Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

May 2 – 27, 2018

Late in the process of making artwork for her solo exhibition, Within This Skin, Nikesha Breeze started a series of ceramic and oxide wall sculptures titled Written in Water. She calls the works “death masks,” and each coppery visage was originally molded from her own face. After adding her impression to a blanket of clay, Breeze would stretch and carve the medium, emphasizing some of her features and shifting others. Here, her nose extends and nostrils flare; there, her cheek bones flatten. An eye vanishes under scar tissue, and fine wrinkles cascade down a forehead.

The Taos-based artist is on a tactile search for her ancestors, rethreading her genetic expressions over and over in pursuit of intrinsic knowledge. As indicated on a wall tag, Breeze plans to create 108 masks—a reference to a number that surfaced several times in a wide-ranging research project she initiated three years ago. “I was looking at the mass movement of the slave trade in the first few hundred years of slavery in the United States,” she told me on a walkthrough of the show. “Going all the way back into the African villages where people were killed and kidnapped, the death toll became massive. It was 108 million people, the largest genocide on the planet.”

Seven masks appear in Breeze’s show, the first ever solo presentation by an African American artist in the Harwood Museum’s ninety-five-year history. The faces are clustered on a sliver of wall in the institution’s Studio 238 project space, a prologue to a grouping of large-scale mixed media paintings that fill the rest of the diminutive gallery. Breeze’s process of sculpting the masks mirrors the larger arc of the project, which has required her to flow between evidential investigation and deeply intuitive discovery.

