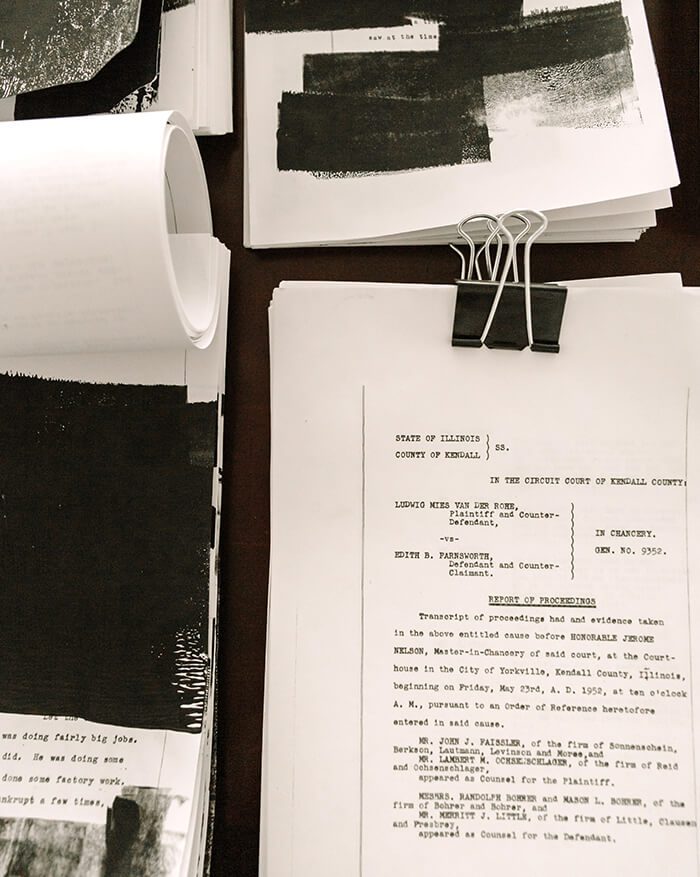

In Nora Wendl’s downtown Albuquerque home and studio, morning light filled each cozy room on the January day we visited, illuminating a myriad of projects. Across the upholstered cushions of her couch, chapters of her hybrid memoir and architectural history book-in-progress were stacked. On her dining room table were nearly four thousand pages of a courtroom transcript that she is working with to create an installation for a 2021 exhibition, blowing up lines of the text to exaggerated size. On her desk, fanning out over the keyboard and wood wings were dozens of reference books that she is using to recreate a tour script. On the desk, as well, were the schematics for a glass house in the Midwest and black-and-white photos of a singular woman whose life has created a jumping-off point for Wendl’s recent cycles of work.

That glass house is the Farnsworth House in rural Plano, Illinois, named after the woman who commissioned it, Dr. Edith Farnsworth. The house, on the banks of the rapidly encroaching Fox River, has a reputation that precedes it. Its innovative design was displayed at MoMA ahead of its construction in 1950, helping to secure German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s reputation in the U.S. The building—a 1,500-square-foot, one-bedroom retreat, some fifty miles from Chicago, is constructed of glass and steel, the result of creative synergy between the architect and the woman it was designed for.

Farnsworth was among the vanguard of her era. In a time when there were limited positions for women in medical schools across the country, she rose in the traditionally male field (after briefly considering a career as a concert violinist). A poet who spent her free hours at her music stand or translating Italian texts, she gained recognition for her research that led to a cure for a once-fatal kidney disease. She met Mies van der Rohe at a dinner party in the summer of 1945, later commissioning the house, now a destination for International- Style architecture enthusiasts. Though the results are famed, the venture was ill-fated, resulting in an overextended budget, rumors of a love affair, a lawsuit, and an anemic historical narrative that doesn’t capture much nuance. Wendl, a trained architect and an associate professor in the department at the University of New Mexico, has made it her project to—in earnest and expansive ways—delve into the history of the glass house and the woman who lived there. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Maggie Grimason: How do you think of yourself—as an architect? A writer? An artist?

