Artists Patrick Nagatani, Richard Tuttle, Esteban Cabeza de Baca, and Lucy Raven attest to the nature of the poetics of place through artworks centered on the New Mexican landscape.

I am not in New Mexico. But I am there. If I close my eyes I can see the snow-capped Sangre de Cristo mountains and the pueblo beneath it or the juniper- and cacti-dotted desert severed by I-25, and the random ocotillo snaking up above the rocks and tapering into pink tongues. If I think of it, I can smell the roasting chile and the burning piñon. Wherever I am, I am in the Jemez or Chama, or White Sands or in the foothills of Albuquerque or the city in the sky that is Acoma Pueblo.

For me, the call of New Mexico is deep and even though I write this from across the country, I feel as if I am there because the place has rooted itself in me. What is place, after all? The word comes from the Latin platea meaning “courtyard, open space” and “broad way, avenue,” and further from the Greek plateia (hodos) “broad (way).” So place is a designated location where one spreads out, expanding in all directions. Place is also a site that works on a person, growing in them rhizomatically. And one’s “internal place” is formed by the external—land, culture, history, climate, temporality, ecology, and so on—and that is filtered by sensory perception. The internal place roots us to the ground even when we leave for another place. It must be said that there is no place without poetics and they both meet in consciousness through perception and are exercised through poesis, that is “making and its processes.” The work of Esteban Cabeza de Baca, Richard Tuttle, Patrick Nagatani, and Lucy Raven, among many others attests to the pull that place has on an artist.

“Place is a designated location where one spreads out, expanding in all directions. Place is also a site that works on a person, growing in them rhizomatically.”

To live in New Mexico is to become a part of its geography and history. The state—that unnaturally squared imaginary boundary—includes mountainous regions, valleys and canyons, forests, prairies, rivers, and everything in between. It has white sands and red clay. It bears the marks of an ancient geology including dormant volcanoes and deep caverns. The state’s cultural history is ancient too, both visibly and invisibly, but dispersed, reduced, or erased due to Colonialism, Militarism, Christianity, and Capitalism. It is a place that teaches one to see because it demands it, to see its long history to the presence of the now. Abstraction and boredom are a part of life in the high desert too. It is as inescapable as the “operatic drama”1 that unfolds through storms and vistas. Its ecosystems are wildly diverse and one must be perceptive to really sense it all. Its people are often kind, thoughtful, and full of resistance to authoritarian powers. Yet, violence and death are as commonplace as the dry heat, and local cultures and their lands are often marginalized and treated as products to consume.2 This is to say, the place that is New Mexico forces one to understand life as a hybrid collectif, that none of us exists in isolation but rather within a series of complex relationships between humans, non-humans, and objects across space and time.3

In 2013, the residents of Mora County, New Mexico successfully passed an ordinance to prohibit all oil and gas drilling, most notably the process of hydraulic fracturing or “fracking.” It was the first county in the U.S. to pass such a ban and did so by stripping “the legal personhood of corporations.”4 The residents fought off these corporate “persons” with a belief in la Querencia de La Tierra or the Love of the Earth, an old Spanish phrase that has meaning throughout New Mexico. To see the land this way one must understand it as having various layers, histories, and temporalities, as artist Esteban Cabeza de Baca does. In his painting How Mora, New Mexico banned fracking (2022), the viewer is confronted with a vigorous composition complete with pine-covered hills and snowy mountains, vermillion- and sienna-colored rock formations and views, and light blue and azure-toned skies. For him, New Mexico is a place where “serenity opens beyond scale,”5 wind gusts speak in the voices of his ancestors, and views are neither singular nor concretized. We can see this in the strata of his canvases.

