Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Research Center Conversation

Tuesday, November 28, 6 – 7 pm

Faye Gleisser, the Georgia O’Keeffe Research Center’s current postdoctoral fellow (September 1-December 31), finds inspiration in the work of scholars and artists who disrupt linear historical periods. Fred Wilson is particularly influential. Gaining renown in the early nineties, Wilson juxtaposed seemingly incongruous objects (silver repoussé with slave shackles, for instance) for his groundbreaking exhibition, Mining the Museum (1992). Similarly, Gleisser draws out relationships between atypical pairings of artists in her forthcoming book, Guerrilla Tactics: Art, Performance, and the Politics of Resourcefulness, 1967-1987. From these associations, fresh dialogues emerge around an era when militancy and revolution gave way to new aesthetic practices, a broader “cultural romanticization of deviance,” and heightened levels of policing public space.

Alicia Inez Guzmán: It seems like a big task, but can you define some of the “guerrilla tactics” of the long seventies that underpin your thinking on the subject and your book project on the whole?

Faye Gleisser: Generally speaking, guerrilla tactics have existed for centuries and broadly define rogue fighters’ low-tech counter-resistance strategies of infiltrating and sabotaging military actions through psychological interference and armed assault. Beginning in the 1960s, however, an unprecedented type of urban guerrilla tactics emerged in the U.S., made possible by the newly available technologies of broadcast television, Xerox, and Portapak video. Amidst the media’s coverage of counter-resistance in Vietnam, Africa, and Latin America, militant encounter groups formed and adapted tactics that had been promoted by Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, and Mao Zedong. They sought to expose and challenge the colonialist, racist logics structuring American politics and society, including: the Black Panther Party’s strategic demonstration at the Sacramento State Capital, protesting the Mulford Act in 1967; the emergence of the Guerrilla Television movement, which provided alternative footage, for example, of the 1972 Republican and Democratic National Conventions; and the Symbionese Liberation Army’s political kidnapping of Patty Hearst in 1974, which subsequently led to the San Francisco Chronicle being taken hostage as well. My book argues that these differently motivated but interconnected events are part of the wider cultural domestication of militancy that occurred during the ‘long’ 1970s—a period framed by the murder of Guevara in 1967, which marked the emergent visual mythology of a “heroic guerrilla,” and the eventual coining of “guerrilla marketing” as a business strategy in 1984.

What was performance art’s relationship to those tactics? Are we talking about instances of co-opting strategies for engaging public space? Or is this a question of abstracting or commodifying those strategies?

The relationship of artists’ use of tactics to those deployed by militant activists is a fascinatingly complex one that varies from artwork to artwork, and artist to artist. Some artists, such as the white Belgian émigré, Jean Toche, co-founder of Guerrilla Art Action Group, define “guerrilla” as the ability to appear and disappear, whereas conceptual artist Adrian Piper never names herself or her art practice under these terms due to the riskiness of such an association as a black woman. Instead, Piper theorizes how xenophobic and racist anxieties culminate in an abstract figuration of hostility in the American imagination. When considering artists’ diverse modes of engagement, I’m ultimately interested in the vanishing point of art: why did artists decide to use guerrilla tactics for art rather than become militants themselves? And when and how is an act of subversion recognized as a gesture of resourcefulness protected under the law, and when is it criminalized as a threat to society? Where’s the line—and what constitutes it?

why did artists decide to use guerrilla tactics for art rather than become militants themselves? And when and how is an act of subversion recognized as a gesture of resourcefulness protected under the law, and when is it criminalized as a threat to society?

I’m also examining how abstraction—an aesthetic device central to modernism—is at work in artists’ turn to tactical and corporeal practices in 1970s performance-based artwork. The abstraction of social encounter marks one of the continuities linking guerrilla art and abstraction in painting and sculpture of the twentieth century; all raise questions that challenge notions of power, perspective, and visibility by testing the limits and conventions of representation, artistic skill, and labor.

Your lecture brings the practices of Chris Burden together with his contemporaries, the East LA–based collective, Asco. Can you talk more about why you chose that pairing?

