Patrick Kikut reflects on meeting and engaging with Juárez portrait painter, Juan Manuel Rena Niño in the early 2000s. Kikut exhibited his portraits at No Man’s Land Gallery in 2004.

This article is part of our Living Histories series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 9.

On January 1, 2000, I was happy to wake up and see that the world was not in imminent danger due to the conspiracy theory that computer glitches would catch us overextended into the digital world. Remember, planes would crash, power grids would shut down our basic utilities, and we would descend into violent chaos. People were stocked with water bottles and plenty of ammo. A spaceship was drafting behind Hale Bopp Comet. Remember that freakout?

Anyway, I loaded up my truck with some clothes, art supplies and drove down I-25 to be the first artist in residence at the Border Art Residency. I was awarded a six-month residency at BAR where I planned to explore the border lands while living and working in a beautiful, refurbished cotton gin in La Union, New Mexico. I was motivated to engage in the land and culture and paint. Also, I was looking forward to meeting the artists and players in the El Paso/Juárez art scene. That’s where I found Juárez painter, Juan Manuel Rena Niño.

I loved to visit Juárez. Walking over the bridge was a thrill. The sounds, smells, and energy were enticing. It was electric, human, and overwhelming in scale. Unruly sprawl and the transient nature of the city makes it challenging to pin down the exact population, but I remember hearing that about 1 million people resided there. Visiting the famous Kentucky Club and (what I knew) as the Mariachi Market were always on the list of things to do. Eventually I connected with Rena Niño and made a visit to his studio part of the tour.

