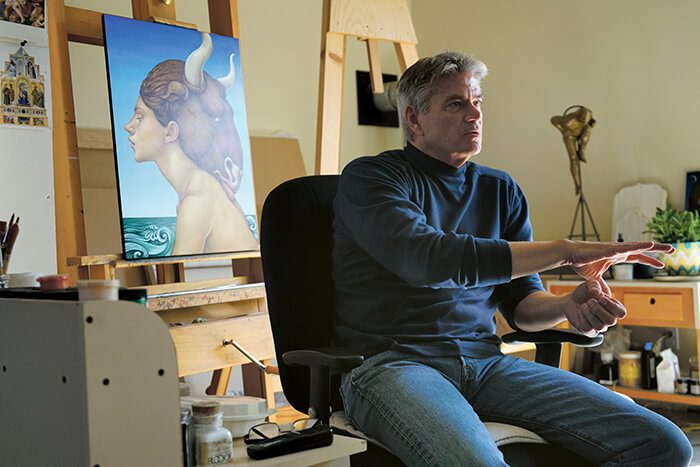

Michael Bergt has been in deep dialogue with art history over the course of his more than thirty-year career. Working across drawing, sculpture, and primarily egg tempera painting, Bergt has engaged art’s long history of grappling with representational and abstract sensibilities. Inspired by the early Renaissance, classical mythology, and other diverse religious and spiritual imagery, his artwork represents his own play with expression and interpretation of the contemporary human condition. While grounded in these art historical and visual traditions, Bergt also profoundly breaks from these as he creates his own cast of mythic characters, with their own poetic inclinations and relationships informed by modern dialogues around pressing topics such as gender and sexuality.

Lauren Tresp: You have said you knew you wanted to be an artist when you were five years old. Have you been an artist your whole life?

Michael Bergt: I’ve been very fortunate. I had my first show in San Francisco when I was 24 years old. That show sold out, and I never looked back from there. And that’s rare. I was born in a small farming community, and where I got the idea, I have no clue. But I was always drawing since I was little, and people would ask, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” And I said, “I’m going to be an artist.” You know, you’re quite often too naive to know [something] is impossible, and that sort of keeps you in that line. Because if anyone had said, “No that’s impossible, you can’t do this,” then I would have done something else. But obviously I didn’t fall in that pattern.

LT: Has the style of your work changed tremendously over time, or were there roots that were laid early on?

MB: In any career that has lasted over three decades, you’re going to have some evolution happen. It’s also that arc of refining your technique and what it is that you’re interested in. I’ve always been sort of craft oriented, and very methodical, precise in my rendering, so I’ve always looked toward the early Renaissance as an influence or inspiration. That’s the source of the kind of work I have always wanted to emulate, but it doesn’t mean I’m turning my back on contemporary art, or I don’t acknowledge it, or I don’t want to imbue my work with things that I feel address contemporary issues. I’m not lost in the early Renaissance of the 14th century.

I like the idea that those are two discrete ways we understand the world around us. We either make symbols of it, or we make very precise renderings of it

LT: Did the time you spent living in Spain have anything to do with that?

MB: Actually, I was working in egg tempera before I moved to Spain, but what Spain gave me was a different cultural experience. It got me to Europe and to live with a different language, different history. Also, the rest of Europe is so available once you’re there: within a couple hours you can drive or fly to visit anywhere. A couple of times a year we would just head out and visit France, drive around Spain, visit Morocco. It was a great cultural experience.

All I was doing was painting for that time. I used to call it my “backfill” years, because while I was there, I would go out every day and do watercolors on locations, studying everything: landscape, interiors, and people. I was filling my reservoir of imagery, the effects of light, technique. After that, I had this whole cache of information all ready. So I went through a period where a lot of my work was kind of invented; I would invent scenarios and people. That switched when I began to work more and more from life. Once I began working from life, that really changed a lot of narratives, because you can’t take the real figure and put it in an invented narrative the way you can [put] an invented figure into an invented narrative. The whole dynamic began to shift in terms of how I was going to create a dialogue with that figure and say something metaphorically about what was going on. That has evolved over time.

LT: You mean the grounding or framing of it changes?

MB: There’s a certain aspect of being grounded in representational reality, and then how do you launch it from there? It becomes more precarious creating the narrative around it. One of the things that I began to play with was the idea of two-dimensional patterning—symbolic representations of elements—and then a much more three-dimensional, western lineage of perspective and verisimilitude. For a period, I was combining both within the same painting because I like the idea that those are two discrete ways we understand the world around us. We either make symbols of it, or we make very precise renderings of it, and they are both ways of how we reflect what we think about the world. If you could somehow put those two things together, you actually create a more comprehensive sense of how the human mind understands its environment. So that was a lot of that blending of east and west. I did a whole series around shunga, which are Japanese prints. I saw that as both the flat patterning symbolic element that has something to do with psychological, internal representation, and then a drawing representing a person having this dialogue within themselves, and having them both combined in the same image.

