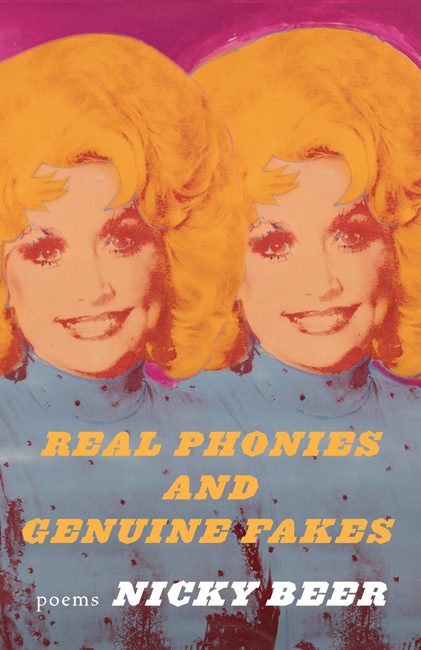

Denver-based poet Nicky Beer’s third collection, Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes, is a clever, probing look into the collective desires and fears underlying our love of illusion.

Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes by Nicky Beer

Milkweed Editions, 2022, paperback and ebook, 104 pages.

Advance praise: A Lambda Most Anticipated LGBTQIA+ Book of March 2022.

For fans of: Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs by Chuck Klosterman and Magical Negro: Poems by Morgan Parker.

The penultimate season of Amazon Prime’s Emmy award-winning television series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel—a show focused on the misadventures of Midge Maisel, the eponymous midcentury housewife-turned-comedienne—is not the madcap, zinger-filled escape that its viewers are used to. Perhaps in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which delayed the season’s release for two years, the line between humor and heartbreak, and life and art more broadly, is increasingly blurred, emphasizing how difficult it is to maintain the illusion, to keep up the act, as the screws tighten. By the last episode, Midge must pull herself away from the hospital where her ex-father-in-law’s life hangs in the balance to perform a pre-scheduled gig, and though she makes hilarious riffs on very real matters of life and death and God, she doesn’t attempt to conceal her fear and uncertainty.

Award-winning Denver-based poet Nicky Beer makes no claims to being a comedian, but throughout her third and latest collection Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes, released earlier this month by Milkweed Editions, I’m reminded of Midge’s last set—the performer who slips in and out of the act, an act of mastery and of supreme vulnerability.

The title is already something of a giveaway—the very idea of “real phonies and genuine fakes” calls to mind a circus booth manager telling us to step right up! Beer takes direct inspiration from this and other traditions of illusion, an expansive umbrella under which she fits poems on drag and disguises (“Drag Day at Dollywood,” “The Demolitionists”), forgery and false sympathy (“The Benevolent Sisterhood of Inconspicuous Fabricators,” “Kindness/Kindling”), magicians and movie stars (“The Great Something” and a number of poems starring Marlene Dietrich), and taxidermy and stage tricks (“Two-Headed Taxidermied Calf,” “Cathy Dies”). An entire section is dedicated to “The Stereoscopic Man,” an invention of Beer’s based on the stereoscope, that ever-popular binocular optical illusion-maker, and René Magritte’s 1927 painting Portrait of Paul Nougé featuring a man opening an abstracted door on the other side of which is himself, doing the same thing just out of frame. The cheeky poem titles and subjects she chooses to inspect within clue you in to the fact that this is performance, with Beer controlling the show. The only question is whether the standup set will be performed for maximum laughs or played straight. Beer does both. Veering between full-on jokester, esoteric performance artist, and masterful dramatic actor delivering a gut-wrenching monologue, she lands somewhere in the middle, a generous magician who lets us see the mechanics of the tricks and of herself.

A prime example of this is her cycle of poems featuring her invented “stereoscopic man.” The figure is a vehicle for play with form, with each poem split into columns as though viewing them through a stereoscope, and on words, on display very clearly in “The Stereoscopic Man’s Last Will and Testament”:

To my heirs I leave

my right to what

is left of me

But Beer is here to probe and provoke, not simply perform, leading to lines that directly address the trickery of the illusion, as in “The Stereoscopic Man and Binocular Vision”:

What’s there when you peer

through the lenses is a three-dimensional

fraud a con that thrives

on your eyes’ bumpkin trust

Real Phonies is a book of poetry about intentional and unintentional misdirection written and released in the Trump era, a time full of blatant and dangerous lies, targeted disinformation campaigns, propaganda, and conspiracy theories. It’s hard not to surmise that Beer’s collection is, at least in part, a response to this climate, however oblique. But Beer’s choice to focus on “fakes” in general, with particular emphasis on fakes that are antiquated, rather on the events that have transpired since the 2016 presidential race, is not an avoidance of contemporary politics, but an entry point. A bi/queer woman poet, Beer’s identities inform poems such as “Drag Day at Dollywood,” “Self-Portrait as Duckie Dale,” and “Dear Bruce Wayne,” which address the thrills and anxieties surrounding non-normative performances of gender and queer desire, as well as her use of Marlene Dietrich—the iconic bisexual Golden Age film star—as a leitmotif. They also sharpen her examination of the Western cultural fetish of the dead/artificial/otherwise powerless woman that underlies the male gaze throughout the collection, most notably in “Forged Medieval Church Fresco with Clandestine Marlene Dietrich”:

Tell me we don’t want all our goddesses

flattened and pinned to a wall, wings spread

and immobile.

“The Great Something” is one of many poems in the collection addressing our preference for diverting lies over illuminating truths, a tendency that has baffled the earnest political commentators of our day. “Steal their wallets, turn their wedding rings into eggs—they don’t mind. / But this was something else.”

However, Nicky Beer’s poetry is about the contemporary and the ancient, the political and the personal. Like Midge Maisel’s last set, many of the poems of Real Phonies confront death, life, and God with humor and an earnest vulnerability, from likening the sound of the word suicide to “the undulations of black and orange furred caterpillars, revolting and adorable” in her poem “Etymology,” to the credo-esque poem “The Poet Who Does Not Believe in Ghosts,” which explains this “unpoetic” mindset as stemming from the philosophy that “it is death, and not the rainbow / that is God’s covenant with mankind.” And like that last set, death permeates every page of the collection.

Unlike Midge, though, Beer’s exploration of and vulnerability about death doesn’t uncover fear, but acceptance, even curiosity, about this ultimate and final companion to life. The last poem, “Revision,” focuses on the dead pieces of ourselves we constantly slough off—hair, nails, scabs—and ponders if these are “maybe not the creepshow I think.” Death is known as the great equalizer—maybe it is also what turns both performers and poets alike into people. No more and no less.