July 7 – September 2, 2017

Peters Projects, Santa Fe

Upon entering Kent Monkman’s solo exhibition, resist the temptation to revel in the raucous party raging across monumental canvases in the show’s main room, and head straight for the smaller alcove in the back. In this makeshift cabin—complete with faux wallpaper bearing queer erotica infused with Wild West kitsch—hides the artist’s alter ego, Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle. That’s “Mischief Cher Egotistical,” to you.

The two-spirit, time traveling, gender-bending trickster stars in a series of photographs that Monkman made with Chris Chapman, titled Fate is a Cruel Mistress. In these diminutive giclée prints on paper, Miss Chief plays five of the Bible’s wickedest women. Among them is a bare-chested Jezebel luring a priest to Paganism, Salome cradling John the Baptist’s head on a silver platter, and Potiphar’s Wife seducing her husband in vain.

Adding new layers of history and meaning, the images are set in 1860’s Canada during the process of Confederation. Several of the Biblical characters become Indigenous women, caught in intimate conflict with stiff-collared white men as their lands are forcibly unified under a new flag. Delilah, for example, sits in a tipi with a drowsy, half-naked Samson draped across her lap. She stares at the viewer with a mixture of fear and resolve as she prepares to snip another lock of his hair. Undercurrents of sexual violence and vicious colonial power dynamics bring an old tale crackling back to life.

The series represents Monkman’s modus operandi, spelled out through relatively simple allegories. The First Nations artist, who is of Cree descent, sends Miss Chief tearing like a meteor through histories of the Americas. Long-dominant colonial narratives explode with surprising speed when you place a queer, Indigenous person in the role of the protagonist. The same goes for older legends that formed the ideological foundations of colonialism, such as Bible stories and classical myths.

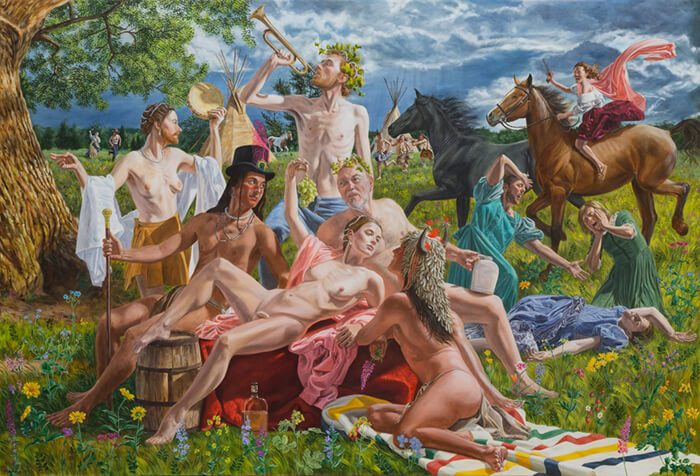

Only after thoroughly examining Fate is a Cruel Mistress should you return to the exhibition’s main body of work. The Rendezvous series is set on the American frontier in the early 19th century, when Indigenous peoples, trappers and traders gathered for unruly soirees to celebrate winter’s end. “This final chapter of freedom for the Indigenous nations was a brief golden age in terms of the balance between the settler and Indigenous populations,” the show’s press release posits.

Monkman draws primary inspiration from the work of 19th century American artist Alfred Jacob Miller, who attended one such rendezvous on a Western excursion in 1837. Miller’s drawings and paintings of the proceedings mimic the gauzy aesthetic of French Romanticism. Monkman’s acrylic paintings on canvas make fleeting reference to this style, leaning more heavily on the legacies of history painting and social realism to pull tangles of figures into focus.

Miss Chief is replaced here by a large cast of queer and gender-nonconforming characters who frolic about in frontier garb and their birthday suits. They drink, dance, fight, wed, and give birth, reenacting actual accounts of Miller’s rendezvous or taking the roles of the Virgin Mary, the Three Fates, Cain and Abel and other famous figures.

Monkman, who identifies as queer and two-spirit, has stated that the series explores the societal frontier of transgenderism within contemporary American society. Occupying the fleeting periphery, these figures revel in freedom of expression in spite of forbidding powers that approach from the East. The creeping threat of Manifest Destiny and the present rollback of transgender rights make for clear analogues in this context.

These are paintings as Hollywood summer blockbusters, capturing moments of unbridled emotion but also teetering under the weight of their own scale. Monkman masterfully captures the wide shot of the party, slinging epic iconography and snappy visual wisecracks with equal force. Unfortunately, the action never lets up enough to bring us down to eye level. Too often, Monkman allows the characters to get lost in their legends, careening towards the same one-dimensional storytelling as his source material.

There’s one name missing from the guest list that could set things right: Miss Chief. In Monkman’s previous exhibitions of large paintings, the character popped up occasionally to act as a focal point and guide, simultaneously embodying figures from each period and a contemporary viewpoint. In the pared down compositions of Fate is a Cruel Mistress, Miss Chief does just that. Without clear protagonists, The Rendezvous risks reducing its characters to a sweaty, anonymous tangle. It might be a good party, but it’s conceptually slurred.