Nora Wendl: That was one of the first things that someone asked me when I started teaching and having my own body of work—are you an architect or a writer? And I thought, “Do I really have to choose?” So many architects—especially the ones that we know—were prolific writers. We always think of architects as builders, but the ones that really get remembered are the ones that did a lot of writing. I think I’ve been writing a lot through visual and performative relationships with artifacts from historical moments, so I’ve been thinking about how you label what you do. I think maybe instead of labeling via discipline or object or what I’ve been making, I’ve started thinking of myself more and more as a historian. I’ve been really inspired by Hayden White and his book, The Practical Past. His argument is that there is no actual historical account of the past. You can make a story about it, and that’s what we do as people. It’s all totally subjective. The historical past is what actually happened, and we have no access to it, and the practical past is how we understand the past through our experiences, our situation. I think, more and more, I’m interested in what it means to create histories.

How does that make you feel in terms of your work on Dr. Farnsworth? Does it feel like a huge responsibility?

It actually feels really liberating. If we start from the premise that history is something we’re making, then I feel really liberated. I’m a flawed human making another flawed history. And we’ve had so many flawed histories that disadvantage women, that silence women, people of color, queer folks. History has always been a sort of erasure. If you enter into it saying I’m a historian who enters into it embracing the flaws of the process, then I actually feel much more liberated saying I’m a historian than saying I’m an artist or a writer.

It can open eyes to the fact that anyone can do this, too.

We all get to be historians! There is no actual truth. If we embrace that, it undoes a lot of the most problematic aspects of being an academic, being a historian, being in a body that is already politicized, already disadvantaged from the minute you arrive anywhere where the professional context expects a man. I’m so over apologizing, starting from a premise of apologizing for the neutralized idea of what my profession is. I think we’re at an exciting moment where we are talking about that more openly. The idea to say I’m a historian came out of this desire to be brave, unafraid to say, I don’t have a PhD in architectural history, I don’t have the professional credentials to literally call myself a historian. But the practice that I’ve been engaging in has been to break down historiographic methods themselves—to ask: How is it that we construct history? How do we choose the sources we’re using? Why is it that sitting in a historical space and occupying it, why can’t that be considered a way of understanding history? Even unpacking the gender dynamics of my dealing with an archive. That’s history. I can’t have access to something—sometimes access is made trickier because of gender.

Which speaks to who has access to the future and who shapes it. How does that influence your work looking into the past at the Farnsworth House now?

For one year, the National Trust is focusing on narratives of women and the places they commissioned or built. [It’s called] Her Turn. So I’ve been working on re-staging her house. I’ve been really struggling with what does it mean to just stage artifacts? With no subtext, no interpretation, really. Her life is an interesting mystery to me. There are all these questions about her and how she conducted her life. For me, that’s the part I’m more interested in—who she was. So, approximations of her things are cool, but I’m more interested in: What did she read? What did she think? What did she smoke? Who did she have over?

I keep thinking that, since she was a poet, all the metaphors of being a woman living in a glass house cannot have been lost on her.

She was constantly dealing with metaphors. And these were very verbose poems. A lot of them have to do with silence, voices, houses, reflections. She was really thinking about the material world in her poetry. And the psychology of living in a glass house! You’re either totally exposed or [with the curtains drawn] completely cocooned. You’re exposed, or you’re seeing yourself. And she was super alone. But she did it. She lived there Wednesdays and weekends. To be so alone, so exposed, and just be like, “Fuck it, this is my house and I paid for it.” There weren’t even highways. Now it would take you fifty minutes to get there [from downtown Chicago], but then it would’ve taken closer to two hours. It was all gravel roads, beautiful but very isolated. I’m so impressed with her.

A lot of this—the design of the house, the furniture, her research—it’s all about innovation, and being on the forefront.

Absolutely. She was a pioneer. She took risks, and the architect is the same way. I think perhaps that is what they saw in each other. She writes about that in her memoir—the excitement of the summer of 1949, where she’s making advances in her research and Mies is starting to design this really unusual house, the house that launched his entire American career. Both of them recognized the other’s genius and talent. In the end, a lot of historians speculate that they were lovers and they had a falling out. I think it really came down to [that] she paid him seventy grand—and for context, in the 1950s, a house was five thousand dollars, so that’s sixteen times the market average—and she wasn’t even sure she could live there. Male historians are like, “I don’t get it. What didn’t she like? This house is crazy!” And the house leaked; the interior flooded. Of course, she was pissed. But it was also an unusual time to take an architect to trial [Mies sued her for unpaid expenses after the house was completed; she counter-sued]. It was 1951: women couldn’t even serve on juries in the U.S. until 1955. In the end, the judge says, “I can’t enforce any of this because you don’t have a contract.” It was over for almost no money; yet, for whatever reason, the received history is that Mies won the trial.

