Denver-based artist Joel Swanson’s obsessive processes explore how formal and corporeal repetitions function as methods of discipline.

Denver, Colorado | joelswanson.art | @joel.swanson

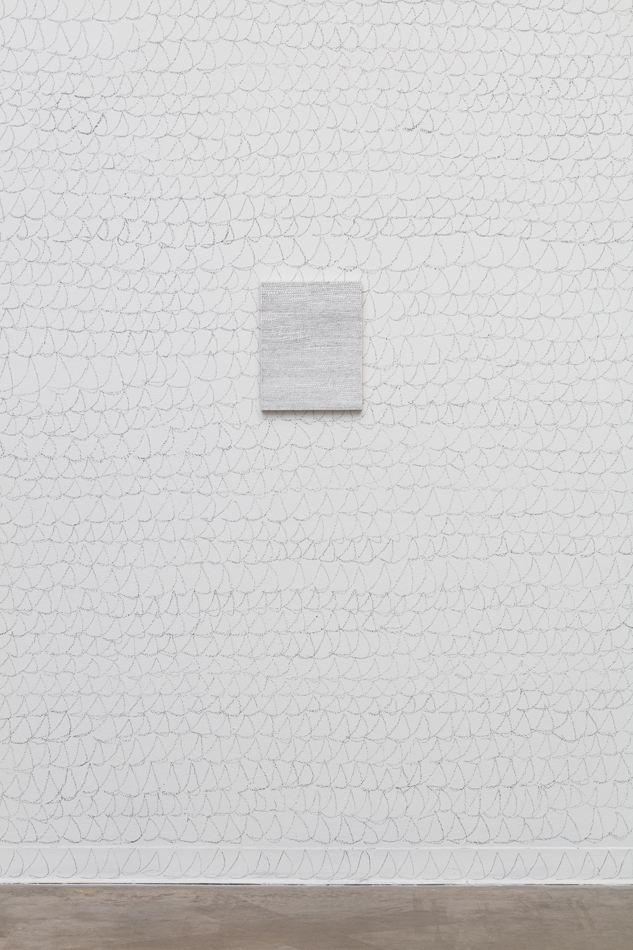

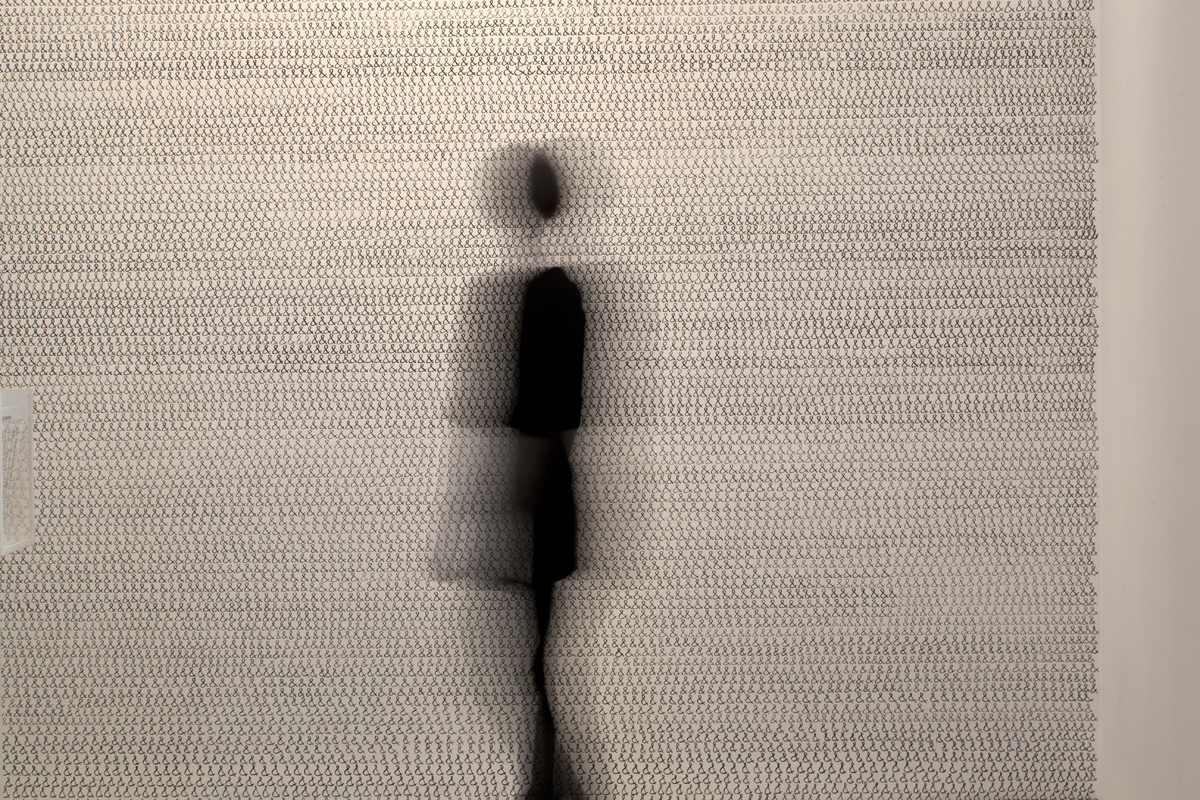

During the time-lapse video of Joel Swanson creating Cursive Lisp (2025), the Denver-based artist moves back and forth along a large white drywall surface—first on foot, then in a rolling office chair, and finally on a four-wheel dolly. Throughout this process, he scrawls from top to bottom a somewhat indecipherable mark across the length of the wall. From a distance, the piece echoes Sol LeWitt’s famous wall-drawings composed of vertically stacked lines within a prescribed area.

The conclusion of Swanson’s process clip, though, reveals something more than LeWitt’s abstractions. A hard cut near the video’s end jumps to a tight shot of the wall, subsequently zooming out to once more show the entirety of its surface. The close-up reveals a continuous series of the cursive “s,” one sliding smoothly into the next.

While the artist readily acknowledges that his work engages “canonical conceptual art,” such as the work of LeWitt, Swanson’s practice does more than rehash aesthetic and critical platforms from bygone eras. Instead, the artist challenges these previous frameworks to “excavat[e] the material culture of literacy acquisition,” interrogate “conventional systems of meaning,” and demonstrate how “seemingly neutral educational tools encode specific cultural values and ideologies.”

In the case of Cursive Lisp, Swanson asks the viewer: how do formal and corporeal repetition function as methods of discipline, control mechanisms, and tools that indoctrinate a body and mind into self-willed compliance?

But the artwork does not limit itself to these questions; it is much more expansive. For instance, the Lisp of the artwork’s title provides a nominal entryway into conversations about identity and issues attendant to the LGBTQIA+ community by tacitly invoking pronunciation stereotypes often associated with gay and queer culture. How have such identities and identity markers been subject to ridicule and punishment within our culture? Swanson’s use of cursive also gestures toward an examination of the destruction inherent to “progress” projects, insofar as technological innovation (e.g. typed print of digital screens) necessarily renders certain aspects of society obsolete and, thus, disposable.