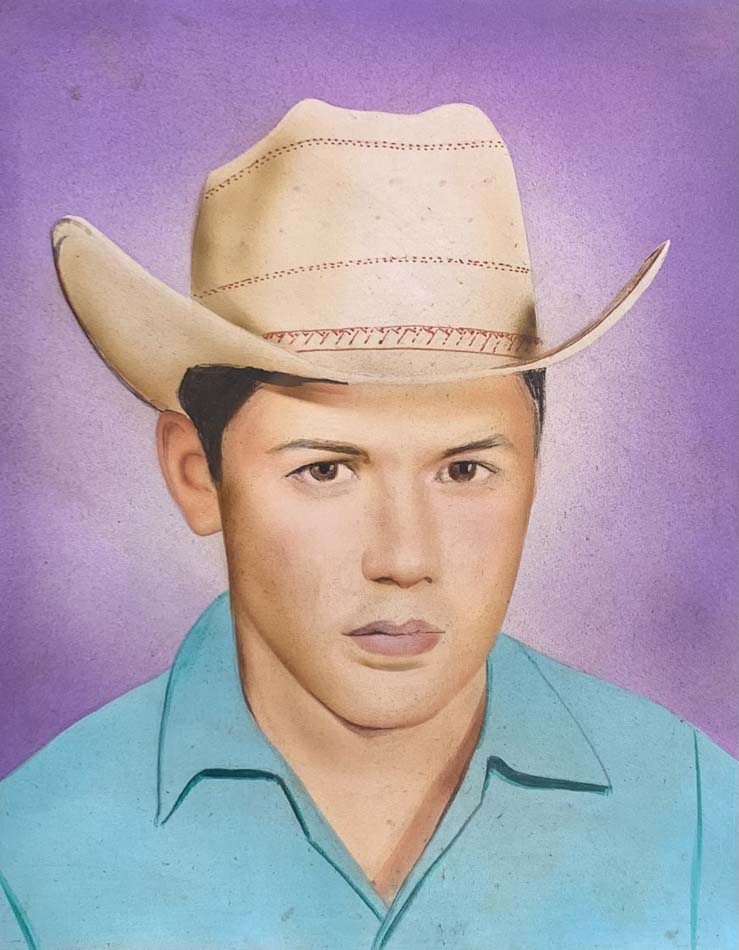

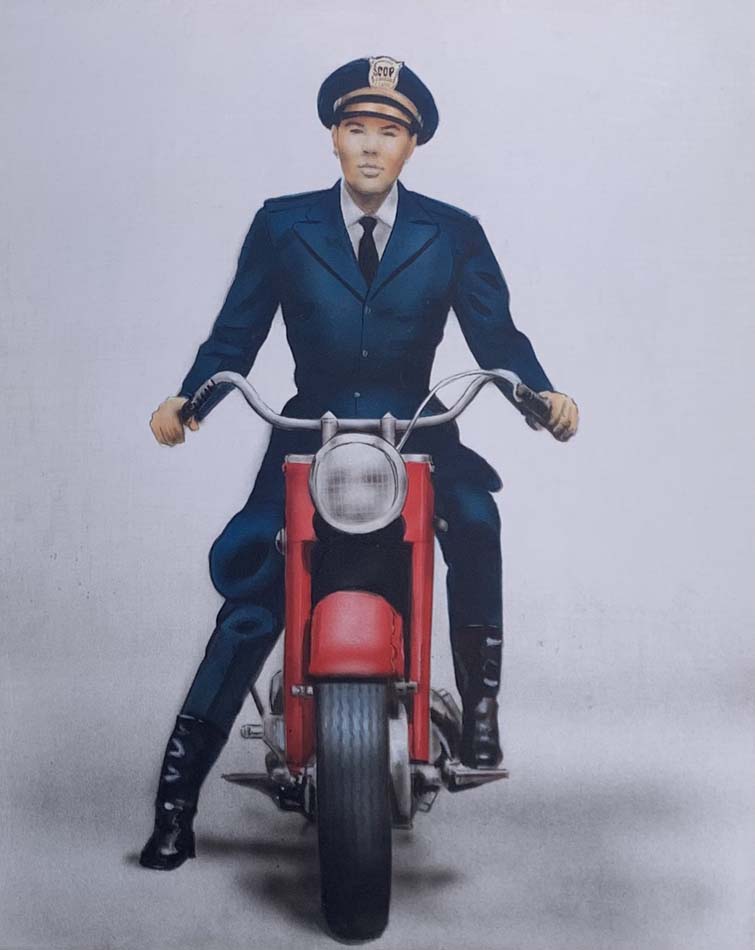

I first noticed Rena Niño’s studio on the bustling Avenida Benito Juárez and was impressed with the portraits that hung in the window of his shop. One painting hung next to a tattered black and white photo of about twelve well-dressed men posing at an outdoor ceremony. The painting was a full color copy of the photo but depicted the men in pinstriped Armani suits. All with perfect fits! I entered the studio, introduced myself and was immediately taken by a small painting of a handsome young cowboy. I bought the special painting and was thrilled that I had traded money for art. This was new to me. Soon I was back and bought another image of a motorcycle cop. I was impressed with Rena Niño’s capacity to create paintings that were detailed yet somehow economic. I had Rena Niño fever.

Three years later I was back in Santa Fe, living on lower Agua Fria and running No Man’s Land Gallery which was a small space I created out of an old shed in my backyard. I wanted to have a Juan Manuel Rena Niño exhibition and did my best to contact him from Santa Fe. My Spanish was as limited as his English, and this was before everyone was connected by computer and cell phones. If I wanted to exhibit his work I would have to drive to El Paso, cross the border and find him in his studio. So I did that. Driving south and then walking over the Rio I was optimistic, thinking that this would be a straightforward proposal. If he was interested, we would select paintings and split the sales fifty-fifty. I pushed through the turnstiles and started my walk down Avenida Juárez not knowing that I had lot to learn.

It was midday when I entered his dark studio. My eyes adjusted from the bleached sunlight outside and I made out Rena Niño who was in the back of the shop cleaning brushes. He was in his late fifties, about five foot, seven inches, thin and tranquilo. There was a young boy who was helpful in translating. Surprisingly, he rejected my proposal. If I wanted to show his work, I would have to buy it from him. I understood his perspective. He did not want to see his work disappear over the border, hoping to sell it and trusting that I would return with the money. I tried to ease his mind and offered to bring him up for the show; maybe he could use my studio and get some commissions or something. Still, no dice.

On the drive north with an empty truck I was discouraged and now felt silly for asking. What seemed like a wonderful sure thing now felt like a distant fantasy. What was I thinking? Who does that? I could have been working in my studio.

But I really wanted to show his work. Then, it occurred to me that the only way to show his work would be to buy the work outright. This was a gamble I was willing to take. With that understanding, my plan was to drain my meager savings account and return the next weekend with cash.

So, I pointed my truck back down I-25 to Juárez. On the drive, I thought how fantastic it would be if a dealer (or collector) came to my painting studio with cash. Anyway, I put that aside thinking that even if the show was a flop, I loved the paintings and would be happy to quadruple my Rena Niño collection. Later that day, in his studio, he presented me with work that was available, and I made my selections. I paid up and asked him to sign the work. He refused and explained he did not consider himself an artist because he painted commissions for patrons who told him what they wanted. The paintings he sold me were commissions, but he had never received final payment for them. In the end, I crossed the border with twelve paintings packed into large Mexican shopping bags.

