An artist and an architect map a once-and-future freedom colony of New Mexico.

Taos artist Nikesha Breeze met her father for the first time when she was ten years old. He was homeless on the streets of Portland, while she was growing up beyond the city’s southern outskirts in the small town of Sherwood. “I was the only black girl in my entire school, kindergarten through high school,” says Breeze. “It was a very white, very redneck town where it was dangerous to be.” She and her ten siblings were brought up by their mother, whose heritage is Assyrian, so Breeze’s transient father was her first direct link to black identity.

“He’s very dark black, very tall, a beautiful man,” Breeze says. “When I was little, I had all of these stories in my head of where he came from, where my blackness came from.” She’d see her father intermittently throughout her childhood and early adulthood. One of his tales held a strange clue to her family history. “He used to talk about his grandma and going to visit her out on the mesa,” Breeze says. “He’s from Oregon, and there are no mesas in Oregon.”

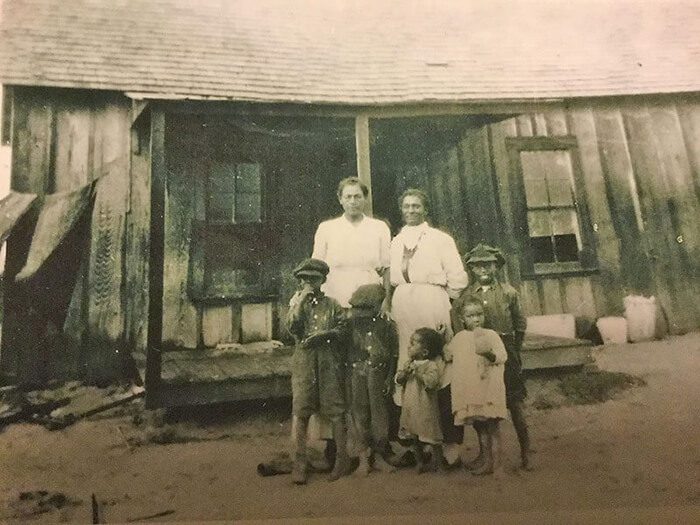

About a century earlier, Breeze’s great- grandmother, Jessie M. Blacknall, was far from the only black girl in her hometown. Born in 1916, she was a daughter of one of the founding families of Blackdom, New Mexico, a settlement about eighteen miles southeast of Roswell that was the state’s first all-black community. Clinton Ragsdale, Breeze’s great-great-great-grandfather, was an early patent holder of Blackdom. Breeze learned of her connection to Blackdom just three years ago, after nearly two decades of living in Taos. The revelation inspired her to pivot from a long career in the performing arts to a serious practice as a visual artist.

They walked more than 1,200 miles to Roswell, New Mexico, where Boyer laid claim to a tract of land outside of town.

At the center of Blackdom’s origin story, there’s another wandering patriarch. Francis Marion Boyer was from Georgia, and his father was a freedman who fought in the Mexican-American War of 1846. Boyer married a woman named Ella Louise McGruder and started a teaching career in Georgia, but soon his grassroots efforts to battle Jim Crow laws incited threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Unable to board a train because of his skin color, Boyer fled Georgia on foot with one of his students sometime around 1896. They walked more than 1,200 miles to Roswell, New Mexico, where Boyer laid claim to a tract of land outside of town. Ella and their children followed Francis in 1901, two years before Blackdom was officially incorporated, and they set about fulfilling their vision of an independent black society.

The story of this turn-of-the-century freedom colony has also deeply informed the life of Gregory Waits, a Santa Fe architect who’s working to create a monument to Blackdom. Blackdom became a ghost town in 1930, but through the efforts of these artists and others, it seems destined to rise again in the American imagination.

/

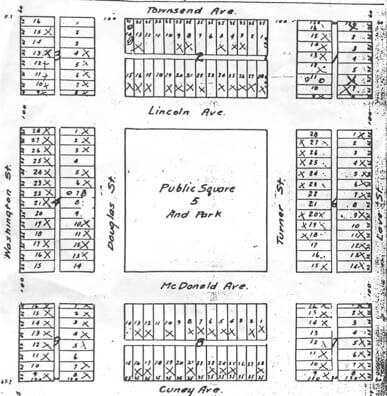

Gregory Waits sits before his laptop at a cafe in downtown Santa Fe, examining a schematic of Blackdom’s original town plat. It’s a familiar formation, with a public square in the center and gridded streets surrounding it. “They were on this property that was sort of devoid of racism because of its remoteness,” he says. “Of course, Blackdom itself is part of Jim Crow in many ways. They didn’t let them settle anywhere near Roswell.”

