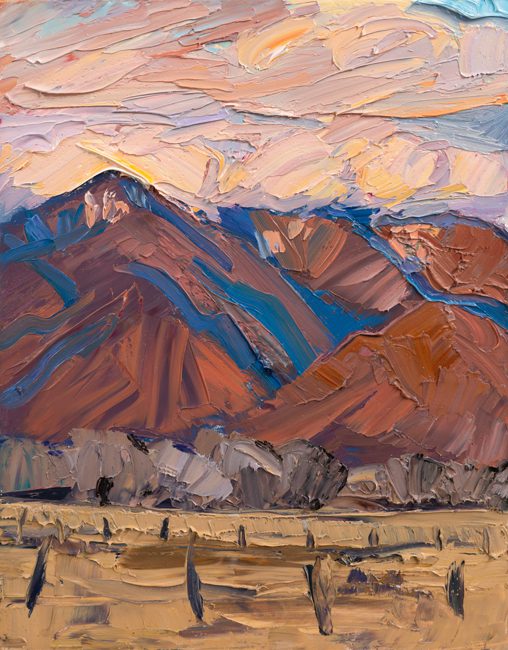

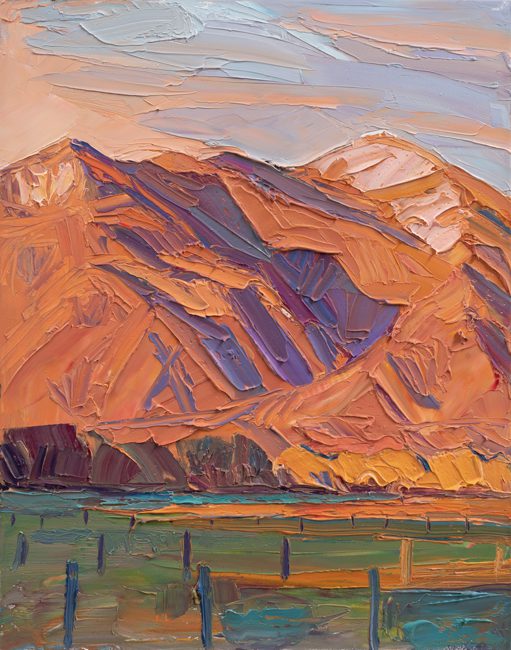

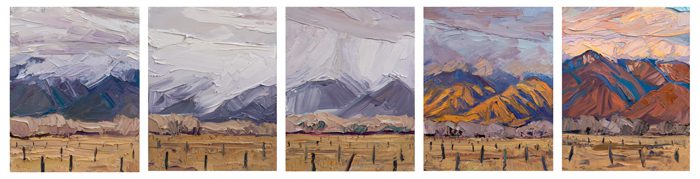

Jivan Lee’s series 10,000 Mountains represented a fundamental shift for the painter from chasing the light to deep meditations on place that revealed the miraculous through the mundane.

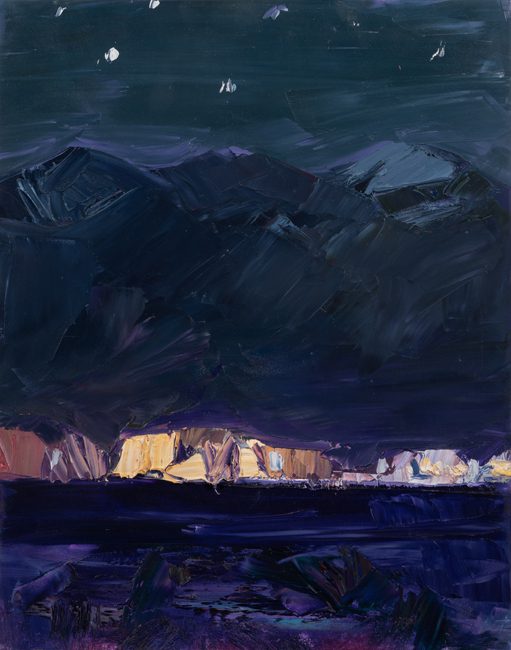

An hour after sunset on March 8, 2022, Taos artist Jivan Lee placed the last brush stroke in the field on a series of more than 360 paintings of Taos Mountain. He hadn’t intended to complete his series that night. As the cold settled over the field where he had stood for so many hours, his hands cramped around his brushes. Sunset faded into the dark of night, and a coyote howled in the distance. He gave into discomfort. “What I got in return was awe and peace,” he says.

Lee concluded the series in much the same way he’d begun more than fifteen months previously—in surrender to a place so familiar and yet still so unknown to him. The landscape painter accidentally launched what became the 10,000 Mountains series in January 2021. The long-form meditation considers a single subject, Taos Mountain, within the bounds of eleven-by-fourteen-inch panels. Over the course of five seasons, with seventy-two paintings representing each season, he tapped into the mundane and the miraculous.