LT: Do these concepts come from topics that you’ve studied?

MB: All of this just starts with asking, “What are you fascinated by? When you look at art history or you go through museums, why are you fascinated by certain painters, certain periods, certain styles, certain images?” Then start tracing that thread, and when you start pulling that thread back, you realize, “What I like about this is that it says this about how the world feels to me.” And then you ask, “Well then, how do I say that about living today in this world? What fascinates me?”

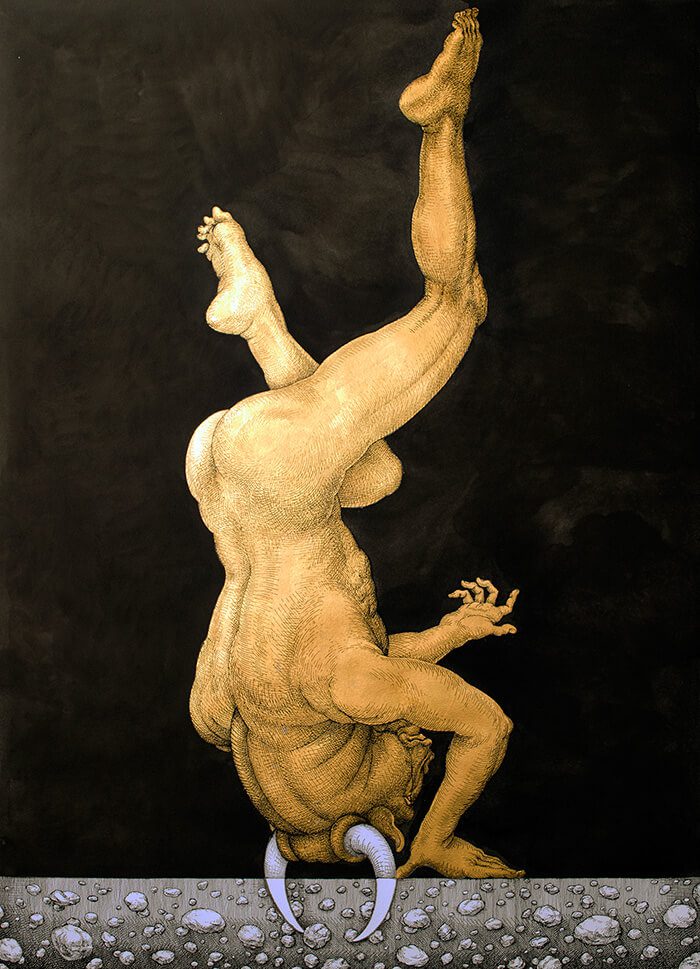

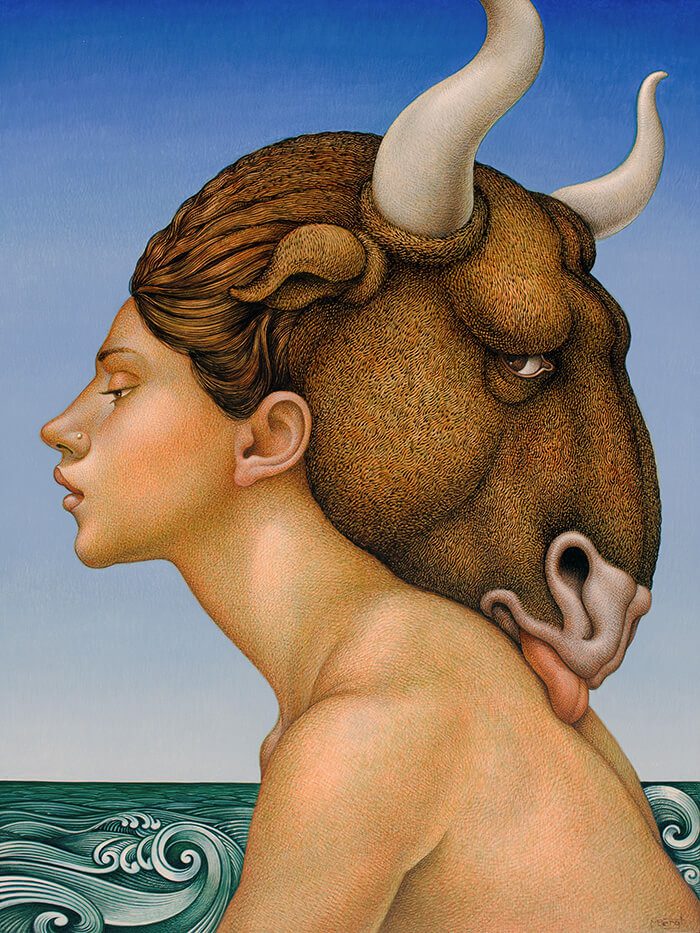

I’ve been doing this whole series on the Minotaur, and for years I’ve been playing with Leda and the Swan, classical mythology, and the blending of human and animal characteristics. Now it is distilled down to this idea of masculine and feminine polarity. If we look at contemporary life, what I perceive is that we see this evolution and empowerment of women, and there’s this bigger polarity in the feminine realm, but then what is matched in the masculine realm? In some ways it has become more ambiguous about what that polarity looks like. And when you lose that polarity you lose a lot of the energy, that tension that happens between the two. So how do you then expand upon that to make it kind of exciting again, and more vibrant?

I guess what I want to say more than anything is that I don’t see anything irrelevant about using these ancient techniques or iconography to address something that is very contemporary.

A lot of people have said that my female figures tend to be very powerful, either very athletic or self-possessed. So how do I match that with a masculine element? Suddenly the Minotaur became a great foil. The narrative that happens between the two of them, the sort of dance that they have between them, is one that is completely different from the historical stories—he’s not just grabbing her and hauling her off; they’re actually having this dialogue. There is an interaction, a negotiation to see who is going to invite whom to be acceptable to what—which is very much, as I see it, contemporary life. I’m just having a great time playing with this dance and seeing the reaction and seeing people saying “What’s the next one, what will they do next?” I have no idea.

The process for me is I tend to do these rather quick ink drawings, so that I can get models that have a pose that’s more energized and movement-based rather than a static sitting pose. Something in some of those poses invokes in me the beginning of a narrative, and that becomes the beginning of whatever story that happens, and I use that drawing to create more finished drawings. Usually it’s the female figure that sets the narrative, and then I draw the Minotaur in after the fact.

Clayton Porter: You said something earlier that I want to see if you can expand upon. You had mentioned you haven’t turned your back on contemporary art.

