April 1 – May 8, 2017

5. Gallery, Santa Fe

Origins: Life Is a Lover. That’s a header that would normally bring in the curious walk-in as well as the veteran gallery goer. What makes it less likely for 5. Gallery is its out-of-the-way location, if by ‘the way’ for galleries you normally mean Canyon Road, the Railyard district, or the Plaza. The gallery is a short drive from the Plaza going south on Agua Fria, and a wrong turn can take you to Home Depot or Meow Wolf. So it might seem a stretch to compare a visit to 5. with what it might have been like to go to a start-up gallery in lower Manhattan, south of Houston Street, in the 1960s before it became SoHo. But not by much. 5. Gallery conveys a sense of understatement that pervades the space and anchors the consistent quality of the artwork.

A case in point is the recent group show titled Origins: Life is a Lover (April 1-May 8, 2017). While a small show, it managed to include an ensemble of work ranging from jade disks dating to the late Neolithic period, found photos from mid-century America, bronze sculptures from the 1980s, and works on paper by several contemporary artists. I use the word “ensemble” to imply that while each of these works can and should be viewed individually, they should also be seen as comprising a harmonic whole. In effect if not by intent, they perform as a group. Each work is a variation on a theme. To extend the musical metaphor, whether or not that theme adheres to the show’s title is of less import than how each piece in the ensemble varies it, whether to modify or transform its melody, tone, rhythm, or the harmony of the show itself.

The works on paper from Michelle Cooke’s Strata Series #6 (graphite, paper, plate oil, acrylic) from 2002-2004 yield a wealth of imagery through an economy of means. As with much of Cooke’s work, each drawing conveys an abstract visual force informed by a cryptic materiality that allows the viewer to engage the work at the formal or the narrative level, or both. Here, Cooke’s intuitive sense of line and form enables her to harness acrylic and graphite mediums to yield an exquisite visual phrase that carries the composition.

A spare counterpoint to Cooke’s pentimenti are the Zen-inspired 10 Way Drawings by Kerri Rosenstein. Equally elemental in their approach to subject and medium, Rosenstein’s pen-on-paper drawings take a more tectonic approach to matter and meditation. Each composition is shaped by markings made by linear gesture and weighted with a furtive density of geometric forms whose solid facets seem poised to migrate back to their fundamental role as shape and line. Rosenstein’s images function as pure form while insinuating matter: a shaded triangle slips into a shard, an acute angle morphs into an arrowhead, linear markings hint at hieroglyphic clues, and linear patterns conjure a larger pictography.

A kind of cosmic relief is provided by six jade Late Neolithic bi disks dated to the Xia period and attributed to the Qijia cultures of China. If the severe, unadorned, and perfectly circular plates attest to the emergence of order and dynastic succession in China, the little coiled and willfully cute “Zhulong Pig Dragon” from the Hongshan culture has to be the earliest imperial attempt at a playful rubber ducky to accompany a child emperor in the tub.

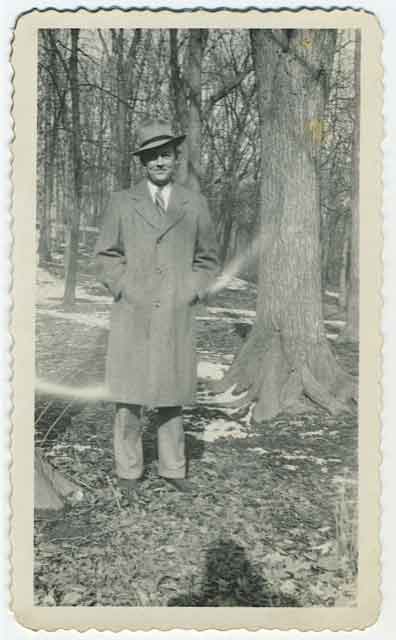

The found photos from the 1940s or later are typical amateur shots whose intent is simply to mark an important moment in a family’s life—the purchase of a new home, a holiday, an anniversary. Perhaps it is the semiotic hindsight of this postwar period—flush with victory and full of promise of the American dream and the good life—that lends to this lost family album a glimpse of the American tragedy.

The aura of the prehistoric Chinese jade disks and the meditative accent of Rosenstein’s 10 Way Drawings find resonance in the bronze sculptures of John Connell. Dharma-Chakra Buddha is an homage to Giacometti’s existential figuration in the service of Zen Buddhism.

Perhaps it is the semiotic hindsight of this postwar period—flush with victory and full of promise of the American dream and the good life—that lends to this lost family album a glimpse of the American tragedy.

Then there is a small oil-stick-on-canvas board drawing by Wes Mills titled Some mound, whose principal and singular purpose in the show is to illustrate that Buddha had a sense of humor.

And a less immediate yet credible link to the meditative cast of Origins can be posed for the selected letters of writer Kevin Law, who early on fled what he describes as “the cultural desert of modern suburbia”—the backdrop of the found photos—to go on the road in search of “writers like Rimbaud, Henry Miller, Hermann Hesse, Bukowski, and Kerouac … writers with a large sense of life who can put passion and vision into a book.”

Law’s literary conceit brings us back to the beginning, but now with new insight into the show’s title—Origins: Life is a Lover—an insight gained in no small part from 5. Gallery’s quiet dedication to quality art that provides engagement at the same time as it invites reflection.