As Raychael Stine guided us to her studio on the fringes of the University of New Mexico campus, where she has been an Assistant Professor of Painting and Drawing for the past five years, I realized that all my questions were actually the same question: Why dogs? The dogs in Stine’s paintings aren’t obvious at first, but they are almost always there, in a floppy ear, a sloppy grin, or a perfectly rendered pink nose. Our conversation wound circuitously through gardening, the history of painting, working with students, and learning to be an empathic human—and all of these topics eventually led back to the dogs.

Lest the reader be put off by all this dog talk, let me emphasize Stine’s paint-handling. At the risk of sounding melodramatic, Stine’s command of her medium evokes in me a similar response to my first teenage experiences seeing Velazquez’s or John Singer Sargent’s oil paintings up-close: an initial shock that recognizable subject matter can coincide with such loose and freewheeling brushstrokes, followed by a flutter in my chest: pure pleasure. But there’s also a joke in Stine’s paintings, which emerges in part from how dogs, painted in such a brightly colored and playful manner but with the utmost skill and care, can evoke such depth of feeling. And like that of any great comedian, the humor in Stine’s paintings is dead serious. She has thought about dogs more than perhaps any artist I’ve ever encountered—their significance in history and myth, their therapeutic value, the love of which they are capable, and which they make us capable of as well.

Chelsea: I was reading an interview you did with Arthur Peña, and you mentioned that you started painting dogs when you were seventeen?

Raychael: I painted dogs even before that. I was the kid who paints the dog from the first thing you draw. But I started very seriously painting my dog, Pickle, when I was seventeen. I think I was trained to see it as something dysfunctional, like obsession with your dog. But for me, it was a way to be in touch with my humanity, and with feeling, and love. I learned how to be an affective person through interacting with her. And I was on my own, starting at about seventeen. It was just me and Pickle. I actually painted her in some capacity from that time until her death. And a lot of the time I painted about her upcoming death. Even when she was a baby, I was like, “Oh, she’s going to die.”

I do that with my cat. He’s only two.

Yeah, like, “You’re going to die, oh God.”

I know, I know.

But the beautiful thing was, I was able to stop fretting about her, and projecting, and obsessing over her various pains. And right when I was able to do that, she actually did die. It was this wonderful, beautiful experience. The paintings at that point in time were very clearly about that dog, on one hand. And then on the other hand, they were about having this intimate human experience, even through the process of painting. Because painting is like petting, and it has a certain engagement. But it evolved into an understanding of an interconnected flow, or energy, and joyful exuberance in life. So then the dog starts to come out of the paint in that way.

My partner and I saw your paintings in Marfa last year at Eugene Binder Gallery. We walked into the space and just started laughing. I don’t know if you mean for your paintings to be funny.

No, they’re funny. They’re funny, and they’re silly in a way. And the thing that I adore about them is that the majority of people don’t see any dogs at first. I’ve had a lot of conversations with people that are really funny and telling, because there’s a whole group of individuals who have a certain idea about what serious painting is. And they’ve come up to me and said, “Oh, it’s so great to see paintings that are expressive, non-representational, pure, exuberant abstraction.” And I say, “Yeah, that’s a dog painting.” I’ve had people get angry and say, “Well, you just ruined it for me.”

I was also trained to believe that you should not see faces in an abstract painting—that smart painting, smart engagement of the painting, is not anthropomorphizing it. But the thing that I find so important, that I try to champion, is that the way that we learn to understand ourselves is to witness some mirroring of ourselves, or of some other aspect of the world, in something else. And then you understand yourself through this witnessing. It’s sort of like people who see Jesus on a piece of toast: I see a dog in a piece of wood grain or something. I think that’s a natural way for us to be in touch with what it means to be alive and aware. I like to see the dogs.

Were you ever discouraged from painting dogs?

Yes. I was told that I would never be taken seriously if I was going to paint my dog, or any dog. Especially as a woman. They’d say, “If only you would grow out of this” or “You’ll finally be successful, or interesting, if you let this go.” Mostly it’s male teachers. And also people that I respect very greatly.

Did you ever take it to heart? Was there a moment where you were doubtful and tried to do something else?

No. But I do a variety of different kinds of paintings, so they aren’t necessarily all super-direct dogs. There was a time, early on, that I wouldn’t paint very clear portraits of my dog. I was doing these weird, journeying tales of my wiener dog, and rats chasing her, kind of epic battles. So at that point in my life, people were like, “Oh, you’re doing little dog portraits.” And I was like, “They’re not dog portraits. That’s not what these are. They’re corporealizing paint,” and blah, blah, blah.

So, you were trying to intellectualize your process or theorize it in some way so that it seemed more legitimate or serious.

Totally. And then I was like, “No, wait, hold on. They kind of are [dog portraits].” At that point I decided, “Okay, I’m going to stop all the stories and then take away the paint, the extras, the zhoosh, and I’m literally just going to paint straightforward, old-school paintings.

