Joel Swanson and other neon artists, with the help of Denver institution Morry’s Neon Signs, are fueling a new wave of neon conceptual art.

DENVER—Neon lighting, made by bending and filling hollow glass tubes with rarefied neon or other gasses, takes years to master and more often than not, an artist’s vision is brought to life by skilled fabricators.

In Joel Swanson’s case, Morry’s Neon Signs in Denver has become an essential part of his process.

“The biggest obstacle for me was feeling sheepish about having someone else fabricate my work,” explains Swanson. “I now know that working with studio assistants and fabricators is typical, but having other people produce my work required me to grapple with a new set of questions.”

Swanson is one of several area artists stewarded by Morry’s Neon—a nearly forty-year-old local business and the largest wholesale neon glass company in Colorado—who incorporate neon as part of their artistic practice. While Morry’s bends glass and fabricates neon into signs for local bars and corporate clients, they also work with visual artists who are helping to reverse the neon-as-dying-art stereotype.

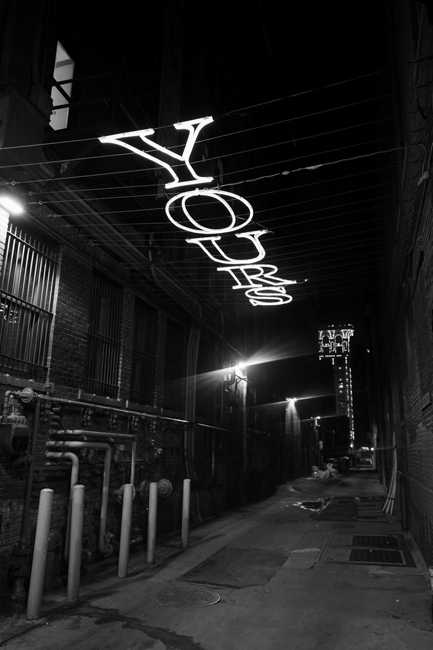

You might recall seeing Swanson’s piece Y/OURS hanging in a Denver alley a few years back. The work, which featured the “Y” blinking on and off every two seconds, was commissioned by the Downtown Denver Partnership and Black Cube Nomadic Museum for Happy Cities Denver, a citywide art intervention that took place in 2018. The artwork of Swanson, who has exhibited nationally and internationally, embraces neon’s unique warmth and its nostalgic echo.

“I’ve always loved neon signs, even as a kid. I have these vivid memories of going on family camping trips. I always wanted to stay in a hotel, so when we would drive by motels, I would longingly look at those ‘NO VACANCY’ neon signs to see if they had room for us,” says Swanson, who’s also an associate professor in the Atlas Institute and the Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics, and Society at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“I thought those signs were so clever—they could communicate the availability of a room simply by turning on two letters,” adds Swanson, who works in and teaches about the intersection of language and technology. “This idea that we can drastically change the meaning of words by playing with a few letters is a theme within my work. For all the specificity of language, it is still pretty frail.”

As an artist working in a specialized niche-like medium, Swanson has had to come to terms with the reality that he isn’t a hands-on part of the art-making process from beginning to end.

“What does it mean to put ‘my name’ on something that someone else made? What does it mean to use someone else’s labor within my work? When and where is my labor important? How do I honor and respect the craft and creativity that others bring to my work? These are important ethical questions that I revisit frequently.”

Swanson and Glen Weseloh, the owner of Morry’s Neon Signs, have developed a great friendship over the years. Glen’s father Morry took on neon bending after World War II through the GI Bill and in 1985 the duo opened the shop. The family affair has continued as Glen’s wife Tina and son DJ also work at Morry’s.

“My ideas can be rather complicated and I think they appreciate the challenge of working on projects that are outside the norm,” says Swanson. “They do great work and I’ve learned so much about the art and craft of neon from them.”

Though some would say neon is a relic of the past, Todd Matuszewicz, who has been bending neon at Morry’s with Glen Weseloh since the early 1990s, disagrees.

“There’s a movement of young people taking over,” says Matuszewicz. “Artists and experimenters are really pushing the boundaries of what neon is capable of, and though after World War II neon benders were primarily men, we’re now seeing more women and women of color jumping in. There’s a new wave.”

Artists like Roxy Rose, a third generation neon bender, and Mary Weatherford, the recipient of the 2020 Aspen Award for Art, are a couple of examples of how neon is now being pushed outside the boundaries of commercial signage—creating a diverse and lively community that is still buzzing.

“As many people are turning to LED tube lighting for a less expensive, but similar effect, it has certainly become more of a bespoke art and craft, but I think neon will never completely fade away,” says Swanson. “There will always be devotees who keep these practices alive and well. As an artist, it is a privilege to work with these people who are so dedicated to their craft.”

Last year, Swanson was invited by the New Collection, which recently showcased Mario Zoots collage work, to participate in a project-based arts initiative that gives artists permission to play and “push to do something fundamentally new that they otherwise wouldn’t have done.”

It became an ideal showcase for exploring Swanson’s solo exhibition The Distance Between Words, which includes his piece Frequency Adverbs. “The installation is beautiful, especially at night,” says Swanson. “It is mesmerizing to watch the words blink on and off in this strange semiotic constellation.” You can explore the exhibition through April 15, 2023, at The Vault, 3758 Osage Street in Denver. Swanson will also have a solo show in 2024 at the new Foothills Art Center in Golden, Colorado, where he plans to include some new neon works.

“There is a rich tradition of using neon in conceptual art—[Joseph] Kosuth, [Lawrence] Weiner, [Bruce] Nauman. I want to situate my work within the lineage of conceptual art, but simultaneously be critical of that tradition. My work is often playful, sometimes absurd, and I hope that comes across as a critique of the seriousness and exclusiveness of conceptual art.”