Artist talk and open studio: August 8, 2019, 5:30-7 pm

School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe

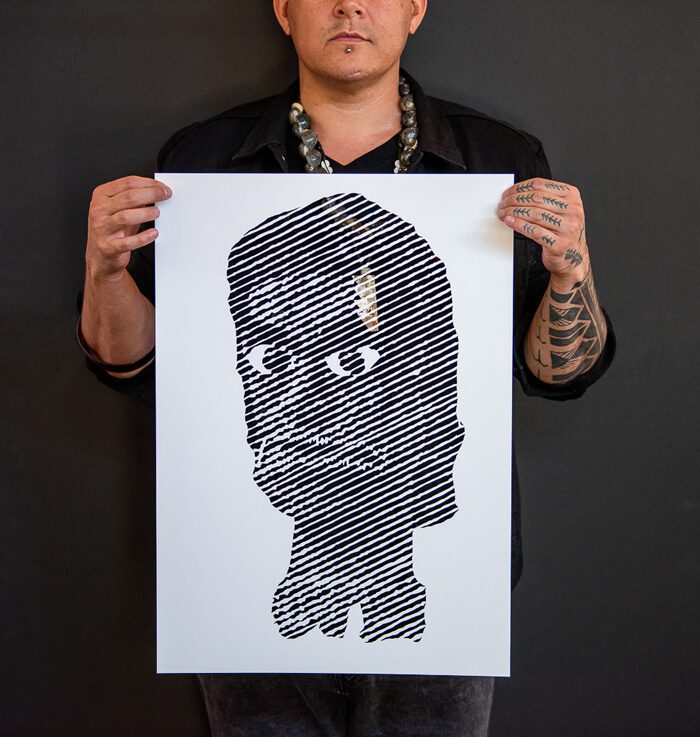

The work that Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) and Apache artist Ian Kuali’i makes today is largely born out of a longstanding connection to the landscapes he has lived and worked in, as well as a sense that these different places each hold unique lessons for their inhabitants. As the Ronald and Susan Dubin Native Artist Fellow at the School for Advanced Research, Kuali’i is putting his talent to work to create intricate works of hand-cut paper, as well as an expansive earthwork on a slice of the center’s undeveloped acreage.

Kuali’i has lived in Santa Fe for the last year, coming to call the city home after moving here upon receiving the first National Endowment for the Arts grant at the Institute of American Indian Arts. Along with opportunities to further develop his craft, Kuali’i has discovered that “there was a reason why” he wound up there. His time in Santa Fe has allowed him to continue to expand his visual language in paper, land arts, etchings, as well as in organizing, collaborating with fellow artist Ginger Dunnill on Ancestral Ink, a symposium on traditional Indigenous tattooing to be held on Sunday, August 18 at the Santa Fe Art Institute, for example.

We caught up with Kuali’i ahead of his artist talk at the School for Advanced Research on Thursday, August 8, 5:30-7 pm.

Have the landscapes in the Southwest had an effect on your work?

Most definitely. I’m simplifying a lot of things now. Many individuals that end up in the Southwest have experiences like this. There’s true light here; you see colors totally differently. There’s something ancient that blows through the wind… Those things start forcing your hand. This place is patient. It wants to show you things. There is this vastness, this open space and solitude. There are different lessons that this landscape can teach you.

What are you working on lately?

With the earthworks, it’s the idea of prayer, the land as audience, and asking the land for forgiveness—as well as forgiving ourselves. We don’t control the environment; we are part of it. With the piece I am working on for SAR, I’ll do something based on what the environment wants and what it offers me. I don’t go out with objects to leave behind. I typically find debris from the environment itself to create these pieces. At the same time, I clean the environment. For me, it is my responsibility to clean up trash and human waste left behind. That’s part of the practice.

When people think about creative process, they think about the artist looking inward. This is different.

It’s totally different. This is me being out on the land, in her space, and trying to pick up on what she’s saying. One of the things I do in the studio is I try to find some freeing and loose way of going about things. That’s what I do when I step outside, too. It’s more freeing than sitting in front of a massive sheet of paper and doing the tedious work of cutting to render images. To me, as much as I love my hand-cut paper, that whole process, it feeds a different portion of my brain and spirit. I find that stepping outside into the environment—or being loose in the studio with a brushstroke—those are the realest and most magical moments of creating.

How have your life and creative practice led you to earthwork and hand-cut paper in particular?

The hand-cut paper came about because of my urban contemporary arts practice and being involved in the graffiti movement and street art at a certain part of my life, even though I never identified as a street artist. It grew out of that and stenciling. I appreciated the cutting of the paper more than spraying the stencil. I saw the beauty in it and how delicate it was. And how precious in that delicate nature. I wanted to figure out a way to develop my own visual language that spoke to my Native Hawaiian culture—and how personal that is, too, as a modern Hawaiian. As for the land art—because of where I was [personally], there was a lot of healing and asking for forgiveness. There’s only one great forgiver. The only way to truly ask for forgiveness is that you have to start forgiving yourself first, and then you have to ask the land—especially the land that you are walking on at that moment—for forgiveness. I asked to be healed and I asked for forgiveness, and that’s how I came to that practice.

These practices are really tied to biography, then?

As a young kid, I had an amazing tree in my front yard. I would climb to the top when things were hard. I remember once climbing up the tree, I sat there and asked the wind to take my pain away, and the wind would blow. It felt incredible. As a teenager, I was outside less because I was trying to be cool, but I would walk and hitchhike everywhere on Maui. I was the weird kid with my backpack and headphones and a bamboo shinai, a bamboo sword. This stuff has always been part of me.

Was this the landscape you needed right now?

Absolutely. Life has changed, and this place has changed me quite a bit.