I was also taught early on that you don’t have to have skill. You don’t have to be able to draw something well; that’s actually not interesting. Even when I was really young, I was always able to draw anything, but then I thought, “Oh, I don’t have to draw this way.” That was really generative for me, but then it was more generative at one point to think, “Yeah, but I still can.” I can do a very facile portrait of a dog, and it can be a very worthy thing. And it depends on what the context is with it. At the time, I was in graduate school at UIC [University of Illinois at Chicago], and it was a super-conceptual program, and I decided I would only paint very traditional dog portraits, shove them into this conversation about institutional critique, and other social practices or whatever, and I pissed people off greatly. But it was helpful to me. It’s helpful to me to always be a little oppositional.

What are you opposing lately?

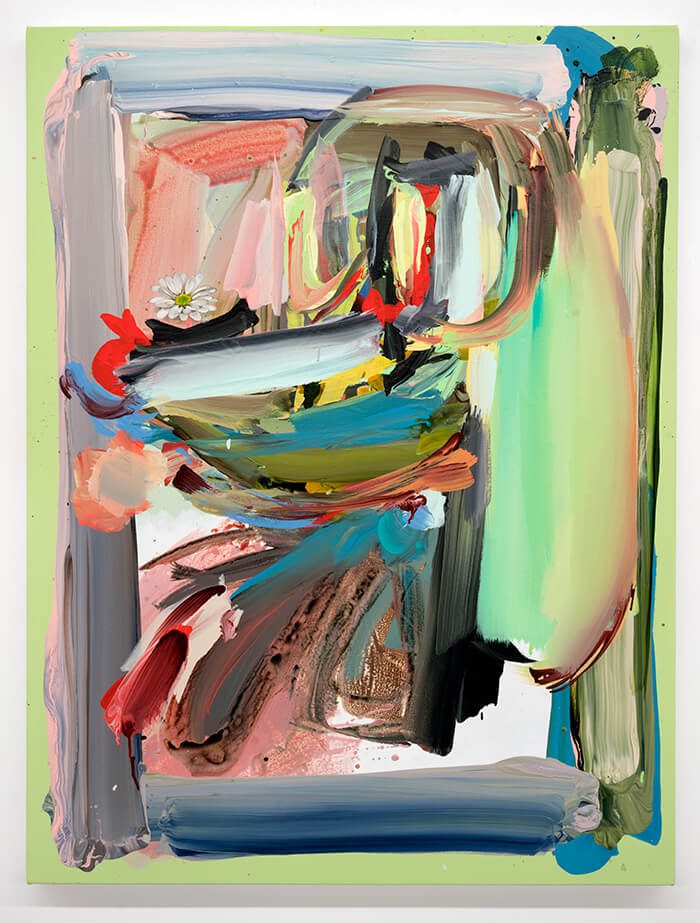

That is a good question. Let me think. . . I’ve been opposing being very naturalistic with my color choices. Usually my palettes are selected from looking at something, whether it be the sky over the course of five days, or I’ll look at a photograph of something to record all the colors. And lately they’ve been more intuitive, and aggressive, or garish. These are some of the brightest [gestures to the paintings on her studio walls].

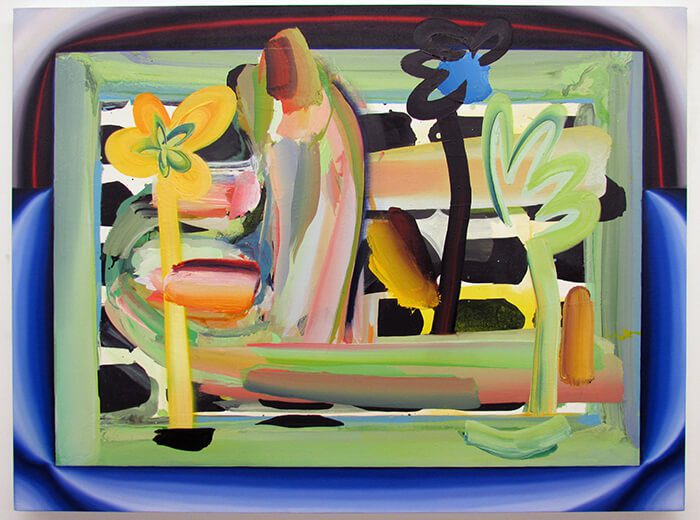

These borders that you’re doing remind me of airbrushing. I grew up in Alabama, so I used to go to the Gulf Coast a lot, and there were so many airbrushed t-shirts, and license plates, and everything. I don’t know if that’s something you’re intending to reference. I think it comes from the gradient around the edges of the canvas.

The gradient for me is more about old-school painting devices, areas around the edge that used to be naturalistic, kind of trompe l’oeil floats. So, rather than trying to create a frame of a narrow space behind the painting, so that it looks like a painting of a painting, and actually represents weird, narrow passages of space, I started thinking about creating that same kind of edge—but what if it didn’t depict naturalistic space and instead was pushing up against other areas? So the paintings are often called “Jammers” or “Yows.”

