Junk Drawer is an inclusive queer techno dance party in Denver featuring installations by local artists who bring together social-justice politics and joy.

DENVER—Junk Drawer, as founders Justin Najjar-Keith, Jeff Page, and Aleks Rodriguez often repeat, is more than a party. It’s a party as art, art as a party. It’s an act of social dynamic-shifting community service. It’s an education on the BIPOC roots of the techno music dance scene. It gives people an outlet when they, like Rodriguez, “need some faggotry [and] to twirl.” And it’s beyond gender in the profound intimacies it generates.

I entered Najjar-Keith and Page’s home as they put their toddler to bed, leaning into blissful domestic solace after the crowded, glimmering cacophony of the Junk Drawer celebration we attended a few nights before in early May 2023. Their living room provided the same setting where they crafted decorations with friends in Junk Drawer’s early, sans-toddler times. They also let their first hired DJs sleep in their guest room, loaned them their car, and fed them home-cooked meals.

Soon after Najjar-Keith and Page threw their inaugural Junk Drawer event, Rodriguez met them at a 2018 Honcho Campout, a queer electronic music festival based in Pennsylvania. Serendipitously camping next to Najjar-Keith and Page, the trio exuded a shared passion for bringing a dynamic—energetic yet vulnerable and supportive—queer party to Denver. Ever since, Junk Drawer, with its mission to yield the variety and playfulness embedded in the innuendo of its name, has filled a queer void in Denver’s underground scene.

Junk Drawer, which emphasizes social justice, engages people who seek visibility, healing, and celebration. Moreover, tired of the pervasive male-dominated gay clubs, Junk Drawer dreamt of welcoming trans, women, and femme-presenting bodies. Although they’ve been a historically formative presence in the queer techno underground, these individuals are often relegated to the sidelines, feeling unsafe or uncomfortable in such environments.

Print and digital media emphasizing consent, acceptance, and joy evidence Junk Drawer’s open ears to the individuals they seek to include. Partnering with Liminal Spacers, a self-described “dance space harm reduction project,” Junk Drawer parties also provide information about police-alternative community services alongside free fentanyl tests and Narcan, which can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose.

The House of Flora, a Portland- and Denver-based kiki house (drag queen subculture) that carries on the late 1970s tradition of BIPOC-instituted ballroom “vogueing”—made mainstream through the 1990 documentary Paris is Burning—performed at a 2019 Junk Drawer event at Denver’s RedLine Contemporary Art Center. Subsequently, members are always put on the guest list, electrifying the dance floor whenever they attend with choreography and costumes that, to borrow kiki slang, “will make you gag.”

While music and vogueing confer performance art to Junk Drawer, the events also feature art installations. After Najjar-Keith and Page became parents, which halted the living-room craft sessions, they hired Haley Dixon as their first local artist. Since then, artists including Justin Decou, Andi Todaro, Frankie Toan, Club Flower, and Alicia Ordal have furnished Junk Drawer sets.

Charles Bloom designs the highly anticipated fliers that party-goers save as collector’s items. Bloom’s party announcements, which typically feature a free-floating gnarled hand adorned with witch fingers (plastic, pointy-finger attachments found at costume outlet stores), emblematize the spooky regalia offered on a serving platter at one memorable Junk Drawer night.

Although Page, who organizes the optic and online presence of the parties, is the only professional visual artist among his collaborators, Junk Drawer provides a pleasurable creative outlet for all. An architect by trade, Najjar-Keith, who coordinates Junk Drawer’s finances, revels in organizing and decorating spaces unhampered by his industry’s strict codes and policies. Rodriguez, who has a long history working as a nightlife and festival coordinator (including with Honcho campouts and the Denver club Beta), is the “star host” and promoter.

The prevailing syntax of Junk Drawer also derives from Rodriguez. With “CUNTY” tattooed on his thigh (identified as his “birthmark”), Rodriguez uses and builds on kiki elocution. When asked what distinguishes Junk Drawer raves, Rodriguez responded with “bitchy grat(t)itude,” which means allowing people to tell their stories and celebrate diversity without leaving their gossipy attitude at coat check.

While Rodriguez brings the grat(t)itude, Page cultivates a space where art and activism converge. Considering his artistic preoccupation with how social-political discourses intersect with his personal life, he feels like an outsider in an art world that is verbally enthusiastic—but apathetic in practice—about social justice.

Similar to Najjar-Keith, Page feels more liberated in his Junk Drawer-related art-making. Besides, while a gallery restricts your interaction with still images in a hushed setting, a rave lends itself to ecstatic, unpredictable, immersive experiences co-created with perspiring multitudes dressed like Leigh Bowery reincarnations.

As its own art practice, Junk Drawer is a work in progress with an ethos that necessarily shifts as the dangers that impede upon the community shift. In this moment of anti-trans and anti-drag queen legislation—with nationwide courts debating the suitability of public drag shows and the ethical responsibility to provide young people with gender-affirming health care—Junk Drawer knows that public displays of authentic queer joy serve as a powerful prophylactic against menacing authorities seeking their violent eradication.

With this in mind, Junk Drawer’s next offering, an after-hours Denver Pride bash, is scheduled for Saturday, June 24, 2023, at a location to be revealed to ticket-holders on the day of the event. (Tickets are available through Eventbrite.)

While saying my goodbyes to the Junk Drawer masterminds, Rodriguez offered a final slogan: “Come correct,” which I misheard as, “Come corrupt.”

“Yes!” Rodriguez adapted my distortion: “Come corrupted by heteronormative society.”

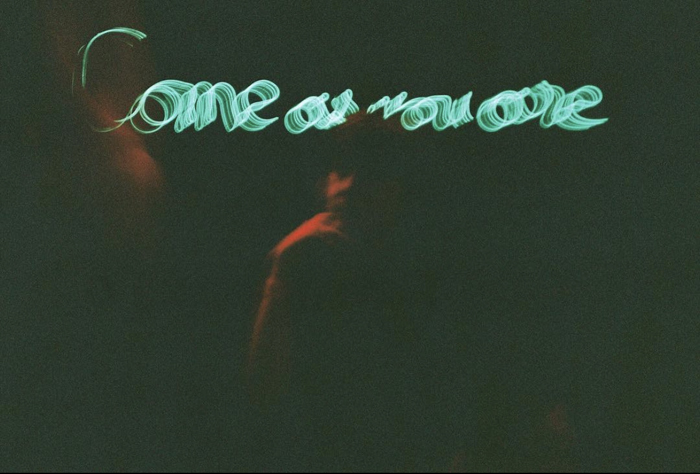

“We used to have a neon sign that said, ‘Come As You Are,’” Page observed.

“Oh? What happened to it?”

“We left it out in the rain, and I think a cat peed on it,” Najjar-Keith informed me.

Ending the night with laughter, I reflected on the perfection of the disappearing sign, one no longer needed to advertise acceptance and inclusion where such expectations reign.