May 16, 2017, 6 pm

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center Conversation with Fellow Janet Catherine Berlo

I first met Janet Catherine Berlo when she invited me to her home for dinner. It was 2009, and I had just arrived in Rochester, New York, where she is Professor of Native American Art History in the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. I shared much more over the course of the next seven years as she became my doctoral advisor, mentor, and friend. Janet is currently Research Fellow at the Georgia O’Keeffe Research Center and will present a talk titled “Mimbres Multiplied: Ancient Pottery and Modern American Visual Culture” about the complex history of indigenous appropriation.

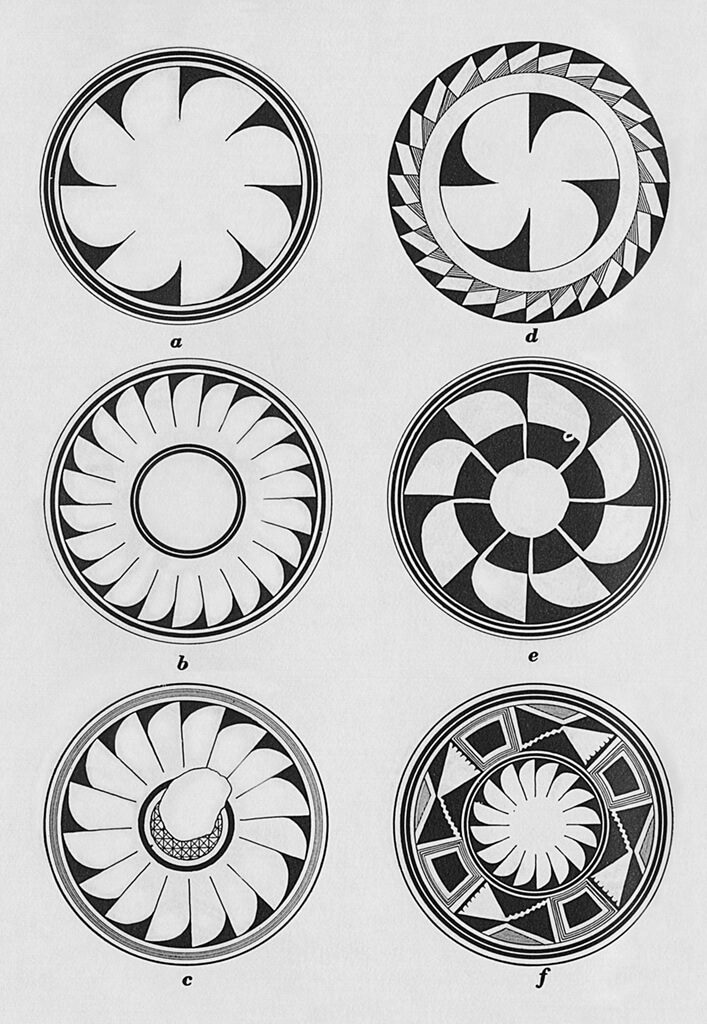

Alicia Inez Guzmán: Your upcoming talk touches on the popularity of Mimbres painted pottery on an American design sensibility. How have these historical forms been integrated into new media? Why do you think this was and continues to be the case? Janet Berlo: One very simple answer to “Why?” is that the Mimbres pottery painters were amazing graphic designers. The way they combine abstraction and representation really appealed to a modern twentieth-century design sensibility, and that shows in the way that Mimbres objects were installed in 1941 in the legendary show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Indian Art of the United States, as I’ll discuss in my talk.

In the mid-twentieth century, Mimbres designs were used in Mary Colter’s china for the Santa Fe Railroad. But it also provided inspiration for fabric designers and jewelry designers. And, of course, Native potters from Acoma and San Ildefonso have incorporated Mimbres designs into their pottery painting for half a century now. Some, like Charmae Natseway, do so in really original ways. And everyone in Santa Fe knows the amazing work that artist Diego Romero has done over the last twenty-five years, using a Mimbres style to comment on modern life.

