This Land Belongs To Me). Ávila demanded $10,000 in compensation that she never received. In fact, she paid a very high price for her resistance. While serving a three-year sentence in San Quentin prison, she died of a fever in her mid-twenties, never returning to her land.

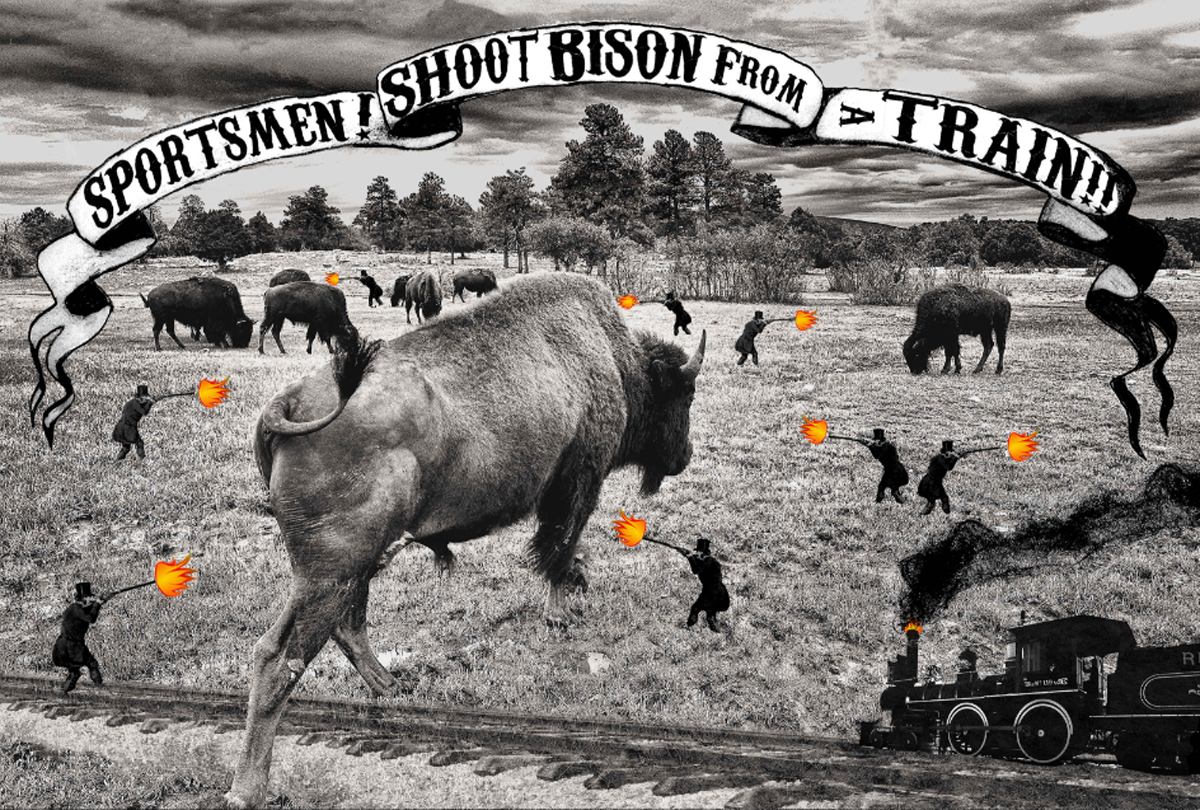

Chip Thomas’s The Bison Didn’t Cross the Tracks, The Tracks Crossed the Bison is a large format photograph printed on translucent silk that will hang in OCA’s expansive front windows. Thomas depicts white hunters recklessly shooting at bison as a locomotive speeds through the Great Plains. The image refers to an 1867 quote by General William Tecumseh Sherman to Major Philip Sheridan: “Native Americans would never give up their lifestyle until the buffalo are gone. I think it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America there this fall for a Grand Buffalo hunt and make one grand sweep of them all.” The Plains tribes relied upon bison for clothing, shelter, and food, so this government-endorsed slaughter, which averaged 5,000 animals per day by the 1870s, mercilessly targeted Native people and their cultures.

Experimental composers Guillermo Galindo and Raven Chacon explore the hobo culture that flourished on the railways in the 1890s. The hobos were itinerant workers that roamed the country by train. It’s impossible to determine how many there were as part of their intentional lifestyle included jumping trains and traveling in ways that avoided detection. These drifters weren’t always welcome, so they built an elaborate code system—symbols left on fence posts, mailboxes, or trees that told other hobos what to expect in the town or from nearby landholders. Knowing where to go and whom to avoid was vital to these travelers.

Galindo and Chacon collaborated on Caesura, a performance piece using a call-and-response method that incorporates these surreptitious symbols, some of which are depicted in an accompanying written score. The symbols are inserted as notations for performers’ movements between instruments, becoming a language of nomadic sound. A performance of Caesura, titled after the musical term for a pause in the flow of sound, is scheduled for July 12 in Ogden and will acknowledge the many communities that were shaped, transported, and left behind by the train tracks.

In considering the tremendously captivating, and no longer forgotten, perspectives brought forth in videos, photography, textiles, poetry, sculpture, and sound by this formidable group of artists, Jorge Rojas reflects, “As a new generation of faster trains emerges it is important that we think critically about the history of our railways: who they’ve served, who they’ve neglected, and who they’ve hurt. The power that trains have to move and inspire us is still strong; but if we are to build a more equitable future, we must make a more concerted effort to clearly see our past.”