Grace Rosario Perkins describes a drawing she had made years ago, taking Black Flag’s Family Man album and replacing Raymond Pettibon’s violent imagery with a repeated series of pencil drawings of women. She then filled out the liner notes with her mother’s name, whom she credited with everything from production to bass to vocals. “I want to start a punk band with my mom,” she said, one of dozens of brilliant ideas she mentioned offhand over the course of a conversation in her East Downtown studio in Albuquerque.

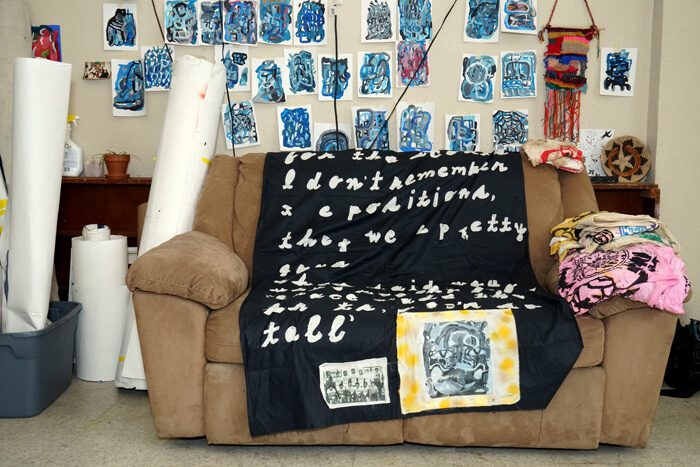

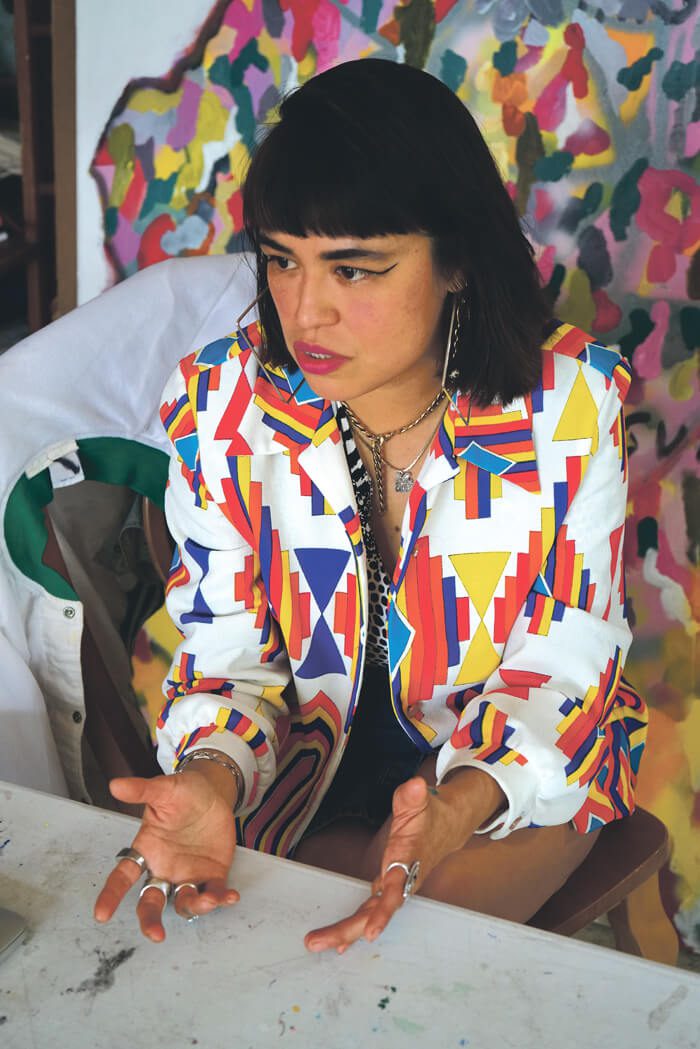

Inside, the bones of an old bookstore that used to occupy this space have been repurposed, tubes of paint stacked in the grooves that were display shelves. Perkins’s large-scale paintings, vibrant and dense, cover a large plaster wall or lean on an old love seat centered beneath the window, where the muted sunlight of an unusually gray day filters in. She’s been in this space since last May, when she returned to New Mexico after a long time spent in the Bay Area. Though she largely grew up in Santa Fe, the Diné and Akimel O’odham artist bounced all over the Southwest before living in Oakland.

In her work, which takes shape in many media, not just on canvas, Perkins explores vast themes. Sports, punk, what it means to center Indigenous women in those arenas, legacy, landscape, language—they’re all crowded, stratified as layers of paint onto the physical objects that become their expression.

She recalls a friend coming to visit her studio and observing that her work is incredibly convoluted. “But he didn’t mean that in a bad way,” she explains. “He saw how every subject and emotion is shoved into the surface. When he said that and I thought about who I am as an Indigenous person, as a young person, as a contemporary person—my experience has never been really clean.”