It underlies what we were talking about before—received histories aren’t accurate. And it’s not as romantic as the official history would have us believe.

It’s the opposite. It’s so banal. The courtroom transcript is four thousand pages—it’s four thousand pages of serious banality. And seriously absurd. They bring in an expert on glass, for example. And they say, “Tell us how light moves through glass.” It’s a very technical document to the point of absurdity, which is what I kind of love about it.

These various elements of this story have held your interest for so long. Have you discovered new things along the way, and has there been self-discovery as well?

I think so. I think it is, in part, a self-discovery. I started to realize how weirdly narrativized [Farnsworth] has been, weirdly maligned. Like, the way she was described in history books: people described her as ugly. There was this focus on the primary narrative of the history, and I got way more interested in who she was as a person. I find her endlessly fascinating. Like, reading the court transcript, for example, she snaps back at judges and doesn’t care what anybody thinks. She’s larger than life. Her presence pervades all of these documents. I keep finding new stuff and thinking, “This is part of the history of this house and this person, too.” It surprises me how much stuff there is to draw history from and how little has been drawn from it. This [work] has carried me from being interested in the history of buildings to making me realize that there’s something inherently still quite sexist about my discipline and the way history in my discipline is written. For me, it’s opened up a whole new practice of thinking through art production as a mode of authoring history. It was the vehicle to get me from thinking really distinctly about art production and women’s lives and humanity and history and writing. I used to think of those as different things, but the project has gotten me into this space where I think they’re fully integrated. And I think my practice does that. I’ve been writing throughout the last year or two, and now I feel like I can kind of finish it and it’s not really about the subject anymore but about what the subject has allowed me to practice.

Do we all have these rich, complicated relationships with structures?

I feel like you’re always in this place of beloved vulnerability with architecture. You have to make a place; you have to make it a home. I think of living here as a collaboration with the space that I’m in. It feels really important to me to have a comfortable, trusted space to work in. I trust this place, and I think there’s a mutual exchange going on. At the same time, it’s very vulnerable: it’s not mine. I’ve tried to come to terms with that—and I think a lot of us have—that, increasingly, who can afford to buy property? It’s really difficult, and a lot of us move frequently. It’s just become the reality of our world. I think we all have very personal relationships with places. I think that’s why a lot of people become architects. I don’t think we spend enough time talking about that sort of autobiography, the personal relationship to space and place. It’s such a critical part of how we think about architecture—it’s the poetics of inhabiting things.

I’m interested in your book—which I’ve noticed is titled Glass—and I wonder how that as a material, as a metaphor, has functioned in your life and in this work?

I think this is something I started to realize as I was writing: we hear a lot about a glass ceiling—advancing and advancing and you can’t get past it. What I started to realize is that what I’ve experienced is more like a glass wall. Maybe it is our generation, but I feel like we’ve moved past the glass ceiling and we’re behind a glass wall. You see people moving ahead, you see women CEOs, but it’s like we’re in a parallel reality with men. We have different experiences. Everyone can see us—from the outside it doesn’t look much different—but we’re in a completely different world. For me, it’s a much more insidious metaphor. At least with a glass ceiling, you know where your limits are.

What do you see as ideal futures for this house? For your work with it?

For me, the ideal would be that the work disrupts the historical juggernaut of how we’ve been writing this history. I want my work to interrupt and question all the preceding histories. History is basically text and images, and I really want to introduce a stuttering, multi-faceted, fragmented, questioning, gendered, messy, wrong, and very personal account. If I can do that, I think it would interrupt the way this has been historicized and also welcome other people to think of themselves as historians, to realize [that] they have the ability to historicize their lives and that we belong to history—you get to interrupt and play with it. It feels urgent to me to fix this narrative, because in one more generation, why would anybody care? Why does this cool house matter? Ultimately, the question about the house—right now they are trying to figure out how to protect it. There’s been so much development in that area, there’s nowhere for the river to go, so it goes to the floodplain where the house is. They are considering putting it on pneumatic lifts so that as the river rises, they can raise it. Given the structure and its age and how it is put together, they can only lift it eight feet. Climate predictions suggest that would save it only for the next three to five years. And it would cost millions of dollars. I personally feel like it would be amazing if they let the river take it. There would be something really poetic and beautiful about letting the river take it over. You could drive through and see this glass house full of water. It would be beautiful.

This issue’s Studio Visit is sponsored by form & concept. All editorial is directed by The Magazine and its bylined contributors.