Like Cabeza de Baca, Richard Tuttle splits his time between New Mexico and New York (among other places). In his series from the late 1990s, entitled New Mexico, New York, the phenomenological effect the land of enchantment has on one’s life emanates clearly, despite Tuttle’s minimalism. See New Mexico, New York, D, #13 (1998), for instance. An irregular rectangle made of plywood serves as the base for a play between two tones, sage and juniper. It is easy for me to see the piece as a topographic map depicting several buildings and a river overlaying a canyon between two mesas. The painted shapes intersect (the juniper under the sage) and appear to float on the surface of the plywood. The logic of it as a map or landscape is betrayed by the overlaying of shapes and forms (how can a river flow along a cliff at its top and bottom?), but perhaps this is because it represents a map of a history, showing us multiple temporalities at once?

The tactile is evident in Tuttle and Cabeza de Baca’s work, drawn from the very source of experience one routinely has in New Mexico. And one never forgets the physicalness of a landscape. This is because land always works on us, because we are a part of it, like plants, rocks, and non-human animals. We cannot divorce place from nature any more than we can divorce ourselves from it. In Cabeza de Baca’s painting Besar La Tierra (2021), one sees both love of the earth and acknowledgement of our symbiotic relationship to nature en masse. Here two different New Mexican vistas bracket an outstretched torso. Around and through the body are depictions of trees, cactuses, flowers, and root systems. These images blend into and out of the torso, over and through which the artist has painted a spiral, a motif Cabeza de Baca has used throughout his oeuvre, pulled from pre-Columbian uses of the symbol. The composition wavers between surface and window, abstraction and representation, pointing to the artist’s embrace of several temporalities as a way to resist the ideologies that have “place[d] us on our knees” as an “historically colonized community,” as John Olivas, former chairman of the Mora County Board of County Commissioners, wrote in response to the corporate attacks on his own querencia.6

Trace—that is the concept whereby a thing’s presence is known by a mark it has made—undoubtedly impacts us in this process. Trace is a mark, like a brush stroke, a photograph, a footprint in the dirt, a petroglyph. It is like scars to trauma or smoke to fire. Traces blanket the landscape, as absences which then instill in us a presence; history bound up in the now. Patrick Nagatani’s Nuclear Enchantment exhibits the artist’s pull to the New Mexican desert where history collided with his identity as a Japanese-American. We of course do not see reddened skies or uranium-soaked landscapes when we visit the Trinity site. Nor do we see groups of Japanese tourists carrying plastic missiles to the great Nike-Hercules Missile Monument like the pilgrimages of devotees bringing little Buddhas to the Big Buddha. The artist shows us the absurdities in this landscape that although not always visible, are nonetheless there, so that we may see what is in fact the landscape, and that includes possibilities of the future.

In the winter, the high-desert light is often blue with a tinge of magenta and so it is in Nagatani’s photograph titled B-36/Mark 17 H-Bomb Accident (May 22, 1957), 5 1/2 Miles So. of Gibson Blvd., Albuquerque, New Mexico (1991). The image depicts a cloaked figure holding a photograph in a snowy scene. The internal photograph contains three people looking back at us as if we’ve disrupted them, two photographers taking photographs of a family and a nude woman, and a strange green patch of foliage bracketed by two figures over which a bomber flies. It is a classic Nagatani photograph, showing the viewer what is, what has been, and what could be. This scene references the accidental dropping of an H-Bomb by a B-36 Mark 17 Bomber in 1957. The bomb detonated leaving a twenty-five-foot crater. Luckily, the nuclear trigger had not been installed. Nagatani warns of a nuclear winter and reminds us that a militarized and romanticized landscape, as is the Western tradition, has consequences.