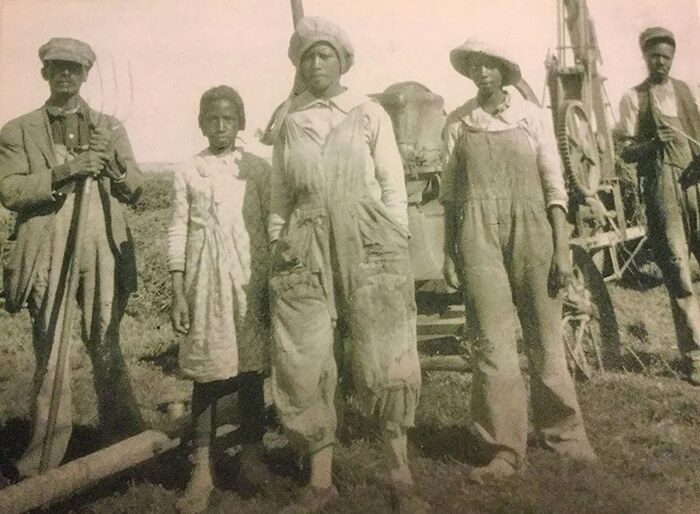

Despite its isolation, Blackdom thrived in the years after its founding. Boyer took out newspaper advertisements to attract black settlers, and about twenty-five families answered the call in the first seven years. At its height in the 1920s, the Blackdom townsite and its surrounding patents covered more than fourteen thousand acres of land. About three hundred people lived there, enough to support businesses such as a newspaper, a hotel, and a post office.

Waits learned about Blackdom in 1999, when he was an architecture student at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. He was searching for inspiration for his thesis project, and a friend brought up the idea of a monument to the historic freedom colony. “The internet was slow as heck, so I remember just digging around a lot in the library to find a map of Blackdom,” says Waits. Blackdom’s former site is now surrounded by private land, so he had to pull some strings in Roswell to visit it. All that remained were the weathered foundations of the schoolhouse, but as a former high-school chess champion, something about the classic grid of Blackdom’s plat sparked his imagination.

“This was the standard template whenever someone wanted to develop a township because it provided sort of a fortress,” Waits says, tracing his finger around the square. “This pattern represents all of the United States. I decided to look at the utopian impulse of Francis Boyer, and explore that utopian impulse throughout the history of African Americans.” Waits completed his thesis in 2001, and it’s equal parts architectural structure and walkable sculpture. “It’s about the tension of being able to access the public square,” says Waits. “African Americans had no seat at the table.” As he flips through more images of Blackdom’s town plat, a series of rigid lines appear all around the central plaza. With the geometry of the plat as his starting point, Waits drew inspiration from the deconstructivist structures of Peter Eisenman and the brutalism of his mentor Antoine Predock to tell a story that spans far beyond Blackdom itself. “You start to get this deconstructed plat that represents each of the migrations of African Americans,” he says.

Near the beginning of the progression is a tiered stage that references the spectacle of the auction block. Subsequent passages are abstract representations of the Underground Railroad, the Civil War, the Jim Crow era, the Civil Rights Movement, and other key chapters of African American history.

The monument is a giant labyrinth of pathways, ramps, walls, and blocks, forcing visitors along a single, zigzagging path that obscures and evades a central courtyard. Near the beginning of the progression is a tiered stage that references the spectacle of the auction block. Subsequent passages are abstract representations of the Underground Railroad, the Civil War, the Jim Crow era, the Civil Rights Movement, and other key chapters of African American history. The journey ends with an arrival in the public square, which features a waterfall with a screen behind it showing an ever-shifting mosaic of black faces.

“There’s this idea of approaching a sense of identity,” says Waits. “It’s not an easy path, but there’s a moment at the end where you see your face up on that wall and say, ‘Wow, I see myself now.’” Waits’s effort to bring the monument to fruition has been a difficult road in its own right.