MB: Because so much of my work is so classically derived, people see it and automatically think I have no interest in contemporary art, that I’m only interested in the Renaissance, mythology, or Christian iconography. While I am interested in all of that, I see it all in terms of its reference to today, because you can’t help the fact that we’re living today, and we’re already influenced by the fact that we know so much more about psychology and the subconscious, art movements, communication, and we’re all plugged in with the world, we have Google, we can get information. All of that modifies how you understand any of this information. I guess what I want to say more than anything is that I don’t see anything irrelevant about using these ancient techniques or iconography to address something that is very contemporary. I think that makes it just as relevant, or more so, because you’re including a bigger array of history instead of saying, for instance, “I can only use Abstract Expressionism to say something about how we perceive the world, or how we understand color and light.” I think that that becomes a very formalistic concern, but it narrows the bandwidth.

For me, always the thing that seems to really resonate for me is when any artist—in any sort of field, whether it’s music or literature—can somehow take some references from history and incorporate them into something in contemporary life, and make you see it completely anew.

CP: Is there somebody who is working maybe in a genre or style that you appreciate that would catch us by surprise? And is there somebody that influences your work?

MB: For me, always the thing that seems to really resonate for me is when any artist—in any sort of field, whether it’s music or literature—can somehow take some references from history and incorporate them into something in contemporary life, and make you see it completely anew. To me, it’s brilliant. Think about something like the success of the play Hamilton. It’s like, what a boring character—but he’s not, he actually says something about current society, the issues we’re dealing with, but it’s all done with hip hop music, but it’s a classical character, and it’s talking about how to create a democracy, and what are the issues with forming a new nation. It entertains everyone today in a way that it couldn’t have done at any other time. I think that’s the most brilliant thing, and the same thing happened for me when I saw Angels in America. They took something that was about this cutting-edge, contemporary issue—AIDS—and created this beautiful, almost mythological story around it that made it so powerful. That’s when I go, “That’s art doing its job.” Suddenly you’ve said something beautifully about something that’s so contemporary, and it made me understand it in a way that made it seem bigger and more sublime than anything anyone writing a news story could ever say about it using facts and figures. And that’s our job. We can’t be history painters anymore like in the 18th century. Our job becomes narrowed to how the psyche interprets the world around us, and how you can then, as an individual, present that in a way that makes us so much bigger, so the world can say “Ah, that’s what it’s like to be human.” And you can’t teach that. But when you see it you just immediately recognize it, no matter what field.

