Tansey Contemporary, Santa Fe

August 4 – 25, 2017

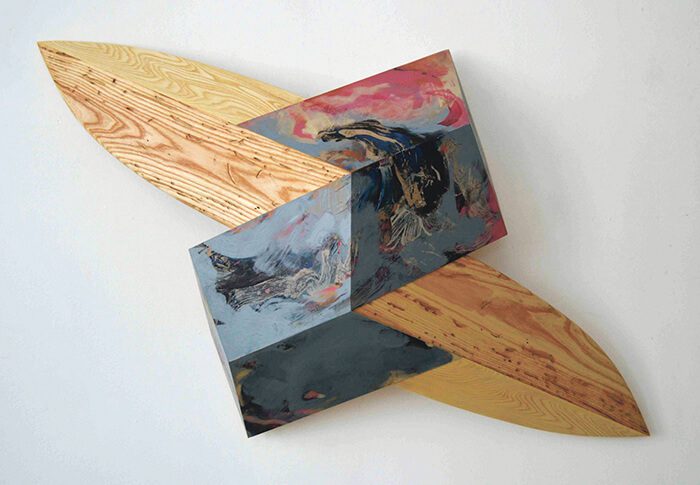

In her solo exhibition of geometric wall sculptures, Melinda Rosenberg’s lines are not always her own. The Columbus, Ohio, artist’s work is a collaboration with designers and craftsmen of the past. She excises bits and pieces of weathered furniture and other decaying design objects, folding their forms so gracefully into her sculptures that they tip into a new visual vocabulary.

Puzzling over the origins of Rosenberg’s materials is an impulse happily indulged. Bits of canoe, love seat, tree branch, and other found wood meet along crisp seams, creating abstract forms that the artist stains with bright aniline dyes. A peek behind several of the convex works reveals neat wooden armatures. This is a game of mental and physical origami, executed as though these unforgiving materials were as pliable as paper.

Rosenberg draws inspiration from the sukiya style of Japanese architecture, used to design structures for traditional tea ceremonies. Some of the works in the exhibition, particularly those from the artist’s X series, would make perfect roofs for futuristic, dollhouse-sized tea rooms. For this exhibition, however, Rosenberg tilts her attention away from architecture towards an age-old battle between fine art and craft.

The artist adds swirling fields of pigment to some of the works, turning them into many-planed canvases for abstract paintings. “All of the history and weight of mark-making is at play, but countered with the self consciousness of seeing around the painting to the back,” Rosenberg postulates in the press materials. “The physicality of wood counters the apparent depth and atmosphere of paint.”

The aesthetic choice is aimed at conjuring tension between sculpture’s physicality and painting’s “illusionism,” but it’s a lopsided fight. Rosenberg’s abstract paintings read like weak parodies of the genre, and she sands down her brushstrokes, rendering them flat and lifeless. Next to the dazzling craftsmanship of the sculptures, the paintings feel like parasites that barely hold up their end of the compositional conversation.

Found and Made engages with other strains of art history more naturally, opening up richer territory for Rosenberg to explore. Minimalism and postminimalism are clear touchpoints, but the artist has the opportunity to venture much farther.

On a narrow section of wall just below the gallery’s vigas hangs one of the exhibition’s crowning achievements, a sculpture made from croquet mallets and swooping sections of wood amputated from an unidentified piece of furniture (perhaps they’re the legs of an ornate table or the sides of a headboard). They blend seamlessly to form a propeller, with the rainbow mallets projecting from the ends.

Here is a potential entry point to a surrealism-inspired series. If Rosenberg strayed a bit farther from her formal geometries, she could don the lab coat of a crafty Dr. Frankenstein, stitching together functional objects to surprising effect. The propeller possesses the delightfully perverse logic of a Méret Oppenheim: fur keeps your tea warm, and a spinning mallet could perhaps up your croquet game.

Of course, the work also resides at the fertile crossroads of craft traditions. Rosenberg’s artful repurposing of humble materials recalls the exhibition No Idle Hands: The Myths and Meanings of Tramp Art, on view at the Museum of International Folk Art through September 16. The exhibition is a sweeping survey of an intricate woodworking style that originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Tramp art practitioners notched and layered old cigar boxes and fruit crates to form a great variety of domestic objects. Jewelry boxes, shelving, ornamental wall hangings, and musical instruments are dressed up as treasures, using the cheapest of woods.

Rosenberg’s clean lines stand far apart from the universe of tramp art, but her philosophy of recycling and obsession with wood grain aligns with the movement. Like the tramp artists, she elegantly balances the precious and the worthless, the mundane and the remarkable. Modern and contemporary artists have already challenged the history of painting ad nauseam. Rosenberg has the skills to strike out for less trodden frontiers.