Now with several books to her credit, numerous exhibitions past and upcoming, residencies, and even fashion shows in the works, she remains invested in the work itself. From early years painting in her bedroom and scanning her work to post on Tumblr, she’s always thrown herself into the act of creation. “Humans are creators,” she says. “It comes with the territory—it’s survival.”

Maggie Grimason: When did you begin accessing art and thinking about it as a life path for you?

Grace Rosario Perkins: My dad’s an artist. My uncle runs a print shop in Santa Fe. My whole life, I’ve been around artists. Ever since I was little, I was given a pencil. It wasn’t until I was in Oakland and I started teaching art to adults with disabilities that I got these more radical ideas about the way that you can create. I worked at every art center in the Bay, but I worked at one called Creativity Explored, and there were a few painters there that I watched. And I remember having this “aha” moment about painting, and that’s when I started doing it more seriously.

Was there something that you observed there that moved you?

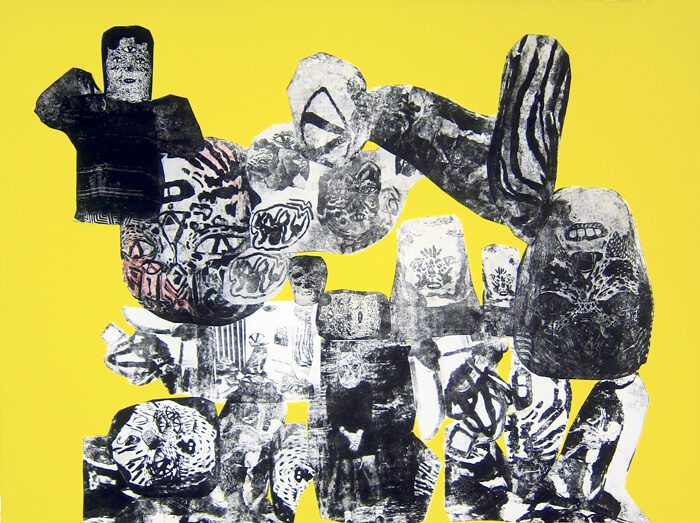

I watched a woman—her name is Marilyn Wong. She was so influential to me. I was always really fascinated by her process: it’s so layered and dense. That’s the sort of thing that I’m into. One day, I gave her this big canvas, and I watched her do this stroke that was so open-ended, this large arch. She just went for it. It wasn’t measured; it was about movement. I remember looking at it and thinking, “Oh, that’s her free moment.” That’s a good way to paint: [when] it’s in your body, and it’s intuitive. In the beginning, I was more illustrative, but seeing her work like that, I thought, these [strokes] can be building blocks. Little vessels of movement.

Sometimes the layers become my secret incantations on the surface with the paint.

What does the idea of layering mean to you?

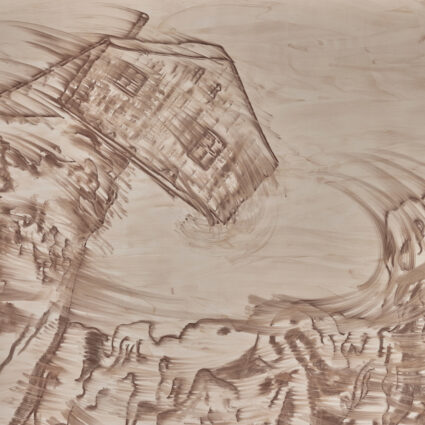

I read a quote recently—I can’t remember who said it, but they said something like “Painting is the only image with texture,” and that was really resonant for me. I’m not interested in flatness. I like the idea of creating these really tense, dense moments and then moments of clarity. I’m interested in thinking of my painting as past-present-future on the same canvas, pushed together. I almost don’t want people to know where it starts and where it ends. That is how it is for me when I paint. I’ll sometimes work on a painting for up to a year. Sometimes I’ll think something is done, and I’ll pull it out and see something else. I often paint over my work. I’ve talked about it in the context of being an Indigenous artist and making work that isn’t necessarily Indigenous-looking by a Western, colonized way of thinking. With language, too: I like to hide language in a lot of my paintings. Sometimes the layers become my secret incantations on the surface with the paint.

Thinking about expansiveness, working on a big scale, and how that doesn’t just speak to the physical thing, but to your experiences and identity, I wonder: do you ever feel challenged by the fact that the canvas is only so big?

No. For me, just in general, I really try to think about how to be more limitless in the way I’m expressing myself. I think of everything as being open-ended. Every painting I make, I can take it out and show it again in a different context. I’ve used paintings as performances, as a drop piece on the ground. I’m always thinking of ways to recycle my things, because they feel infinite to me.

Are there limits? What are they?

