June 2 – November 10, 2019

Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

Looking at a torn vagina in Judy Chicago’s Creation of the World: Needlepoint 1 (1985), I remember watching my ex-partner give birth to both of our boys at home. She had a tear that had to be sewn. I watched, and that is the extent of my experience with childbirth. I know, however, that men—which I’ll define as cis-gendered, penis-possessing humans—have a lot of opinions about what goes in and out of vaginas… and what stays. Lately, the more patriarchal among us have had too much power determining these conditions. They are fixated, of course, on abortion, but their anxiety is congruous with men’s fear of women’s ability to make life and therefore society. If men can’t ultimately control life, they will control the bodies that create it. Anne McClintock writes that baptism is an expression of this fear, an attempt to take birth from women, ostensibly purifying earthy (soiled) female birth in God’s amniotic fluid (holy water), while a male midwife (the priest) takes all the credit. In short, baptism mystifies birth, erases women’s labor, and positions men as great makers of society. Materially, it conceals the damage pregnancy does to a woman’s body, the violence of abstinence-only ideologies, and, in New Mexico, a higher-than-average mortality rate for women in delivery.

For me, Creation of the World: Needlepoint 1 contains these experiences, histories, and power dynamics. It’s not that different from other depictions of creation or torn vaginas in the exhibition of Chicago’s work, Birth Project, at the Harwood Museum of Art. However, the exhibition relies more broadly on the social relations that make it possible, more than the objects. In the needlepoints, quilts, and crochets, it also explicitly contains genealogies of women who shared their birth stories, modeled for Chicago, and performed the actual labor of making the artworks based on Chicago’s designs. Each of them is named in the accompanying labels. At the same time, this genealogy includes a number of very present absences.

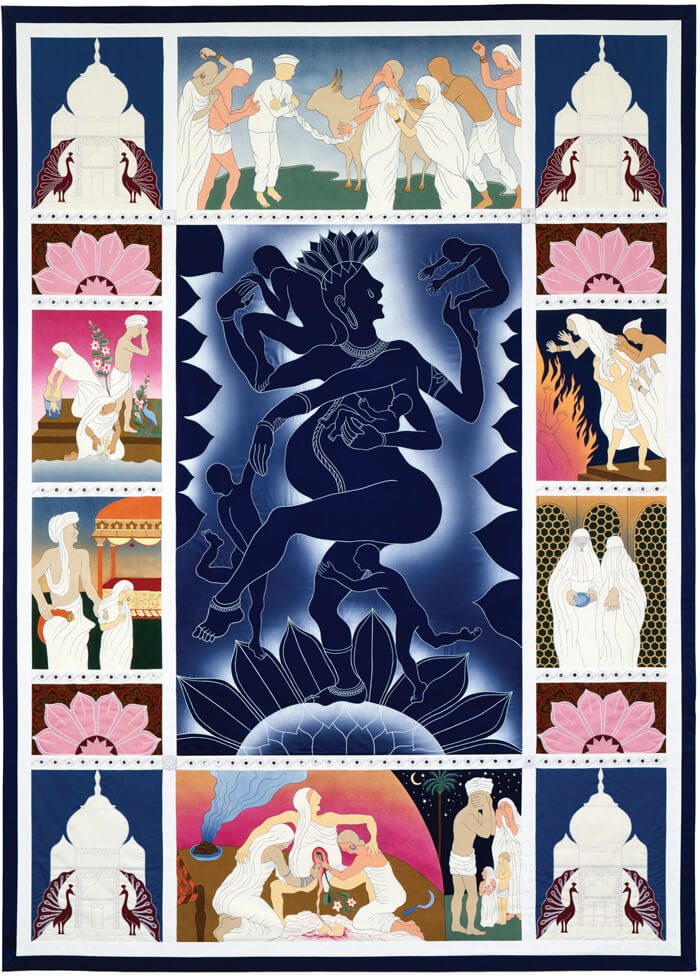

Birth Project demonstrates structural and ideological shortcomings in Chicago’s work by representing an essentialized womanhood through a depiction of childbirth that relies on appropriated mythologies. Works like Myth Quilt 2 (1984) take creation mythologies out of context and flatten them, while works like Mother India (1985) cultivate white feminist fantasies about saving women of color in so-called “third world” countries. In the former, we see the assimilation of world cultures into one; in the latter, we see justification for imperial occupation. (I was in high school during Desert Storm; I certainly remember “for the women” being a common refrain during the occupation of Iraq.)

Some viewers might use the word “dated” to describe Chicago’s work, but that would ignore its very contemporary presence in New Mexico, in the Harwood Museum, in Taos. How do anglicized depictions of creation resonate in a resort town built around a Pueblo? How do “universal” themes of womanhood justify the ongoing occupation of Native land while Native women disappear at a rate higher than any other ethnic group? Where is womanhood for women who don’t have children, or vaginas?

I don’t know the experience of a mother who has given birth, nor of women who have suffered through a patriarchal system because of their ability to do so. Perhaps they find validation in Chicago’s work; perhaps they can show her work to their partners and say, “This is how I feel.” We can also recognize that representing white women as (torn) vessels for humanity also perpetuates racialized and patriarchal hierarchies. I can look at the needlepoint and feel something for the mother of my children, but I can still look over my shoulders to viewers who accept the view that women exist through what they can produce rather than whom they chose to be and whom they choose to love.