Raven Chacon runs a record label, is a member of multiple bands and collaborative projects, teaches teenagers experimental composition, and is currently included in SITE Santa Fe’s recently opened biennial, much wider than a line (through January 8, 2017). Born in Fort Defiance, Arizona, and educated at UNM Albuquerque and California Institute of the Arts, Chacon calls Albuquerque home. However, the city is not always the location of his studio. Conveniently for us, Chacon brought his studio to THE for our recent interview. As a musician, sound artist, and ardent collaborator, Chacon’s flexible studio practice reflects the versatility of his work. Currently, he is writing a composition to be played by the renowned Kronos Quartet at Carnegie Hall in 2017 alongside compositions by Laurie Anderson, Philip Glass, and others.

Clayton Porter: You know, typically we want our studio visit to be where we actually visit the studio and talk predominantly about studio practice.

Raven Chacon: Yeah… See, when I was putting up the UNM show (Lightning Speak: Solo and Collaborative Work of Raven Chacon, 2016, UNM Art Museum), I had a really nice studio; I only rented it until I was putting that show up. Then I moved into a small cubicle. It’s just wires everywhere. It’s not very interesting.

CP: As a sound artist, how important is a studio? How important is a space for you?

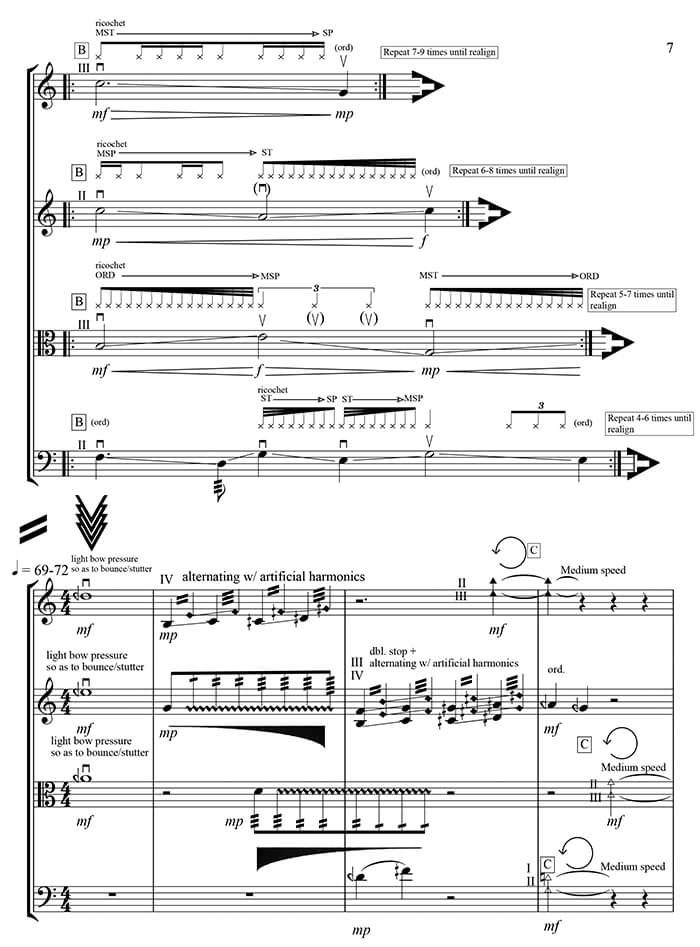

It could be very important. It could be nice to have a large space to be able to run cables. And as you saw in my show, it is nice to set up some more sculptural installation work, where you might have to gauge what sounds might be like in a space. That would be one extreme. The other end is just needing headphones or two monitors to listen to music, make music… Or just a desk. Right now I’ve been working on a commission for Kronos Quartet, and I’ve been just sitting at a desk, writing on some paper. That’s really what I’ve been doing for the past two months. I haven’t needed anything. Just a desk, a pot of coffee, stack of paper.

CP: Are you looking for a space now?

Postcommodity [interdisciplinary arts collective, Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez, Kade L. Twist] had Spirit Abuse for about two years. It was Postcommodity’s studio in Albuquerque, but for the past eight years or so I’ve been involved in DIY venues in Albuquerque, so it kind of functioned as both. We’d use it to stage some of our more sculptural works that we were working on, and then,at the same time, use the opportunity to exhibit video art. Different artist friends from all over— artists from Canada, California, an artist from New Zealand—would Dropbox us over a video, and once a month we’d show this video work. Once or twice a month we’d have concerts, experimental music concerts. But we closed it down to save money for the Fence project [Repellent Fence, 2015], because we needed to buy helium, so we needed every cent we could save. It’s still an ongoing project; it just doesn’t have a physical space right now.