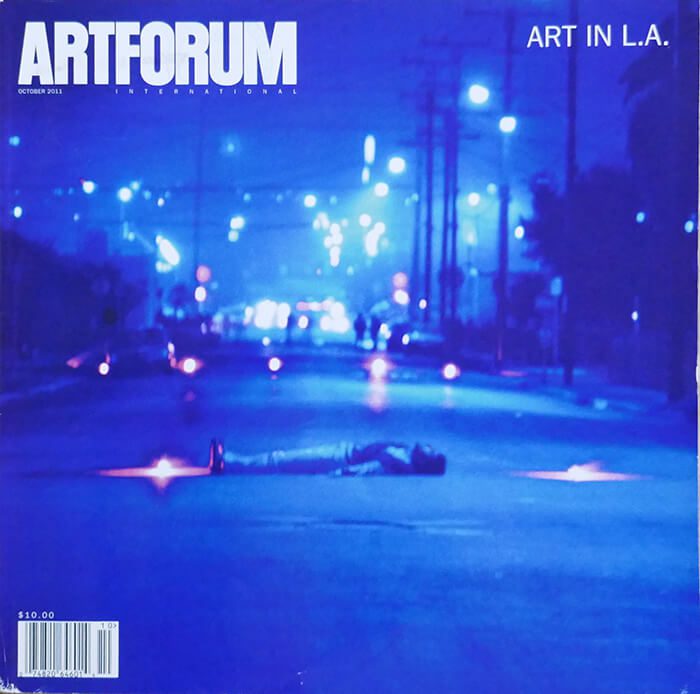

The book is structured around pairs of artists who each use a specific tactic but face different legal and physical consequences, as well as reception within the art world. Chris Burden and Asco each made use of the tactic of hijacking the media but with distinctly different motivations and to different ends. For example, when Burden, a white heterosexual male, held a TV talk show host hostage and later presented this action as a performance piece, TV Hijack (1972), he received only a harsh scolding. Art critics endearingly named him the Evel Knievel of the art world. In grave contrast, when Asco staged Decoy Gang War Victim (1974-5)—a photograph of a fictional scene of gang war aftermath later circulated among news stations as an example of an authentic image—they were upending a chain-reaction of Chicano gang violence instigated by tabloids profiting from the perpetuation of these stories. Asco created images of the aftermath of violent scenes to confront and remedy the inattention given to certain, often non-white, bodies in pain in certain emergency situations. This reorganization of art history reveals each artist’s contribution to the social politics of intervention and the varying consequences each artist faced during the Cold War era of paranoia and xenophobia.

Have you had to carve out more space in the art historical canon to bring artists otherwise separated by medium, discipline, or ethnicity into a dialogue about how they’ve “tested the laws of social order” to various ends?

Yes—typically, art historical studies categorize artists by way of biography, medium specificity, art training, or regional roots. My book builds upon a number of excellent scholarly studies and exhibition catalogues featuring the 1970s, in which all of the artists I analyze—Adrian Piper, Guerrilla Art Action Group, Chris Burden, the Guerrilla Girls, PESTS, Asco, Tehching Hsieh, and William Pope.L—have been included. I seek to realign artists through their shared used of tactics to push the dialogue a bit further and contend with the romanticizing of deviance characteristic of 1970s art interventions. Together, these artworks help us more emphatically see how the institution of whiteness, though not named, is often the social conditioning that motivates artists’ decision to use or avoid tactics that produce face-to-face encounters; to recognize when gender, class, and race intersect in the policing of public spaces; and how performance as a medium has been marginalized in the art-historical archive due to the narrative that, as Coco Fusco has observed, identifies it as “the guerrilla”—the outsider—within dominant art practices, so to speak.

How are you broadening your study to include legal histories, as well as histories of policing and surveillance?

My initial inspiration for this body of research came from learning and writing about the exhibition Illegal America, hosted by Franklin Furnace Gallery in New York City, which surveyed how artists tested a number of laws. Critics’ biggest grievance upon viewing the exhibition was that these artists were all acquitted of charges, including indecent exposure, treason, trespassing, and the destruction of private property. This criticism, in my mind, raises the question: would the artwork have had more of an edge, or garnered more respect, if the artists were imprisoned, and what does this desire reveal? What fantasies govern the potential for, or value of, experimental art practice?

would the artwork have had more of an edge, or garnered more respect, if the artists were imprisoned, and what does this desire reveal?

The artists I analyze each, in different ways, faced off with police for the acts they performed as art works. Often, they were arrested on account of the suspicion and for potential psychological crimes that their actions may become. As a result, I’ve turned to researching “inchoate” crimes, a category of imperfect or not-yet formed actions believed to constitute future crimes. These actions, identified as conspiracy, solicitation, and attempt, were policed in a variety of ways and had a direct bearing on the enactment and treatment of the artists’ tactical art actions in the 1970s.

Even though you’re writing about an extended historical moment, do you feel like your study is relevant to the present?

Absolutely. This older history of guerrilla performance art and its reception sheds light on how the archive effaces how the political governance of public and private space is constituted by racialized, gendered, and classed notions of innocence and deviance. The point being: histories of tactical intervention in the past remain with us. They continue to shape assumptions about the “look” of resistance, resourcefulness, deviance, and creativity and each category’s standards of evaluation. These are not natural or fixed categories, and the images that emerge from them can be used to foreclose upon future modes of intervention. The presentation of a detail image of Asco’s Decoy on the cover of Artforum in 2011 exhibits some of the components of that process of foreclosure—reframing, constructing an archive retroactively, and romanticizing the past. As scholars and artists have long argued, the notion of protecting “safety” is dependent upon the perception of transgressions and threats from some outside force. How notions of inside and outside, citizen and guerrilla, come to be and the various ways that cultural production is a part of this narrative must be examined from every possible vantage point; the history of artists’ deployment of guerrilla tactics and their reception histories help us better understand how the figuration of threat, as well as the regulation of resourcefulness, is co-articulated.