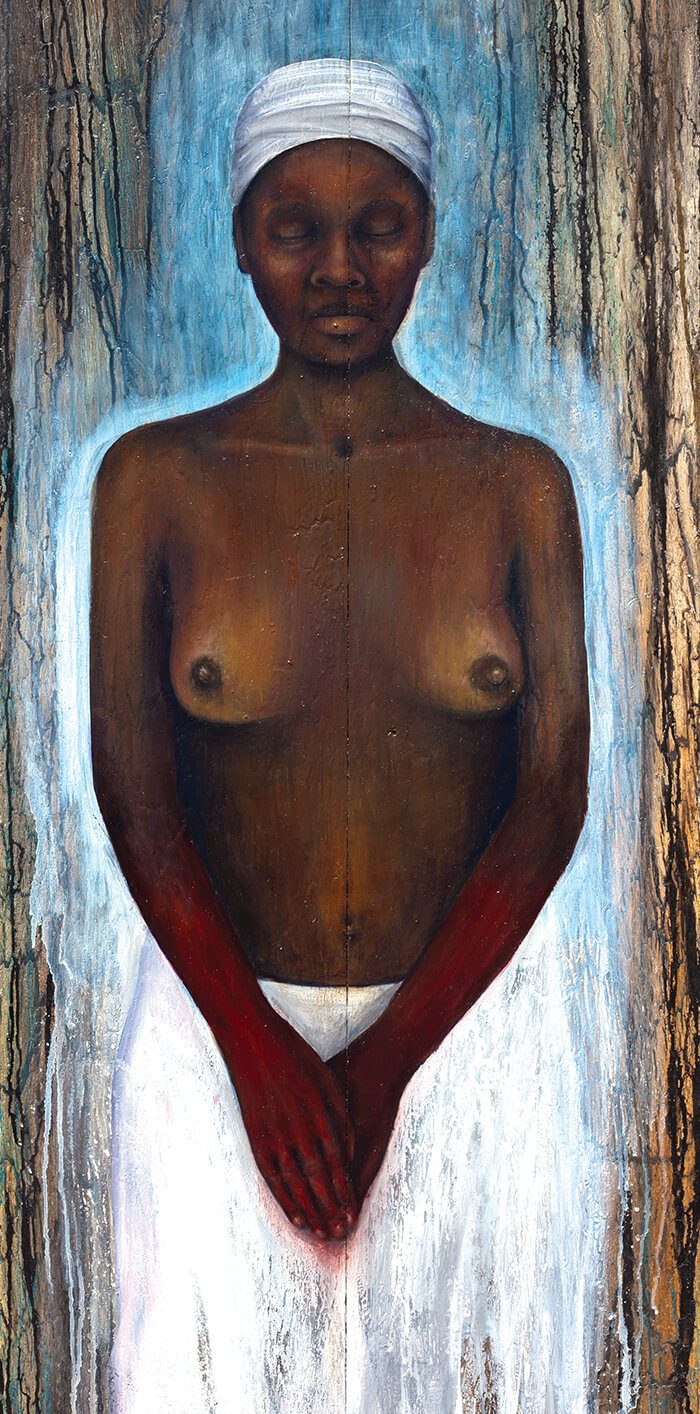

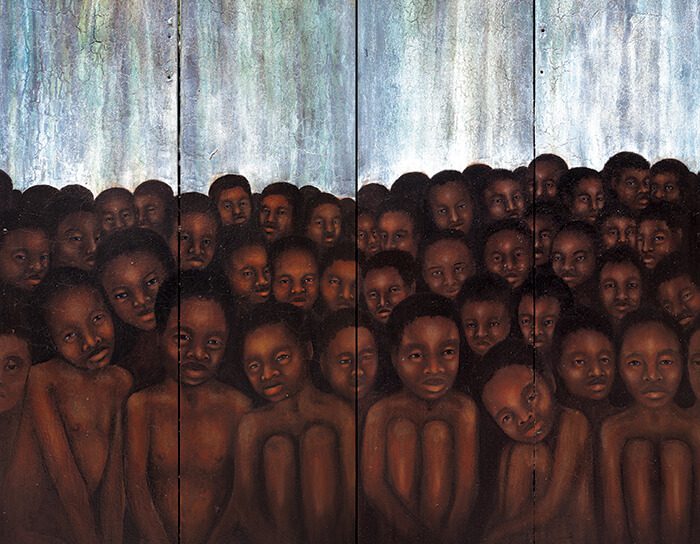

There are seven paintings that make up the bulk of the show. They’re painted on closet doors salvaged from Habitat for Humanity, a choice that was both practical and conceptual. Breeze prepared the unprimed wood by sending rivers of oil paint and black ink cascading across it. She added wax and dry pigments to create densely textured abstractions with their own river-like topography.

Atop this ground, Breeze applied countless layers of oil pigment, depicting Black figures that started out ghostly and eventually leapt into crisp focus. Among them is a grandfather with a delicate bruise on his cheek, a grandmother whose hands are stained by afterbirth, a lynched man hanging in a sunlit forest, and a child standing face-to-face with hooded Klansmen. The tight arrangement and human scale of the works gives them the feel of actual portals, evoking the sensation that one could tip straight into these enmeshed stories of life and death, tragedy and survival.

An early point of inspiration for the body of work was the Langston Hughes poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” “I’ve known rivers: / I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins,” it begins. “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” Though the poem is written in the voice of an old, wise wanderer, Hughes penned it as a teenager on his inaugural voyage away from his birth state of Missouri.

When she first read the poem, Breeze was working towards a career as a plastic surgeon focused on gender reassignment surgery at UNM-Taos. Apart from her studies, she had immersed herself in an investigation of her heritage, something that she’d never explored growing up in “a very white, very redneck” corner of rural Oregon. “Learning the story of my Blackness has come late, but like Hughes did, I’ve felt these rivers,” she said. “I traced back through my great-great-grandmother, who moved to Blackdom, New Mexico, from the Carolinas. She was a freed slave who came out West.” She couldn’t find her way back much farther than that, but what could have been a dead end became a bridge to broader studies of Black history and culture.

Images of people who looked like Breeze surfaced in her mind, and she began painting and sculpting them. Breeze built a decades-long career as a performance artist and arts educator, with small forays into sculpture and photography, but she had never tried her hand at painting. The extracurricular project eventually led her to shift the focus of her studies at UNM-Taos to the fine arts. That’s how she went from learning how to reshape bodies for the purpose of gender confirmation to sculpting her own features for her first major solo exhibition.

Within This Skin might occupy just two stretches of wall, but it’s a staggering statement that simultaneously references history and lives in the present. After all, as Breeze pointed out on our tour, all of the atrocities depicted in the paintings have modern-day analogues. Case in point: we’re approaching the one-year anniversary of Charlottesville’s white supremacist rally and counter protests that ended in murder. Breeze’s figures possess the knowing look of ancients, but they are far from archetypes. They are our contemporaries.