I know that this lecture relates to a broader book project, titled Not Native American Art: Replication, Misrepresentation, and Other Vexed Identities. Can you talk about how you first started thinking about fakes, forgeries, and “vexed identities” in terms of Indigenous visual heritage? For me, this started when, about a decade ago, Sotheby’s in New York successfully sold a book of allegedly “Rare Hidatsa nineteenth century ledger drawings” that many scholars in the field (including me) had told them in no uncertain terms was not made by a Native artist and did not date from the nineteenth century. This got me to thinking about the inexorable need the market has for the old and the rare.

Then I kept hearing people talk about nineteenth century war shirts sold for record-breaking prices at auction, shirts that some experts believed had been egregiously over-restored. I realized that people talk about these things, but no one ever writes anything about them in the field of Native American art history. So then I spent ten years accumulating material, talking to people who make historical replicas, and talking to museum curators and art dealers about forgeries and objects that have been over-restored.

To me, that about sums it up. In my opinion, and in my experience working with both Native and non-Native artists, most artists are magpies—their eyes and brains are always hungry and are adapting visual imagery from here, there, and everywhere.

Cultural appropriation has become a much-debated topic recently. Do you see the Mimbres material you work on—or other examples in your project—as instances of direct appropriation, or are there other forms of intercultural exchange and collaboration that we should be thinking about, too? As I’ll show in my talk, the Mimbres material has been directly appropriated and reused for nearly a century now. Conveniently [for some], there are no direct descendants of these people who lived and worked a thousand years ago to protest this. (Not that anyone in the 1930s or ’40s thought that there was anything wrong with this. They saw it as a modern way of thinking about being American, using Indigenous sources rather than the old tired artistic sources from Europe. Now, of course, we see it as far more problematic than that.)

One of the things I am trying to wrestle with in my larger book project is the simple-minded narrative that separates “Indian art” from “Hispanic art” from “Anglo art” when all of these people have been in profound contact for centuries. Of course, under settler colonialism, the power was mostly in the hands of the non-Natives. But when we look at visual culture, it is not easy to make dividing lines about what belongs to “us” and what belongs to “them,” no matter who “us” and “them” are.

Over my desk at the O’Keeffe Research Center, I have pinned a quote from anthropologist Nick Thomas, a Brit who has worked for decades in the Pacific region. It says, “Artifacts are promiscuous.” To me, that about sums it up. In my opinion, and in my experience working with both Native and non-Native artists, most artists are magpies—their eyes and brains are always hungry and are adapting visual imagery from here, there, and everywhere. Pueblo potters and jewelers have been doing that for centuries, for example.

How do Indigenous definitions of “copyright” or intellectual property differ from our modern Western understandings, and do those impact how you approach your topic? There are many different Indigenous conceptions of “copyright.” It is not uncommon, on the Great Plains for example, from the nineteenth century to the present, that one “owns” a design that may have come down through one’s family, or it may have arrived in a dream. It is extremely bad manners to use someone else’s design. But if one asks permission, and if payment is offered, the rights may be shared. Last year a well-known Lakota beadworker told me he had visited Jamie Okuma, who was the first one to bead high-heeled shoes and boots. He brought her a blanket as a gift and asked her permission to embark upon his own pair of beaded high-heeled shoes. She readily granted him permission. It is all about making a diplomatic request and acknowledging someone else’s prior creativity.

It seems that ideas about “authenticity” play a rather significant role in how we interpret Indigenous objects from the past and the present. Is “authenticity” useful? Is it flawed? Both? Whenever I hear the word “authentic” or “authenticity,” I picture someone dragging a battered old suitcase crammed full of outmoded ideas.

Here in Santa Fe, shop windows are full of what the marketplace thinks of as “authentic” Indian art. A lot of it is an endless recycling of nineteenth century images and motifs—images that were fresh and new at one time. But Native art is and always has been endlessly inventive. Always incorporating the new. But far too many members of the general public have this fossilized idea of authenticity. And as many, many Native artists and cultural commentators have said for decades now, an outmoded paradigm of “authenticity” puts a straightjacket on Native creativity.

In one sentence: authentic Native art is something made by a Native American person. Period.