/

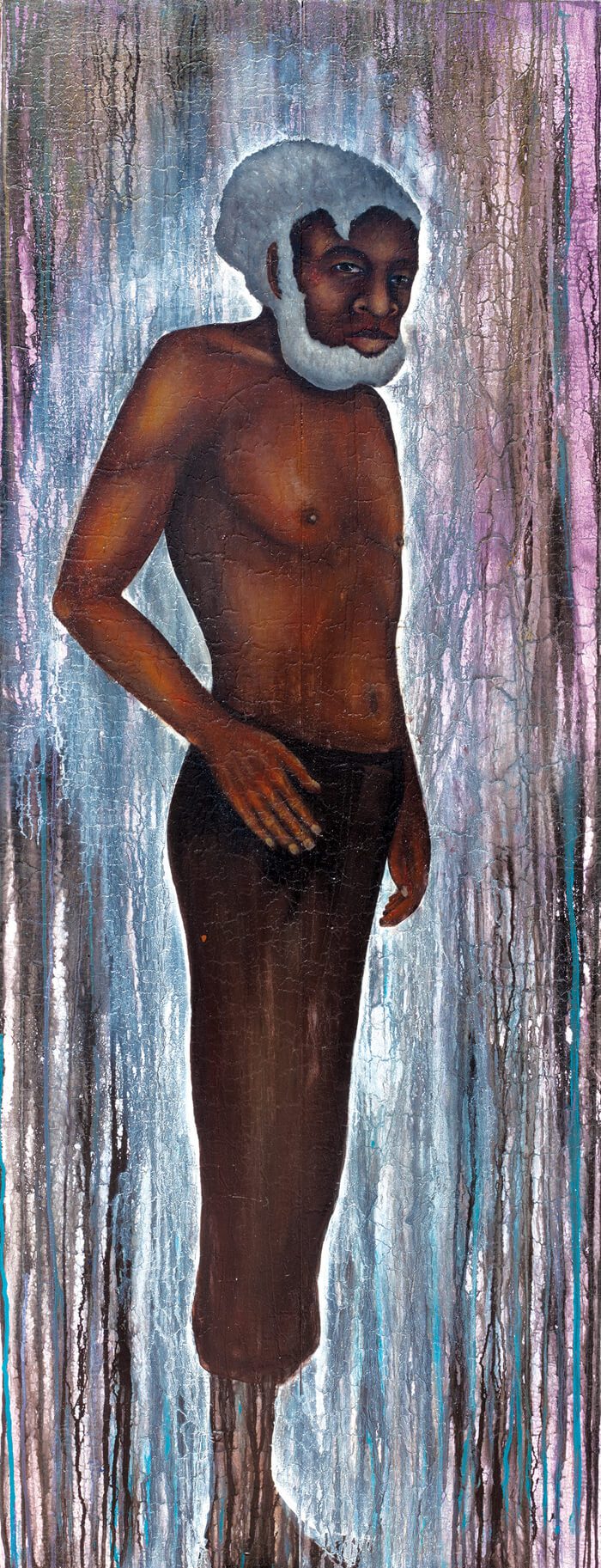

“When we’re cut off from our histories, we’re cut off at this real root of time and place,” says Breeze. “How do we move from that timeless, placeless space to something else?” It’s spring of 2018, and the artist is conducting a tour of her solo exhibition, Within This Skin, at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos. The paintings and wall sculptures in the Harwood’s Studio 238 project space are Breeze’s answers to that question. They also represent a milestone for the institution: this is the first solo show by a black artist in the Harwood’s history.

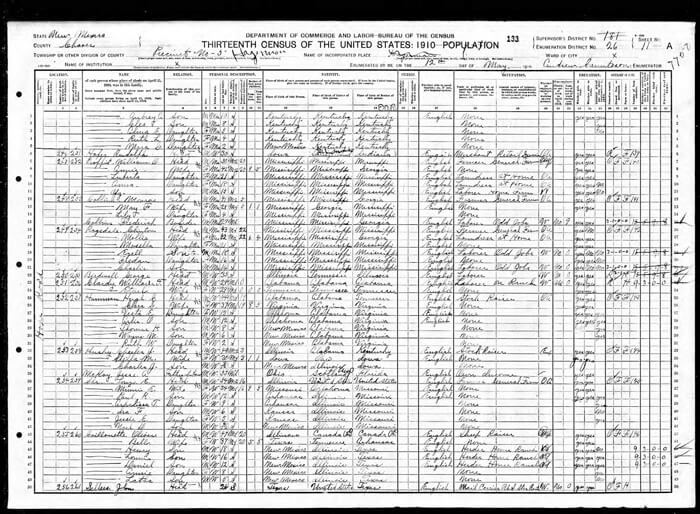

Two years earlier, in 2016, Breeze lost track of her father for an unusually long stretch of time. She was determined to fill the significant gaps in the stories he’d told her, so she signed up for Ancestry.com. The tale of Blackdom came together, piece by piece, through records of her family history.