I hate it when I go to shows, and I just go, “Man, I don’t know what this is.” Sometimes you just sort of feel sick; I don’t know if it’s me or if somebody just missed [the mark].

CP: Do you ever wish you could have another life or live in separate, parallel universes, doing something else?

MB: There is a lot of play with [media]. I do sculpture, drawings, paintings, I do a lot of things in terms of visual arts, and any one of those I could mine deeper. I could have spent a whole career just being a sculptor, and there are times I look at sculpture and I think, “God that would have been fun,” but there are times that I really like painting. I’m going to continue painting. In another way it kind of shifts over time when you realize that you aren’t a slave to the work, the work is a slave to you, in terms of where you’re growing or what’s happening for you. And as you evolve, the work that comes out of that is a reflection of who you are rather than you chasing your work. I think that’s where a lot of artists get it upside down. They start thinking “Okay, I’m doing this, so my life is about making this work,” but the work should be a byproduct of the work you’re doing to understand yourself and the world around you.

every time I’ve got stuck is when I chased the work, and I didn’t stay true to what was going on in me that created that work, and then that’s when I begin to realize, “Oh, I’ve gotta flip this equation, it’s the equation that’s wrong.”

CP: That’s a powerful statement. When do you feel like you came upon that revelation?

MB: I think it takes time to come to that realization, simply because when you’re young, you’re so busy trying to learn your craft: you’re focusing on improving your craft, seeing how you stand up to other people. Then you get caught up in the whole commercial aspect of fitting in a gallery, making sales, not making sales.

At a certain point there’s this epiphany, you know, that what makes sales happen or not is when you actually had something happen in yourself that got transferred to the work, and then everyone felt it in the work. So every time I’ve got stuck is when I chased the work, and I didn’t stay true to what was going on in me that created that work, and then that’s when I begin to realize, “Oh, I’ve gotta flip this equation, it’s the equation that’s wrong.” You see it in artists’ careers all the time, where you realize that at a certain point all they are doing are replications of themselves, they’re just sort of doing the same thing over and over and over, because that’s all that’s working.

CP: What happens, how or when do you know?

MB: That’s a really good question.

CP: Maybe it’s elusive.

MB: It is elusive, but there’s just this kind of a bone knowing. In a way, it’s sort of like looking around corners—you’re seeing around a corner and you know that it’s there and you’re coming on to it, and it’s true. That’s the only way I can describe it. It’s… I guess I don’t want to fall into the Santa Fe stereotype of woo-woo spirituality, you know, but it almost becomes like that. I used to have a poet friend in Denver who is a beat poet, and he used to tell me when I was just 19 years old, I’d be illustrating broadsides and stuff for him and he’d be amazed by how some of the images could have been so close to something he was writing or thinking at the time, and then he would always say, “You know, that’s the muse.” And I said, “Well, what are you talking about, the muse?” He says, “None of us are hip enough to know that, that’s something that’s happening that you’re just channeling, that’s not something you’re aware of.” I think that’s also part of it. At a certain point you’re acknowledging that you’re a vehicle for something that’s coming through. When you are so attuned to that, you can feel that happening, that you’re not inventing any of it, you didn’t conceive any of that, it’s just something that’s like an “aha” and that’s what you’re creating. It’s just this flowing aha, and when that happens, that’s just ecstasy. Damn if I know how you stay there or how you get there [laughs], but I think the more that you do that, the more you sort of sense that coming along and you sort of line yourself up for that to happen.

LT: Are there things that you think about or practice to make yourself more receptive and more in tune with that “aha,” and allowing that to happen?

MB: I think we all have this issue as artists: what is our process? How do you get to that space where something starts to happen? Some people need to just start throwing paint on a canvas or whatever. For me, it’s always been to sit down and start drawing from life. And as I start drawing, I sort of drop down into something, and I start seeing something. I start moving things around and then it will kick off from there, but that’s just my process.

A lot of times I will just start looking through Pinterest or something and see images and start tracing. The internet is glorious, you can just get lost in this rabbit hole of endless imagery. You find something and you click on that, and it opens up a whole other category, and before you know it you’ve just started realizing, “I’m fascinated by this,” and once you realize you’re fascinated, then you’ve got a hook. Whatever that is, it’s like something wants to be expressed, you’re a vehicle for that to be expressed. Once you find that hook, it starts to pull that out of you, and you start to let that express itself.