CP: Why Albuquerque? Why New Mexico?

Well, I’m pretty much from Albuquerque. I grew up on the Navajo Reservation, but my father is from Mora, northern New Mexico, and the family moved out here when I was about eight or nine. I’ve lived in Albuquerque pretty much my whole life. I lived in Los Angeles for a while, but I moved back. I think Albuquerque has a great music scene, and that’s what I do. Anything from experimental, noise, rock, DIY spaces, to all kinds of bars and venues all up and down Route 66. There’s no shortage of live music happening in Albuquerque. What Albuquerque lacks is the kind of visual art presence that Santa Fe has. So, between the two, there are great things happening. The cost of living is very inexpensive. And the people. I like the types of minds that reside in New Mexico, the type of art that the people make.

CP: Are you performing on a regular basis?

I’d say ninety percent of what I do is all performing- and music-related. I’m involved in five or six bands, separate from Postcommodity, although Postcommodity makes music also. I’m involved in a few different collaborations, with people in Albuquerque, with people in New York, and performing and recording is a big part of what I do. I also run a label, called Sicksicksick Distro, and I release music from all kinds of musicians, all over the region. I’m hand-making a lot of those projects, folding records together or cassettes, mixing or producing albums for the musicians, and I do all that in my studio.

Lauren Tresp: What are your day-to-day hours? Is it always different, because your studio is always different?

When I’m traveling with Postcommodity, we generally keep somewhat nine-to-five hours, because we’re a group and we have to set hours to work together. If I’m working alone, I do a lot of work midnight to four, five a.m. Personal time is in the afternoon. A lot of work is rehearsing with other musicians. Death Convention Singers—a group of twenty or so musicians from Santa Fe, Albuquerque, all different kinds of characters—did a performance last summer at MoCNA, we had a cart and water from the Animas river, that orange water. To rehearse something like that you’ve got to find whenever twenty people can meet. So I have to be flexible.

LT: How do you find your solo practice to be different from working collaboratively?

I could see some solo artists never knowing when the thing is finished, when it’s done. With collaboration, everybody’s going to decide it’s done. I think for me, I try not to get in the trap of being unsure of what the piece is. Because—maybe this is because I come from a background of improvised music—a piece could take on other versions. . . or maybe it is never done, in some ways. For instance, when I did the bird cage piece [While Contemplating Their Fate in The Stars, The Twins Surround The Enemy, 2003], that was the second time I had done that piece.

I did it first in Los Angeles. When I did it here, my wife Candice contributed a piece of text from a book that was put on the wall to go with it. So pieces can constantly shift, or morph, or take on new forms. I think I’m not so permanent about what these things are sometimes, and I think that helps when making work as a solo artist. I’m not set that it has to always be a certain way. It can be an improvisation. It can be the same piece in different forms—a different medium even.

LT: Humor me, because sound art is something I’m not very familiar with, but how did you come to sound art?

It’s kind of a funny thing. I didn’t know what sound art was, either. I came about it from being a musician and realizing that there are other ways to present music or sound. And realizing as an artist that sound art can take on the form of video: what appears to be a video work actually had more prominent sound than visuals, for instance. Or you have a sculpture that produces sound. My entry point was just being a musician… I formed a band when I was sixteen or seventeen. We didn’t have a place to play, so we’d go play out in the desert with a generator, or whatever. Everybody had the worst instruments. Guitars with, like, two strings; amplifiers with the speaker sliced open. And the only people I could find couldn’t play. They sucked. So that was the band: it just sounded like noise. I got used to playing with people like that. (Laughs) It was not ideal music. Trying to make it sound like Slayer or something, but it sounded like noise.

It informed what I realized music could be. At the same time I also had studied the piano with a piano teacher, knew how to read music, and was interested in composing real music. I had these two sides, and they somehow came together, especially when I went to UNM and started studying with music teachers there and learned about twentieth-century music, and John Cage, and all that. I realized that that’s the kind of music I want to make. Still, for me it ended up on stage, or in a recording. It wasn’t until I moved to Los Angeles that I became more aware of what other artists were doing, having installations. I was learning what sound art was. And even still, I was always just interested in making music, probably up until I joined Postcommodity, and then I started thinking, well, what can I lend to this group? What can I offer to these guys who collaborate in this group? What perspective on sound? These guys were making video; I might see time or linearity in a different way than these guys might.