Being didactic. That’s the thing. As an Indigenous person, pretty much my whole life I’ve been told to be didactic and been told to explain who I am in this way, and I’ve been told that I need to be a specific kind of person. On the other hand, there’re ideas of community and ideas of who I should be. In the art world, especially as a person of color, people really want you to be didactic. So, working in abstraction has been something that’s been freeing for me in that way.

Returning to the idea of words—what is your relationship to the written word? Where are the words in your work from?

I take them from books; I take them from journals; I take them from conversations. This painting behind me says, “Daisies in the Sun.” It was in a letter from my dad; it’s a Captain Beefheart lyric. I come from punk parents, which is part of the reason I’m doing all this stuff around punk right now. I was looking at that letter, and I took his handwriting and projected it on the surface, then obscured everything but “Daisies in the Sun,” so I think of ways to have these sentiments that are private. I’ve been working with my grandmother a lot—I’ve been interviewing her—and I take quotes from what she says and put them into different projects. I’m really interested in conversation and storytelling in this way that is completely abstracted. In these textile pieces, I just talk to her about sports. I’m an Indigenous woman, and I’m into sports and punk and all these things: it’s me and what I’m into.

It’s nice to be reminded that we are all allowed to be complex, even in our public identity. I’m interested in how that relates to all the collaboration you’ve done—whether with family, other artists, or part of the collective you co-founded, Black Salt Collective.

As artists, we’re always told to be in our studio and have this serious artist time, but to me, I think I’ve always been community-oriented. I can’t grow without community; I can’t grow without conversation. Sometimes it’s just sitting with someone and working on something together. I always want to know what we can teach each other.

It’s so true that the evolution of most people’s work is born out of conversation, dialogue, looking at the work of others.

I didn’t go to art school; I don’t have an MFA. I’m pretty much self-taught. I think you go to grad school for the studio and the mentorship, and to have the time—these specific resources. But I’ve been doing this for so long on my own. I’m sure I could benefit from graduate school, but we’re in an interesting place where artists don’t need graduate degrees. We don’t need to go into debt to be expressive. I think curators are becoming really smart about the work that people are doing, specifically Indigenous people. That system for me isn’t something I really want to jump into. I’ve found my utmost support in community and friendship.

How have you found that specifically in Albuquerque?

I like Albuquerque, energetically. It feels like there’s a grassroots, DIY energy, and that’s something that I’m really inspired by. It’s about working with what you have. Here there’s such an interesting fabric. Indigenous culture is in everything, but it’s also commodified and exoticized, even though it’s indigenous. It’s this really intense and loaded but beautiful place. Coming back to it, I just feel like I’m supposed to be here. My family is here. My family has been here for many decades. And I also have space for the first time, and it’s changing the way I think about my work.

What interests you lately in your work?

I feel like in my work I’m always doing cultural and familial mining and excavating these things around the core of who I am, and how they come from all these different resources. I’m always thinking of ways to work these cultural faucets, because they are part of what I am.

What about other people—do you ever have any hopes of what someone might take away or what kind of experience they might have with your work?

I think the short answer is that I make my work for other Indigenous people to know that we can be expansive. That’s what I think it is.

Do you find that there are more channels and more venues that have an eye toward this broader curation of Indigenous artists now?

Overall, outside of here, outside of New Mexico, there is this monolithic idea of Native people, and the reality is that we are very vast; we’re very different. Our histories are intertwined, but they are also individualistic. I think that is something that curators are catching on to, and there’ve been some really interesting shows. On the rez, there’re kids out there, they’re just trying to work with what they have. Kids will make a basketball hoop; people will have a noise show at their chapter house. There’re these things that are happening, and they happen by any means necessary. To me, that’s what is really keeping the work moving.

Outside of New Mexico, there is this monolithic idea of Native people, and the reality is that we are very vast; we’re very different.

People just need space—and the power and opportunity that exists by having it.

Space is important, and after being in the Bay—there’s a scarcity narrative in creative worlds. How can we not fall into that scarcity narrative? How can we work with what we have and support each other? I even think of my work that way: what does it mean to create these dense worlds and spaces that are for me as an Indigenous woman. I’m really interested in space. Space—what a radical concept, right? As Native people, as urban people, there’s so much to this elusive thing. I’m interested in that. How can we create more space?

How do we?

I think people with money here should invest in young, emerging artists. And people outside of institutions. I’ve thought about that since returning here. There’s lots to be changed. I’ve seen shows with all white artists, and I’m like, “How?” I’m frustrated, because I’m from here and it’s 2019. There’s so much interesting work—specifically about this place by people from this place, who are working from a place of complete honesty. And are doing it on their own. I’m really emphasizing DIY culture, but that’s what’s inspiring to me, that’s where I come from, and that’s where most of my friends reside. I think younger people, still emerging artists, we’re looking at ways to work outside of these infrastructures. But at the same time, people with the money and the resources should realize that we need support. We’re in a place that feels like it is changing, and my hope is that we can change it for the better.

Photo courtesy the artist.