“This fount of images began to pour through my body, because I finally had a root,” Breeze says. She brought home old closet doors from Habitat for Humanity and started rubbing dry pigments and ink across their bare surfaces. Vivid and highly specific compositions sprang from the abstractions. Her first painting showed a ghostly grandmother, who became clearer and darker with each layer of pigment, until her hands gained a bloodstained hue.

The residents of Blackdom must have felt a similar sense of wonder at the world they’d built. Among them lived W.T. Malone, the first black man to pass the New Mexico Bar exam. White residents of the surrounding towns joined them for a barbecue and baseball game on Juneteenth, a celebration of the abolition of slavery in Texas. Most notably, the town struck oil in 1919, marking the start of years of prosperity for the village. Blackdom was nothing like the places they’d left behind.

Breeze’s family research came to an end sooner than she expected. She’d moved from Ancestry.com to other databases with records from Southern slave plantations, but the paper trail petered out just a few generations past her Blackdom ancestors. “One of the grandmothers was identified only as ‘Dinah,’ which was a Jane Doe term for a black woman like ‘Sambo’ was for men,” says Breeze. “It makes you feel like something has been stolen from you, like really stolen. Dinah kind of dispersed me into this wider study of black culture.”

Her subject matter expanded as well: Within This Skin features imagery of children huddled together as though on a slave ship, a lynched man in a sunlit forest, and an encounter between a small black child and a group of towering Klansmen. A series of masks made from hand-dug southern New Mexico mud hangs on a narrow wall. Breeze modeled the sculptures after her own face but manipulated their features to create imagined depictions of her ancestors.

It’s a prayer for justice for indigenous black and brown people. How do we honor these lives?

“It was as if I was recreating all the people of Blackdom,” Breeze says. “It’s a prayer for justice for indigenous black and brown people. How do we honor these lives? There’s that total feeling of anger and absence and unjust reality that is carried through this trauma, and then on the other side, there’s a celebration of resilience.”

/

There’s already a Blackdom memorial, but it’s a humble placard on a roadside not far from the original townsite. In 2006, Waits heard about an effort to create a larger monument to Blackdom in Roswell, spearheaded by the Rev. Landjur Abukusumo of the Blackdom Memorial Foundation. Waits switched the title of his thesis from “Multiple Migrations” to “Blackdom Memorial Gardens” and handily won the request for proposals. A plot of land in downtown Roswell was earmarked for the project in 2007, and the New Mexico state legislature granted the project $250,000 two years later.

“Everyone was jumping on it, because it seemed like it was moving forward. I was getting phone calls and bids,” says Waits. “Then the budget got cut, so we reduced its scope. Things kept getting tighter, and Roswell put up all of this red tape, to the point where the project was just blockaded.” Waits saw the slow-burning effects of the 2008 Great Recession as the monument’s preemptive death knell. What had looked like a modern-day redemption arc uniting segregated communities became a disappointing echo of the past.

Blackdom itself suffered a strangely analogous fate. Lacking support from surrounding communities and facing prohibitive local legislation, its residents struggled to drill artesian wells and many had to haul their water. The wells that did exist weren’t deep enough to survive a series of droughts. Blackdom’s crops were plagued by worms, and by the late 1920s its residents faced foreclosure. The Boyers provided water and financial assistance to their neighbors but were forced to dissolve the community soon after the Great Depression started in 1930. Some of Blackdom’s residents scattered to nearby towns, while others helped the Boyers establish Vado, New Mexico. There, Blackdom lived on through the storytelling of Francis and Ella Boyer.

Waits hasn’t given up on Blackdom, either. He continues to work with Reverend Abukusumo on the monument project and has recently connected with Los Alamos historian Dr. Timothy E. Nelson, who helped uncover evidence of Blackdom’s oil boom. Waits has also tapped his connections in the architecture world, including David Adjaye, one of the architects behind the National Museum of African American History in Washington, D.C. “When he heard ‘Blackdom,’ he said, ‘That sounds famous already,’” Waits says. He’s now searching for funding and potential sites for the project in Chicago or New York, although there’s also still a possibility of founding an artist residency on 640 acres of former Blackdom land owned by a descendant of the settlers. “There’s no reason the monument has to exist in Roswell, or even New Mexico,” he says. “I think that there’s a consciousness out there, and Blackdom is a part of that. Francis Boyer is out there spooking us all.”