Mayeur Projects, Las Vegas

May 11 – July 11, 2018

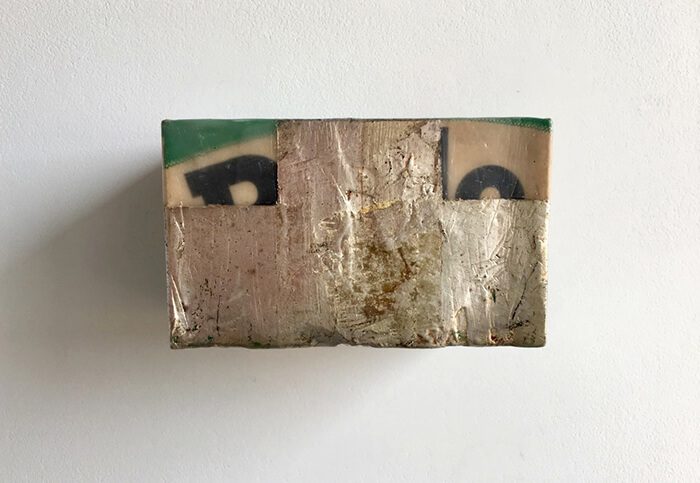

Stuart Arends is fond of saying that he lives in the middle of nowhere. Ever hear of Willard, New Mexico? The landscape around the artist’s house is austere, almost barren, with a view of some mountains off in the distance. He is “off the grid and under the radar” as Christian Mayeur, the founder of Mayeur Projects, wrote in Arends’s catalogue for the exhibition Tin Man, Slabs, and My Father’s House. It’s as if Arends, in his choice of a site for living and working, deliberately wished to evoke the idea of stepping into a void in order to make the work—but a void that is in actuality a transactional space where objects take on subtleties of meaning, even if meaning is bracketed only by the specificity of materials. In Arends’s way of thinking, an old Brillo box is just a Brillo box, albeit raised to the level of art object. In the piece Brillo, from 2017, just a few alterations—a coating of clear wax, some silver leaf, and the vagaries of the elements that have slowly begun to tarnish the silver—have rendered the work into something rich and strange. And perhaps Brillo is in its way a sly commentary on Andy Warhol’s famous appropriation of a commercial product, but there is no way to tell. One could only speculate that Arends might be subversively “tarnishing” the reputation of Pop Art. Then again, this sculpture might only be the product of a random act of found-materialism.

The minimal and the maximal can easily slip on fragments of each other’s disguises.

The truth is, what is revealed about any sculpture by Arends rests squarely in what the viewer brings to the work when encountering it. Arends’s sculptures don’t emote. If you care to interpret, you are on your own. And your clues are few: pigment, a slab of aluminum that hangs on the wall, a slant of ambient light, for example, in the series Slabs. Arends has stated that he works with things “that are not open to interpretation,” and yet, when looking at one of the Slabs and then concentrating on a section where the brushed aluminum has not been painted, you can make out a ghostly image of your own head—a spectral reflection that may be purely accidental in the scope of the artist’s intentions; this participation in, and momentary modification of the work makes for a subjective fugitive gesture. Did Arends realize that this would happen? How purely objective can any object be? The minimal and the maximal can easily slip on fragments of each other’s disguises.

The series My Father’s House is decidedly evocative and expressive. The forms hanging on the wall are literally made from material the artist took from the house he grew up in—an old wooden four-by-four that Arends’s father painted white, but only on one side. The artist had it cut into four-inch cubes that he subsequently altered with oil and wax, adding black-and-white geometric shapes, while also leaving patches of the original wood. The artist left the top and the bottom of each sculpture untouched so the grain of the wood becomes an aspect of the piece. Adding to that, the wood in general is partly distressed—cracked in places, and there are a few nail holes and stains. Consequently, on a sculpture so small, each defect reads as a deliberate choice having to do with an overall aesthetic, if not a meditation on pre-existing conditions, mortality, and one’s foundational roots.

An artist can categorically state that he is against interpretation, but every word, phrase, and accumulative act does not come out of a void. The void at the center of one’s creative energy is teeming with associations and passions, and the artistic process becomes a matter of the distillation of variables. In the middle of Arends’s “nowhere” are expansive horizons more complex and suggestive than he would have us believe. The viewer can participate in Arends’s work through a dynamic of personal discovery at the place where physical presence becomes its own excuse for meaning.