Kellie Bornhoft’s work collaborates with the landscape, presenting both the long view of geologic time and intimate perspectives in poetry and gesture.

On September 9, 2020, Kellie Bornhoft awoke to a dark sky, the sun a mere orb of red-orange. Smoke from wildfires across the state of California and the Pacific Northwest converged with the marine layer off the coast and blanketed the Bay Area with a thick, nearly impenetrable smog. It became known as “the day the sky turned orange,” and like many, Bornhoft went outside and documented the apocalyptic sky.¹

“It was unreal,” Bornhoft relates to me over a recent Zoom call. “The air was actually not that bad that day because the smoke was all stuck above the marine layer, which is what gave it that effect. So I went outside that day and was able to record video.” Bornhoft’s video Sun Breathing (2020) is the result, a grid of nine floating, tangerine-colored suns, variably bouncing up and down with a slight shake as the artist coughs. “What was so interesting to see at the time was how fascinating the sun was—you could stare directly at it, and it was this kind of toxic orange—so this video was a reaction to being able to stare directly at the sun,” she says. Holding the camera against her chest, Bornhoft, who has asthma, recorded about thirty minutes of footage, looking up at the sun while attempting to breathe deeply, exploring the relationship between her “fascination of looking at the sun but also the impact that [the smoke] had on my body, which was changing my breath,” rendering her unable to contain her cough. Bornhoft then condensed and stacked the footage into a grid to create a two-minute looped video, the suns becoming what the artist likens a “chorus.”

Watching Sun Breathing progress, I am struck by a chord of melancholia, a kind of despondent ache for the future, for the damage already done. The shaky suns, floating tenuously in their far-awayness, seem to extend only the most fragile of lifelines to an ailing planet. The apocalyptic orange sky over San Francisco was an event seared into collective memory during a year when everything felt like it was falling apart and when the future loomed with uncertainty. Bornhoft then asked me if I had lost power during the deadly deep freeze in February 2021 in Texas. I was lucky in that I’d only suffered frozen pipes but no power outages, but I am still struck by the fragility of the systems we rely upon, built upon foundations of avarice. “There’s this kind of fire and ice of the last year,” she says ruefully. “I think those moments are really important because we get caught up in the status quo,” she continues. “There’s science and there’s data telling us that the planet is warming and we are moving towards disaster but it’s not until we have those memorable experiences that it really saturates our psyche.”

Watching Sun Breathing progress, I am struck by a chord of melancholia, a kind of despondent ache for the future, for the damage already done. The shaky suns, floating tenuously in their far-awayness, seem to extend only the most fragile of lifelines to an ailing planet.

Bornhoft’s grandmother always keeps a box of ice skates at her house near Kansas City, Missouri, for ice-skating on a nearby pond. The pond, however, has never frozen over during Bornhoft’s lifetime—and yet the box of ice skates are kept, just in case. “The concept of generational memory is really important to the discourse of how we understand climate change, because climate change is so slow,” she says. “My grandmother, who is almost ninety, may not recognize it, but she is able to remember a different ecosystem that she lived in, with different kinds of weather patterns that are unfamiliar to me. But without the box of ice skates [the difference] is not measurable, noticeable, or tangible.”

In Bornhoft’s book, Shifting Landscapes Static Bounds, published as part of her MFA thesis work at Ohio State University in 2019, she references Timothy Morton’s concept of the “hyperobject,” something that is so vast in temporal and spatial scale as to be incomprehensible to traditional ways of human understanding—climate change being the most significant example. “The issue is not the distribution of information, it is the overwhelming affect of such information,” she writes:

The sickness of our environment is so sublime that we disengage from the facts to cope. News articles and data charts, if taken in, petrify. Headlines float upon the surface of my understanding but in their enormity they fail to saturate my being. This year California has had the worst fires in history. While some people may understand the depths of what another couple degrees Celsius warmer planet looks like, I find it hard to grasp.²