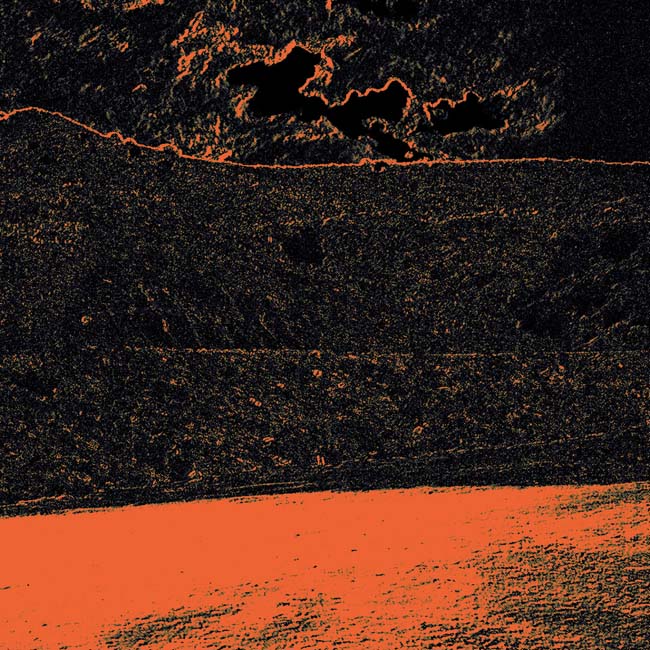

The unseen is also investigated by Lucy Raven in her recent video works Demolition of a Wall (Albums 1 and 2) (2022).7 Each album is exhibited on a large, squared screen overlayed with ambient and minimal sound by Deantoni Parks. The works depict a New Mexican landscape that is used as an explosives range by the U.S. Departments of Defense and Energy as well as private companies. Raven’s dominant focus though is not the explosion itself but rather what it causes: a shockwave. Album 1 is presented in the colors of the high desert, scenes that mimic one looking out across the land. A boom and flash of light disrupts the view and slowly an invisible line moves its way across the scene like a wave, swiping the image to another just like it. Album 2 begins with a view of the land in black and white. Again a boom, but here the screen cuts from extremely bright back to the same scene rendered into its most basic structure, one that highlights the particles that make it up. A bright line followed by its gradient slowly travels across the image. In one particular scene, the line is curved like a dome and creeps across the land, bathing the scene in a toxic orange that begins to almost quake. How can one not think of an atomic blast? These shockwave images seem as crude as some of the very first photographs made, a wonderful juxtaposition to the luscious black-and-white images seen before the blasts. In these works, the landscape is born anew, albeit under an ominous view, glowing like a nuclear landscape being read by some futuristic device or simply revealing an invisibility that propels along unseen. Raven shows us the traces, the subtleties, and the existence of information beyond the visible spectrum, so that we may know our impact on the land and that greater forces than us are always at play.

We see the land from our own eyes, from the human perspective, but it isn’t just “outward,” but upward, downward, through, in, outside of, and beyond. For all of these artists, the visible and invisible come together through matter of making and speak to the dynamics of the place that is New Mexico, which in turn speaks to all, cosmically. History, ecology, land, identity are all swirling about one another in the now, leaving traces in our internal places. We carry the place, a good place, with us in perpetuity.

1. Rebecca Solnit, “The Red Lands” in Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics, Oakland: University of California Press, 2008, p.16.

2. Chris Wilson wrote in his book The Myth of Santa Fe that the “trivialization of local cultures into tourist clichés and their denigration as second-rate by cosmopolitan intellectuals must be contested at every turn.”

3. Michael Callon and John Law, “Agency and the Hybrid Collectif”, South Atlantic Quarterly 94 (1997), p. 481-507. Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves, Oakland: University of California Press, 2015, p. 39-42 and 213-14.

4. Simon Davis-Cohen, “Why Are Fracking Hopefuls Suing a County in New Mexico?” The Nation, 29 June 2015.

5. Colin Edgington and Esteban Cabeza de Baca, “Esteban Cabeza De Baca with Colin Edgington,” The Brooklyn Rail, 29 April 2022.

6. John Olivas, “The Truth behind Fracking and Mora County,” Santa Fe New Mexican, 29 May 2018.

7. Raven’s piece takes its name from Louis Lumière’s Demolition of a Wall (1896), the first moving-image film to show motion in reverse. For Raven, this was a jumping-off point, less about reversal of motion and “more about how something that happens in the past can mark a pivot point in forward action.” Private email exchange.

Nike-Hercules Missile Monument, St. Augustine Pass, Highway 70, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, 1989 and 1993. Copyright Patrick Nagatani. Courtesy Andrew Smith Gallery, Tucson.