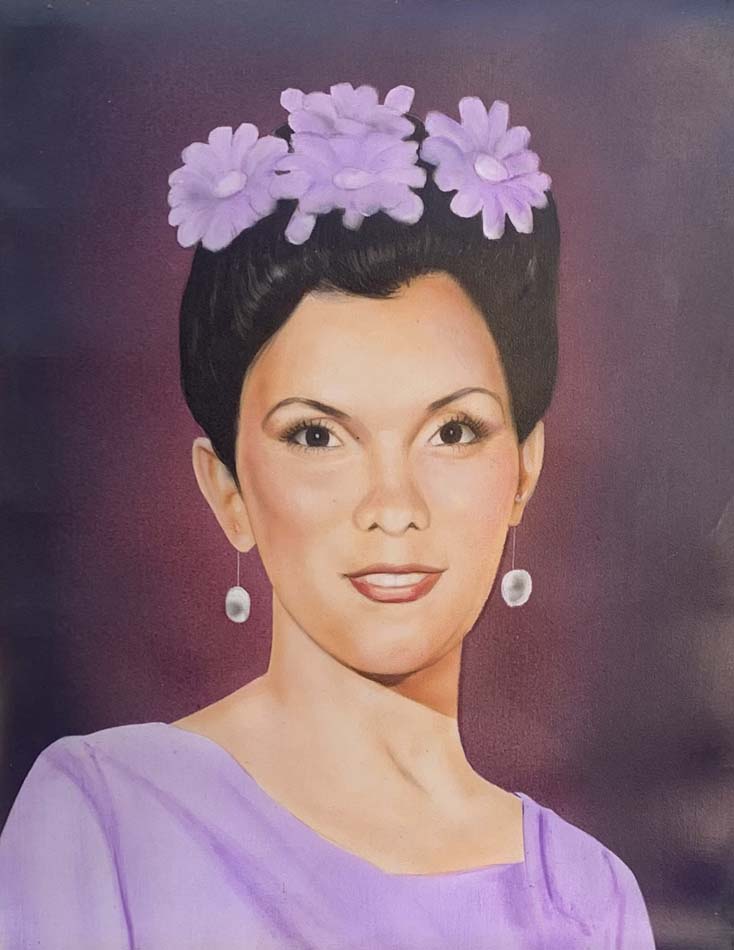

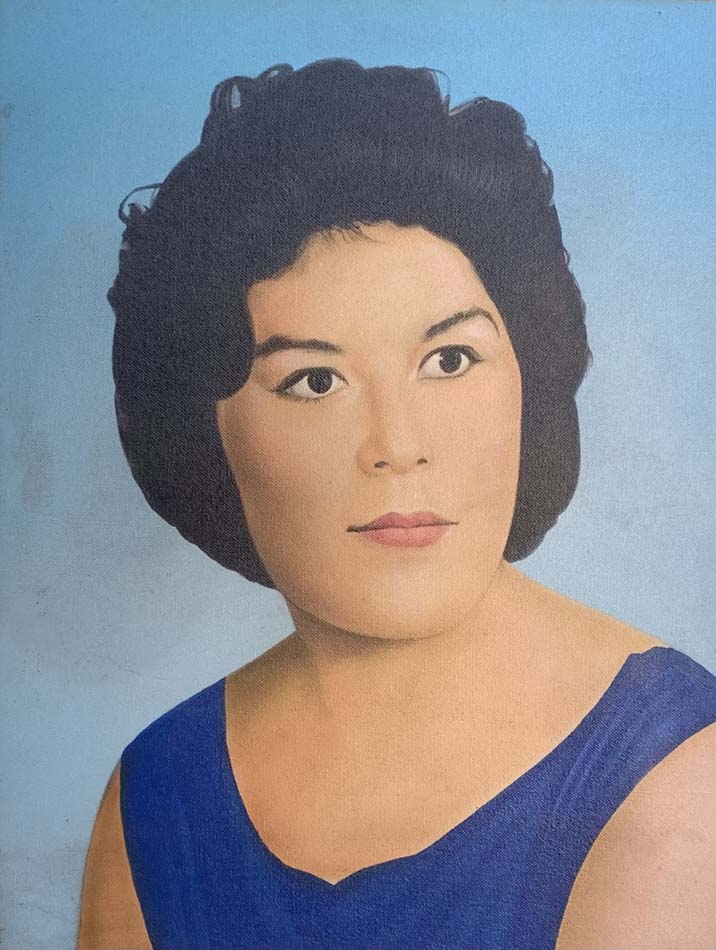

I got a room at Hotel El Paso and unpacked the paintings and spread them out on the bed. It was like a movie scene, but instead of cash on the bed it was Rena Niño portraits! On the bed was a single image of a military man, a stylish boy with a pompadour, a loving young couple, a young lady with violet flowers in her hair, a horse and rider, a stern looking policeman, all with flat colorful backgrounds that kept the focus on the subjects. I fussed over the paintings for hours then finally put them aside so I could get some sleep.

The next day on the drive up north, I realized the paintings were often commissioned by someone who was grieving the loss of the person depicted, yet the work had ultimately been abandoned. To add to the mystery, there were no titles or dates. I got the feeling that he had been working in that studio for decades so guessing at when these paintings were created was impossible. Looking at his paintings, I wonder about the subjects as much as the patrons. They are haunted, and timeless.

I was eager to install and light the work at No Man’s Land and share the work with the community. The show was handsome, and the conversations were lively. My art gamble paid off. Twenty-something years later, I am still pleased knowing that Rena Niño’s work is holding a place on a few walls around the region and still happy to share my personal collection with interested visitors to my home.

.

With this story in mind, I returned to Juárez on November 11, 2023, to see if Rena Niño was still working in his shop on Avenida Juárez. His studio was not where it was in the early 2000s. A lot has changed in Juárez and El Paso. Rena Niño’s studio is now a dental care office that specializes in extractions. I could not locate Rena Niño. Without any evidence, I imagine that he returned to Mexico City (where he was trained) to continue his work.