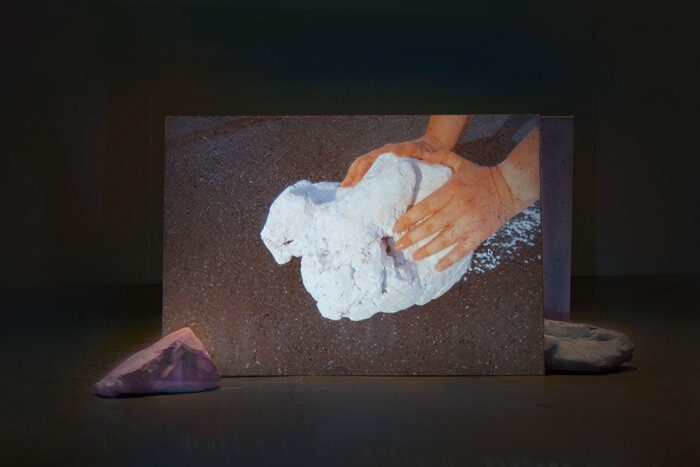

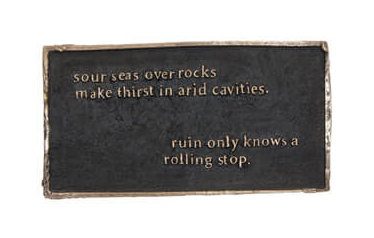

Bornhoft’s work collaborates with landscapes in the Southwest, as well as the West Coast, Midwest, and beyond, presenting both the long view—of geologic time, histories of colonization and resource extraction—and intimate perspectives in poetry and gesture. In developing the project Shifting Landscapes Static Bounds, Bornhoft visited national park sites in Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming, leaving behind bronze plaques bearing stanzas of her poetry and taking stones in return. In Bornhoft’s drawing series Burnishings (2018-present), she uses forest-fire generated charcoal to take rubbings of the bark of native trees on public lands across the United States. In her two-channel video installation Boundless Sediments (2020), we see lines of poetry stamped in ocean sand and washed away by the waves, while Bornhoft alternately pounds a large rock of hardened plaster to dust or pushes it across a paved parking lot, leaving behind a marked trail as the stone slowly diminishes. “I’m really interested in how the materiality of the earth is transforming because of our human presence on it, and the damage that we are doing,” Bornhoft says. “Two things that I try to approach in my work are the narrative of our relationship to the earth and its changing circumstances but also getting that physicality and tangibility is important to me.”

Bornhoft’s practice straddles sculpture, installation, video, and performance, but post-grad school, and as COVID closed shops and studios, she has been drawn to video, partly out of necessity but also for its narrative potential. “I think right now I have an itch to make more physical objects since I’ve been working primarily on video for the last couple of years. But I see the two really tied together: undulating, going in and out, woven together,” she says. The day the shelter-in-place announcement was made for Santa Clara County, California, Bornhoft was installing Boundless Sediments at a gallery in San Jose. The installation remains shuttered, just as she left it, likely to finally open in the fall.

Bornhoft’s latest video, still in progress and as yet untitled, juxtaposes the landscape—bodies of water, faults, and fissures—with her pregnant body. It was during that unprecedented fire season last year, with the sky cloaked in a blanket of smoke, when she learned she was pregnant. “A lot of [the rhetoric surrounding] environmentalism is ‘for the future generation’ or ‘for our children’s children’ but there [needs to be] an accountability for where we are at right now,” she says. “There’s something so heteronormative about that narrative, that procreation is the goal. But really it shouldn’t be so human-centric, it should also be for the plants, for the flora and fauna. It doesn’t have to centralize a human legacy.” In her work, Bornhoft draws attention to the tangible and material changes in our environment, so we can understand our impact while locating our relationship to our ever-shifting and always-changing planet. Our approach should be more grounded in “sensitivity and sincerity” to the world around us, she says. Perhaps, in that way, we can learn to shape the change, to draw the anthropocene era away from the apocalyptic.