Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO

February 2-August 18, 2019

In a video interview installed in Returning the Gaze, painter Jordan Casteel says her encounters with portraiture in museums and galleries have typically involved “dead white people” in staid poses. Her large-scale oils on canvas subvert that trope in a number of ways, and with a verisimilitude that is crucial in these still-racially divided times. Casteel recreates scenes from her everyday life in Harlem, New York, with themes encompassing brotherhood, visibility, and self-pride among her friends and community members, many of them African Americans or immigrants. Above all, Casteel prioritizes universal messages of acceptance, love, and human kindness.

Even though she’s just on the cusp of thirty, Casteel steadily produces work that embraces these lofty goals, and it has helped her rise to the forefront of American portrait artists. The Denver Art Museum is the site of her first solo museum exhibition, spanning 2014 to 2018 and including about thirty paintings. Casteel grew up in Denver and left after high school to attend college in Georgia, get her MFA in painting from Yale, and then to settle in Harlem. A number of Casteel’s earlier paintings reference Denver friends and family.

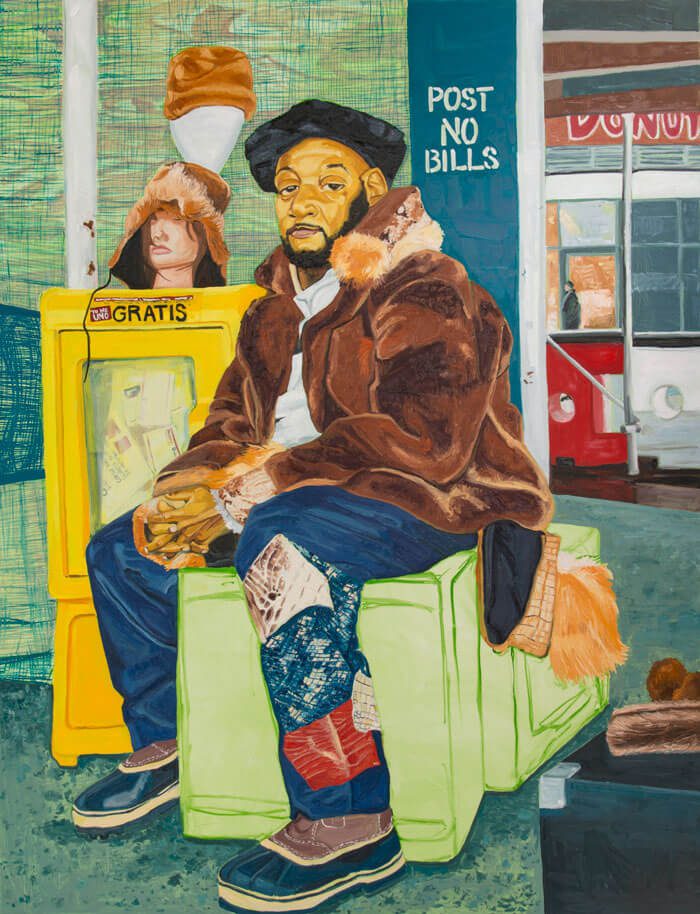

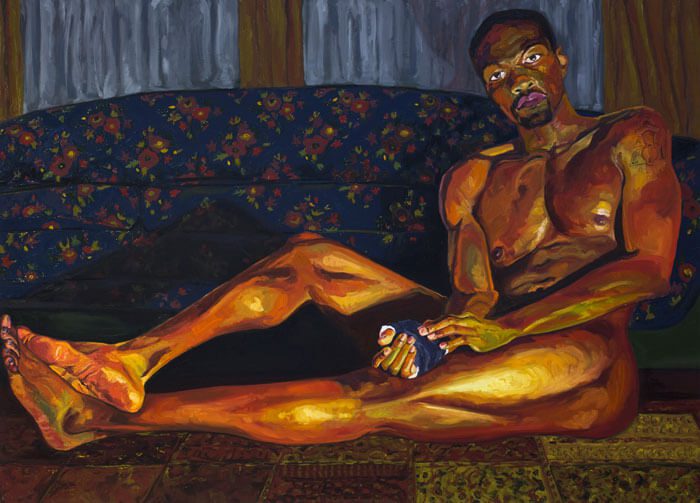

The gestural, boldly colored paintings stand on their own, and through them, Casteel explores the dynamic between the artist and her human subjects. Returning the Gaze is a fitting title because of its two-sided implications. Not only are we wondering why Casteel chose a particular sitter and how she studied physical form, light, setting, and color to inform the painting; but also, we want to know the thoughts running through the sitter’s head, his or her attitude about achieving this kind of posterity on canvas. In almost all the works, the sitter or group of sitters meets the artist’s gaze with calm and confidence—a testament to the rapport and empathy Casteel established. Several of the portraits are based on photographs she took while walking around Harlem. Two examples are the almost-eight-foot-tall Fatima (2018), depicting a Muslim woman contentedly posing in front of her food truck, and the six-foot-tall Charles (2016), in which we infer that the quietly smiling sitter, wearing a fur hat and coat, sells similar pelts on the street. In both cases, Casteel demonstrates a keen ability to capture an ordinary moment with selective but purposeful detail. In the process, the artist venerates subjects and settings that often are overlooked. Against expectations of artistic distance, Casteel instead has us believing in the unwavering, even welcoming, gazes exchanged between artist and subjects and, by extension, the paintings foster our own engagement as viewers. Casteel’s series of nude portraits of African American men, painted earlier in her career, are fascinating in their bold application of green, blue, and orange paint for flesh. They affirm, even celebrate, light’s effect on skin tones, from coolness to warmth and in between.

The exhibition is arguably at its strongest in the “Brotherhood” section, where the scenes include two black men or more, related or not, who project a comfort level with their black identity that viewers don’t often get to glimpse in an art museum. Plus, the figures convey an obvious symbiosis flowing between them. Particularly telling are the works in which Casteel strives for symmetry and balance. For instance, Hamilton Cousins (2015) positions the two men on a sofa, their legs in a similar relaxed position. One cousin lays his left hand over his right; the other lays his right hand over his left.

Casteel remarked in a media preview for the show that she has become friends with many of her subjects. It’s not surprising, as it reflects her humane approach, her respect for others’ narratives, and her sincere dedication to capturing the less-visible segments of society.