Medical doctor, photographer, and public artist Chip Thomas has taken a historical turn in his work, building on deep, place-based research and activating architecture with archival discoveries.

Flagstaff, Arizona | jetsonorama.net | @jetsonorama

When Dr. James “Chip” Thomas, Jr. first started his medical residency, he’d take regular excursions to New York City. It was the early 1980s and Beat Street had just come out, Keith Haring’s Pop Shop was open, and the city’s subway trains were adorned with massive spray-painted messages, a moving roll-call of artists from the margins, participating in an explosive new public art. “My love was always for street art,” Thomas says.

His other love was photography. After establishing his medical practice on the Navajo Nation in 1987, he built a darkroom to develop the portraits and documentary photographs he was taking of his adopted community. Blending both of these passions, in 2009, Thomas began wheat-pasting black-and-white photographs on walls in the midst of a global street art renaissance fueled by the internet and a nascent social media. He worked under the playful moniker of Jetsonorama and initiated the Painted Desert Project to bring street artists and muralists to the Navajo Nation.

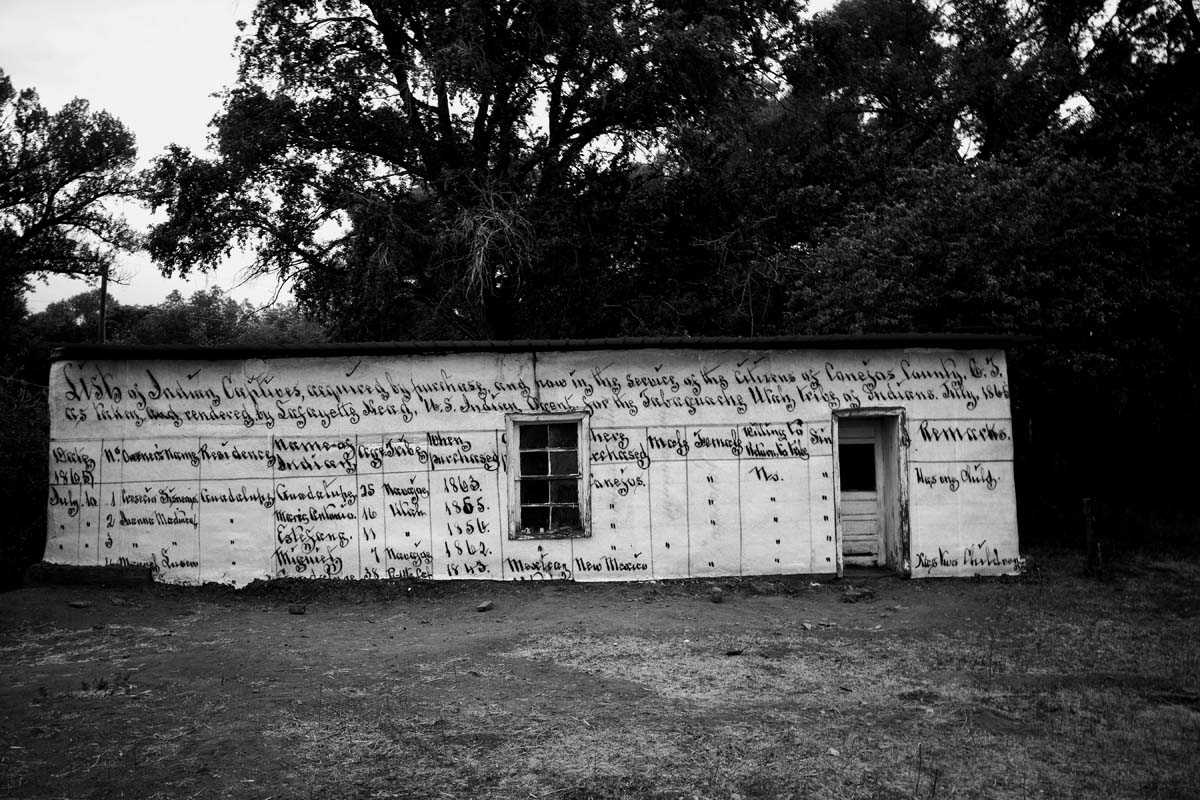

In recent years, Thomas’s work has taken a historical turn, combining deep, place-based research and activating architecture with archival discoveries. “A lot of these historical projects have been passion projects, where I’m learning histories that are relevant to me as a person of color here in the Southwest,” he says.

With Thomas’s work, viewers will often encounter these histories in enlarged photographs on the very walls where the depicted people lived and breathed—a site-specific interaction of history, image, and architecture.

In foregrounding stories of individuals in the Southwest from marginalized communities, Thomas’s works help supplant entrenched narratives, sometimes quite literally. His 2021 installation at Fort Garland, Colorado, addressed the long-overlooked history of Native enslavement, taking the place of a problematic paean to Kit Carson that had been on display at the museum for nearly seven decades.

“I see myself as a visual storyteller,” Thomas tells me. These stories—of people like Charlie Glass, a legendary Black cowboy who made his name in Moab, Utah; of John Taylor, formerly enslaved Buffalo Soldier who was the first non-Native settler in what is now Durango, Colorado; of former uranium miners on the Navajo Nation like Harvey Speck and Kee John whom the U.S. Public Health Service did not warn of the dangers of breathing radioactive dust on the job for many years—tell a history of the Southwest not widely encountered. In Thomas’s work, their voices echo out from the walls.