Briana Olson mourns the theft of a King Tut death mask replica and confronts loss in a personal essay about mesh.

Someone had sliced open the screen that encloses the porch.

The tear startled me, flapping, a chink in my perspective. That was what drew my attention first, a subtle deviation in the texture of the landscape beyond the screen. I saw the torn mesh before I saw what had been removed: a plastic replica of King Tut’s infamous death mask.

I hadn’t considered Mr. Tut a guardian, a gargoyle, but in his absence the space seemed (and seems) vulnerable, exposed.

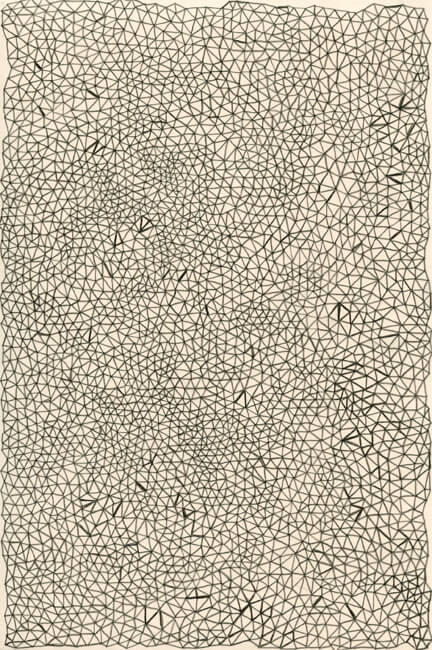

Mesh: a barrier constructed of openings, of interstices. The openings are tiny—not invisible, but recognized only in the way they permit one’s eyes to put together what lies on the other side.

Other uses of mesh: traps, trawling the ocean floors. Nets to keep out mosquitoes, disease. Straining over the kitchen sink: what seeps through is water. Air. The finest solid particles—sand carried in on lettuce leaves. The screen in serigraphy—filtering ink. Lacebark. Gauze. The scrim used to hide what actors do onstage between acts.

An interstice is a fragment of space, or an interval of time, which might be considered the same thing. An interval of space, a fragment of time.

The spaces between atoms may be interstices. Interstitial life thrives, unseen, between grains of sand. In the human, there is an interstice between the layers of the aortic wall. When the inner wall tears, as my father’s did, blood weeps into the interstice, expanding it, separating the layers of the aorta and interrupting the flow of blood to vital organs—the kidneys, in his case.

King Tut’s death mask is said to bear the likeness of Osiris, Egyptian god of agriculture and the afterlife. It was believed that kings preserved in his likeness would rule the kingdom of the dead.

“Why did this happen?,” my aunt asked the surgeon when he pulled up the scans of the dying world inside my father’s body, all of us assembled behind him, squinting at the torn vessel, the intestines on the screen.

In a dream, my father sits at his kitchen table, just the way he used to, except the table is outside, positioned at the edge of a wide green field. He listens hard, asks questions, won’t—never would—tell me what to do. He loathed the bossy gods, with their prescriptions and punishments, yet he was preoccupied with liminal space, limbo, The Evil Dead.

I do not believe that Mr. Tut rules the afterlife, or that anyone does, or that there is anything much there, that there is a there there. But how can I know with any certainty that the barrier between life and death is not also constructed of openings?

Perhaps the dead are also a form of transparency, a web of interstices through which we filter experience almost without noticing—until some force comes along, slices it open, and pulls what had belonged so fully to this side, our living enclosure, to the other.

My uncle tells me what a handwriting analyst said when presented with a sample of the crabbed print with which his brother, my father, filled dozens of legal notepads with songs. “A well so deep you could drop something in and never hear it land.”

The porch screen can be repaired, but Mr. Tut, silly as it seems, is irreplaceable.