“The elegant egotistical story was I had a clear vision for 10,000 Mountains,” Lee says. “Honestly, I found out that I was going to be getting a divorce from my wife, and it took the wind out of my sails for doing large-scale work.”

Feeling unmoored, Lee sought solace in a field near his home where he’d previously found personal grounding. He started to paint. Just for himself. Just to see what happened.

One painting turned into three. Soon there were twenty. Then a season’s worth of seventy-two panels. Then hundreds of paintings that, in their repetition and progression, looked as though someone was scrolling a smartphone’s camera roll. It grew into the largest project he’s completed in his career.

His goal isn’t and never has been to reach 10,000 paintings. Instead, he borrowed the number for the title from Taoism as a suggestion of the infinite and intangible. It also harkens Malcolm Gladwell’s notion that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master a skill. However, he says approaching mastery of this subject is farcical. “I could paint 10,000 paintings, and I’d never know this mountain in more than a drop of its geologic time.”

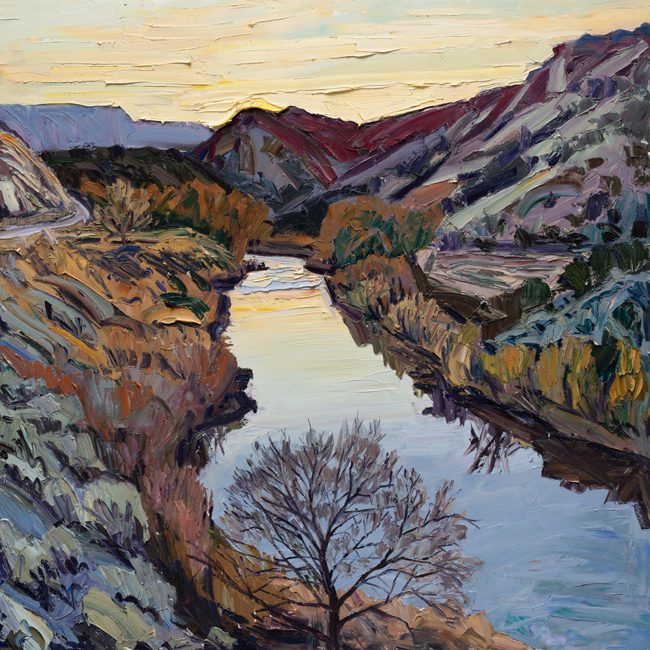

Hailing from Woodstock, New York, and with an academic painting career under his belt from Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, the painter says he needed several years of “stalking the sunrise and sunset” to develop a vocabulary with the West.

The series 10,000 Mountains represented a fundamental shift in his approach from pursuing subjects in their best lights to valuing a subject in all its literal and figurative lights—even on snowy, rainy, and wildfire-smoke days. He painted in the height of summer during midday, when he felt like he was standing in the sun’s spotlight, and in the depths of winter when he could barely make out the mountain’s form through the fog.

He sketched the outline of Taos Mountain each session, introducing human fallibility into its form, and completed each painting in the studio. Over a season, he lined the floor of his auto-garage-turned-studio with paintings. Often, he couldn’t take stock of the season’s progression until it was complete.

He painted to the point of “total, dead boredom… it felt like when you repeat a word until it loses meaning,” he says. “Then you’re questioning what words are at all, then, ‘What is language? Who am I? What is it to be alive at all?’”

By tapping into the mundane, he unearthed its worth. “It became about the slow, about the value of doing something again and again. Most of life is not the initial burst, but the moments in between,” he says.

Like social media posts, these old-fashioned paintings captured the mountain in neat little squares. However, by presenting it in an unfiltered light, he revealed a relationship between landscape and painter. “The mountain is never the same mountain, and we are never the same as we meet it day after day,” he wrote in a 2021 essay.

Tracking exterior weather across the mountain’s face created an internal shift. Lee found something miraculous in the laborious “chopping-wood and carrying-water” routinization of his practice. “In this repetition is a surrender to just meeting nature as it is, and as I am, on any given day amidst the bigger story of time and change,” he wrote in a 2021 essay.

His 2021 solo exhibition at LewAllen Galleries hung the first season of 10,000 Mountains / Winter. He has three exhibitions planned for this summer of 2022: Pretty Pictures at LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe from July 22 to August 22, The Infinite Landscape at Couse-Sharp Historic Site in Taos from June through September, and a two-person show with Lynn Boggess at William Havu Gallery in Denver, scheduled from June 24 through August 21. His Denver and Taos shows will exhibit selections from 10,000 Mountains. The other show will focus on his large-scale works, including meditations on two other special locations on the Rio Grande.

He’s still searching for a way to exhibit the project in its entirety. He’s at peace with the unknown.