LT: Can you tell us about the project at SITE? [Native American Composers Apprenticeship Project, 2004-present]

Another large part of work that I do is teaching young people. I’m not a full-time teacher or anything, but I do this program on the reservations—the Navajo Reservation, the Hopi Reservation, the Salt River Pima community—where I go for a week into each of the schools and find five or six students, thirteen years old to eighteen years old, and give them the task of writing a threeminute string quartet. Some of these students have band or orchestra class, so they know how to read music. Some of the schools don’t have any of that, so I have to show them—very quickly, in a day—how to read and write music. I teach them everything I can about how to play the violin or the techniques you use for a cello, viola, or violin. I don’t play those instruments, but I can demonstrate enough how to make sounds, how to make music. And the students have a week to write these things out. On Labor Day weekend we put on a big concert at the Grand Canyon, and a professional string quartet comes from New York City (ETHEL, Catalyst Quartet) and plays these compositions. At SITE, there are listening booths of some of these students’ work from the past twelve years that I’ve been doing this program, six really avant-garde pieces from these kids. In addition to that, I’ll be working with some students from the Santa Fe Indian School, and they’re going to write some new pieces. Two years ago NPR Performance Today did a story on it. They actually made this website that documents the work we did (performancetoday.atavist.com/voices-that-need-to-be-heard).

CP: I remember seeing for the first time your bird piece at the AHA fest. It was simple and very present; there was no clutter. I even remember looking around like, “Where’s the art at? Who is this?” There were no tags. It was so pleasing to think that you weren’t just standing there in front of your piece, like most people do, seeking attention.

Yeah, I would’ve left it up and just left, but people were getting angry at this piece. There were two birds and this kind of piercing tone, but the amplifier was nowhere near the birds. It was in the corner. It was quiet; it wasn’t very loud, but people were so angry. They were accusing me of harming the birds. People were actually tampering with the piece. They were unplugging the amplifier; somebody hit it. I thought somebody was going to let the birds free. One guy, like a hippie guy, tie-dye everything—I think he wanted to fight me. I just said, “Don’t touch the work.” It got confrontational. That was the only reason I actually stuck around.

CP: Do you consider your works confrontational, or do you think they have confrontational elements?

I think they can. I think noise, the very nature of presenting noise, is going to be confrontational with some people. It’s not my intention to be obnoxious, by any means, but—as far as the sonority of the sounds I like to make—I think those can be confrontational. They at least set up a line, saying either you’re really going to hate this, or you’re going to start to get over on this side and see what this is about. I think the tonalities and the sounds that I’m interested in making force that line to happen. I think that sound has that power more than anything, because—well, film probably does, too—but I think there are a lot of assumptions about what sound is going to be or what music is going to provide— especially if it’s accompanying something else. I can hear an opera singer, an aria or something: I know that I’m going to expect something out of this before I encounter it. From its first note, I know what it might be.

There was another Death Convention Singers situation, where I sent an email to five core people of the group and said, “Forward this email on to other musicians in Albuquerque. Don’t mass-do it; do it individually, and don’t tell anybody else who you’re sending it to. Tell them to meet at this location at midnight, on this date, and bring an acoustic instrument. It’ll be pitch black when you arrive, bring a flashlight if you need, or just be careful. And don’t talk to anybody.” I would go ahead of time and set up recording mics and whatnot and just sit in the dark and wait for people to show up. I’d sometimes have a guitar with me or just my voice. One location had a piano inside of it. People would show up and play together. I don’t know who’s on the recording. For some, thirty people showed up. For one, there were only three. But I don’t know who they were. We made a whole album anonymously [Brujas, 2008]. I know that the five people who I initially emailed are on it somewhere, but otherwise I don’t know who’s on the recording. It resulted in a CD; they’re all sold out, but it’s on Bandcamp now [deathconventionsingers.bandcamp.com/ album/brujas].

So these are the kind of—I don’t want to use the word “community actions” because that sounds too lame—things I’m just doing in Albuquerque. Creepy things, kind of.