Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing—A People’s Perspective at the Branigan Cultural Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico, showcases the work of seventeen artists to shed light on nuclear injustice.

Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing—A People’s Perspective

July 15–September 23, 2023

Branigan Cultural Center, Las Cruces

Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing—A People’s Perspective is one big, swollen cry of the heart. The juried exhibition opened at the Branigan Cultural Center in Las Cruces, NM, a week before Oppenheimer came out in the theater. While the film focuses on the nuclear physicist himself, the exhibition draws attention to the communities Oppenheimer hurt. Namely, the exhibition—coinciding with Cara Despain: Specter New Mexico, another Las Cruces exhibition on nuclear injustice—speaks of Hispanic and Native communities in New Mexico whose land sits in the vicinity of the site of the first atomic test in the world or near uranium mines.

During World War II, Oppenheimer indicated to those in power that New Mexico, where the nuclear physicist had spent part of his youth, would be the ideal place for building the world’s first atomic bomb. Near the end of the war, he was also the one to point to the Jornada del Muerto, the small desert near White Sands, as the perfect place for detonating “Gadget,” the world’s first weapon of mass destruction. The area is now known as the Trinity Site, after the code name Oppenheimer gave the operation.

On July 16, 1945, the radioactive plutonium fallout from the morning detonation of Gadget fell downwind from the Trinity Site, on land otherwise worked and occupied by predominantly Hispanic and Native communities. Today, the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium still fights to have the U.S. government recognize and apologize to those whose health and lives were affected by the radioactive fallout, and also by uranium mining in the Southwest.

Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing was a joint effort between the Branigan Cultural Center and the TBDC, in particular Mary Martinez White, whose mother and many other family members died as a result of the radioactive fallout contaminating their water and land. Martinez White and the Branigan Cultural Center challenged artists from across the Southwest and the country to reflect in their art what nuclear testing on U.S. soil means to them.

Juried by Marisa Sage and Jasmine Herrera of the NMSU Museum of Art, the multi-media exhibition devastates the viewer, as it moves them from the figurative and representational of nuclear harm on human beings, to the symbolic and prophetic.

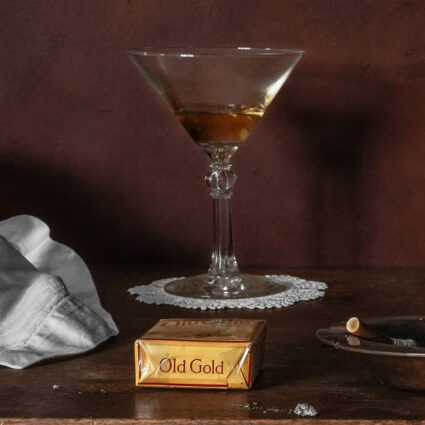

Take the exhibition’s promotional image, Come all ye Faithful (2018) by Las Cruces photographer Emmitt Booher. Here, people, seemingly dressed in white as though in a cult (a result of an infrared technique Booher used to take this photograph), are in the process of walking toward an obelisk—that represents where the tower that held Gadget stood before the detonation—as though pulled in by gravity or faith, or both.

The photograph illustrates the psycho-social phenomenon of mass numbing—or rather, what psychologist Robert Jay Lifton coined psychic numbing of the masses, meaning a decrease in horror for acts of atrocities and empathy for the victims of those acts. Like empathy for the communities who were downwind of the first atomic test.

Mass numbing to nuclear armament is said to be, in part, linked to atomic tourism. And that’s exact what Booher encountered right before taking this shot, while at an “open day” at the Trinity Site at White Sands Missile Range.

“It was really surreal,” Booher says of the tourists around him, and the atmosphere at the Trinity Site. “It was just carnival like.” People, he said, were “like moths to a flame.” As though they were “at a rock concert or something” and not at the site of the birth of weapons of mass destructions. They looked around for Trinitite, the green glassy residue left on the desert floor after the nuclear test (which the military prevents visitors from picking up). They bought souvenirs, key chains, stickers. They ate hot dogs. “The grill was at the [Trinity] obelisk, or something. It was just crazy.”

Artist Reto Sterchi took a more figurative approach to discussing the ravages of atomic testing on human beings—and one that doesn’t so much criticize mass numbing as it forces the audience to feel empathy.

The Swiss-born, California-based photographer first heard of nuclear testing on U.S. soil a few years back, when he still lived in New York. There, at a friend’s house, he came upon an essay collection, Acid West, by Joshua Wheeler. The fourth essay in the collection, “Children of the Gadget,” motivated Sterchi to partner with Wheeler for a project, a photographic journey throughout the Tularosa Basin, in search of human devastation and human hope.

Sterchi is shocked by the facts to this very day. “I didn’t even know they tested the bomb on U.S. soil,” he says of the U.S. government and military. “That they tested the bomb in New Mexico. And sacrificed their own people.” His portraits of Downwinders are, in so many words, empathy machines. “I felt like my job was to just get the people as real as possible,” he says. “To show them.”

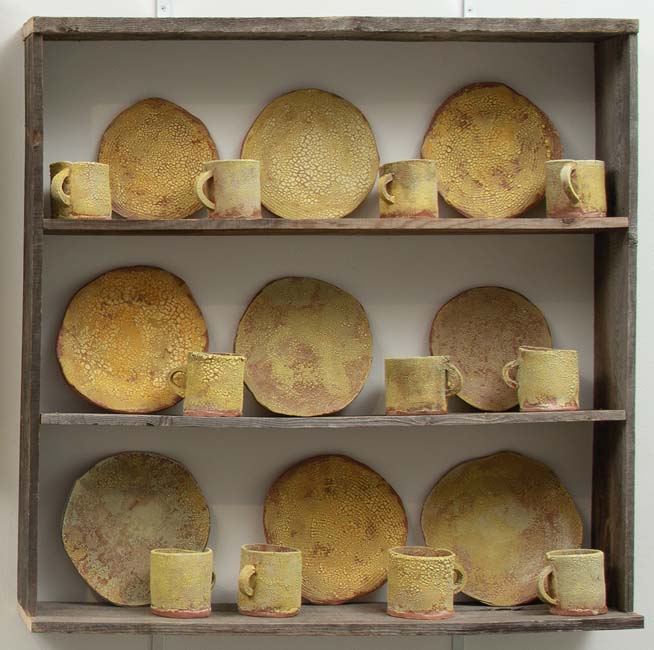

Serit Kotowski, artist, potter, and activist currently based in Taos, chose instead to represent the victims of nuclear testing in New Mexico in object and in name. One of the raku clay works Kotowski brought to Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing is titled The Other Trinity Test Tower of 500 Souls (2020). From the side, the tall object reminds the viewer of a gray twister; inside it, though, it is a dust storm of names scribbled as though on the walls of a prison. These are the names of 500 of the many New Mexicans who died of complications from radioactive exposure caused by the plutonium fallout.

What Kotowski wants you, the viewer, to do now, is simple: say their names.