Yes, I was going to ask you about your titles.

Jammers comes from a couple different things. I had a friend long ago who would call one of my dogs a jammer. Like, “Oh hey, little jammer, jammin’ around!” So I started thinking about that dancing, funny, cute dog thing, but also what happens when you jam different kinds of space together, and squeeze something out of it in some way. And then a Yow would be like the Hound of the Baskervilles. They’re these stories about spirit dogs in the moors who come out of these uncomfortable spaces, and often the stories about them are not always clear. For instance, there’s this one dog story about Night Mallt, the Night Matilda. It has two different stories, but from the same town [in Wales]. One group of people believe that if you see the Night Mallt, she’s this red-eyed, horrifying banshee, who, with her horrifying black dogs, is going to take you to hell, and you’re going to die if you see her. But then another part of the same town thinks that if you see Night Matilda, she’s this beautiful maiden, and her benevolent white dogs are going to get you home safely.

I assume you have dogs.

I do. I have two. I just had one pass away in December. But most of the dogs that I do are modeled after dachshunds, or some kind of hound. My dachshund right now is named Bertie. She is not the character in these paintings, but she’s certainly my favorite, and Pickle was a dachshund too.

So, at this point are you creating a composite dog?

Yeah, and now the dog is more marks that come out of shoving different kinds of recordings of other things together, with paints on top of postcards, and photographs.

There’s also a lot more in your paintings besides just dogs. There are these areas of paint handling—

I’m super into paint. I love paint. Most of my paintings are really viscous and liquid-y, but I also really love the soft blended moments. This one is one of the first two Ophelia paintings that I did [Ophelia 1 (river jammer with cosmos and peas), see opposite page]. Most people don’t see the dog in this.

I actually did not see it until you turned it sideways.

So, Ophelia’s in the river, floating down the river, and there are these flowers. Honestly, I can’t say that I have a specific reason for its being Ophelia [from Hamlet]—It’s more related to that Millais painting [Ophelia, 1851–52]. There are moments in that painting where she’s in the water, and it’s beautifully transparent, but then there’s a perfectly placed little red flower, and little blue flower. But this didn’t start out like that; it just kind of turned into it at some point. I was thinking of this dog in a winter river—but also being in a garden box at the same time. Sort of grave-ish, but also not, because they’re suspended in a lively way. And there’s this growth involved with it. I’m an avid gardener, so my gardening tends to come [into the work] more now.

How so?

For me, that’s a place where I nurture life. And I would say, and my husband would also, that gardening’s probably my spiritual practice—I’m there, caring for something. And I think of painting a lot in the same way. So if I’m thinking about the energies of life, and the things that I literally look at every day, and the dog that I love, and those connected things, then it’s just going to end up in what I’m painting, because that’s what I’m painting about. The gardens started only since I moved to New Mexico, and I started going out into nature, and teaching a wilderness studio painting course. Then my paintings turned horizontal and went into landscape position. They were always in portrait position before that.

I want to ask you about your teaching.

Oh, I love it.

Especially since you had some pushback from your professors on your subject matter, what do you do to try to guide your students?

They know right away that I am oppositional. I try to encourage them and show them the possibilities around what they’re doing by showing them a bunch of artists who are really badass, of all different backgrounds, who are doing something that might look like what they’re doing, or who are doing something that might be thematically similar. I’m showing them that they’re part of this conversation now. But then I start picking them apart a little bit, but in a really friendly way. I would say that I’m probably one of the most encouraging and invested, enthusiastic teachers—but I’m not one of the easier teachers. I’m not aggressive, but I think it’s good. I think it’s productive to fight against your teachers.

You’ve talked before about the idea of painting as an act of care. Do you mean self-care? Or fostering empathy?

I don’t think it’s self-care. Painting is an act of care in that you are investing this time and energy into creating an object and an image and getting things just right, placing it how it needs to be. There’s an investment of time in that. I am working with ideas about images, and pictures, and what it means to exalt an image of something. Or to manifest that. And a painting is something that you hang on the wall, a special item that hangs there as a marker for something very important, usually. Or a place for contemplation, or pleasure. So it’s not self-care. Maybe it’s more of a compassionate or empathic caring for the thing, the image.

It seems like the act of painting and also the painting itself fosters a certain type of attention. And you can take that attention and apply it to other things in your life.

Yes. There’s an attentiveness, and an engagement, and a true connection or awareness that I think is beautiful. And I think people really understand that through dogs, too. Where else do you express such unabashed love and attention? You wouldn’t do that with people.

Yeah, it’s different when it’s an animal. I had a dog for years, and there would be moments where I would think, “I can’t believe that we’ve never spoken a word to each other.”

But you have.

Not verbal language, but there’s a language. There’s something really strange and amazing about that.

And it’s touch-oriented, it’s sight-oriented, it’s time-oriented, and it’s all things that paintings are. So, painting is a perfect place to maybe equate those things.

Jam ‘em together.

Jammin’ ’em together. Jammin’.