The Future Town Tour, an ongoing series hosted by Warm Cookies of the Revolution, brings residents together throughout small-town Colorado to reflect on shared cultures and create new rituals.

On the second story of a community center in Silverthorne, Colorado, the kids have taken over. They rush at each other wielding swords made from the cardboard centers of cotton candy. A stuffed toy is thrown, again and again, into a cluster of tiny bodies playing some version of the schoolyard game three flies up. The corners of the room are collecting popcorn kernels, crushed chips, and tangles of charging cables.

Downstairs is a comparable cacophony of cheering, clapping, and clacking from folklórico shoes, punctuated by the occasional pop of a balloon animal. On a stage toward the back of the room, two bilingual co-MCs make announcements to a room of Spanish speakers.

The occasion is an end-of-the-year party for Mountain Dreamers, an advocacy organization that provides resources for immigrant residents in Summit County. Tucked around the corner from the giant Christmas tree and next to a holiday-themed photo booth, there’s a plastic pop-up table covered in brochures about less celebratory things—like how to get unemployment benefits as a tax-paying, undocumented worker—that reveals the true meaning of the celebration: it takes a lot of work to look out for one another as a community.

Silverthorne is one of countless small towns in Colorado that have experienced large population fluctuations over the past couple of decades. The forces pressing down on small towns are complex, with some experiencing the squeeze of depopulation as younger generations age out of town, and others feeling the pressure of growing populations, exacerbated by the pandemic’s effects on work culture. Those on the edge of the job market retired early, called it quits or were pushed out; others took advantage of their newly remote jobs. In any case, loads of city dwellers suddenly sought out the small towns where they could live further from people and closer to nature.

Meanwhile, the urban-rural political divide has widened in every presidential election since 1992. According to some studies, the gap between urban and rural voters grew from about 2 percentage points in 1992—meaning voters in rural regions were 2 percent more likely to vote for the Republican candidate—to more than 20 percentage points in 2020. When broken down regionally, voters in the West were split by 19 percentage points.

This has led to the emergence of the “rural voter” as both an individual and a concept—the latter of which politicians, academics, and journalists have painstakingly tried to explain since roughly the George W. Bush administration, not always through good faith efforts.

What all of this means, in the context of a small geographical space, is growing pains. That’s where Adrian H Molina comes in.

Molina was one of the MCs at the Silverthorne event. He is a poet, artist, and the founder of Future Town Tour, a traveling production that brings small-town residents together to envision a common future. The tour works under the umbrella of Warm Cookies of the Revolution, a hydra-headed nonprofit in Denver that makes civics more approachable through lively cultural events.

Forget voting for a minute, what is civics? It’s about us being people together and figuring things out. If people aren’t practicing that in a simple way, how are we going to practice that in a complicated way?

“A lot of people can’t talk about civics or democracy in a simple way, and part of that is because they don’t feel like they’re actually experiencing civics on a simple level,” says Molina. “Forget voting for a minute, what is civics? It’s about us being people together and figuring things out. If people aren’t practicing that in a simple way, how are we going to practice that in a complicated way?”

In other words, if we’re barely talking to our own neighbors, how can we expect to have meaningful national conversations?

The stop in Silverthorne was not on his official tour, but Molina’s work is well known around town. He contributed to Silverthorne’s recent Arts and Culture Strategic Plan, and has been in talks about a future event. Mountain Dreamers tapped Molina to bring some Future Town flair to the party by inviting frequent Warm Cookies collaborators such as aerial ring performers from the Salida Circus, and Stevie Selby, a DJ, photographer, and videographer.

So far, Future Town has visited five Colorado towns over the past two years: Walsenburg, Fort Garland, Center, Alamosa, and Leadville. It’s up to locals to identify what themes and issues they want to tackle, and to recommend artists and organizations they want to highlight. Molina is there to provide the Warm Cookies infrastructure, meaning that each event feels distinct to that town, but also subtly rhymes with the others.

In Center, for instance, a town of about 2,000 people in the San Luis Valley, the tour focused on the issue of retaining its youth population. Since the 1970s, the earliest decade with reliable migration data from the Colorado State Demography Office, the two counties that the town straddles—Saguache and Rio Grande—have experienced steady declines in their 20- to 29-year-old populations. The year 2020 was the first time either county experienced a slight increase in its 20- to 24-year-old populations, likely owing to college-aged students moving home during the pandemic.

So Future Town threw a tailgate party for the local high school football team. But instead of serving up hot dogs and hamburgers, they served horchata and fresh fruit, and hired local cooks to come out and grill. They tailgated Center style—with culturally appropriate dishes, circus performances, and Denver-based hip-hop group 2MX2.

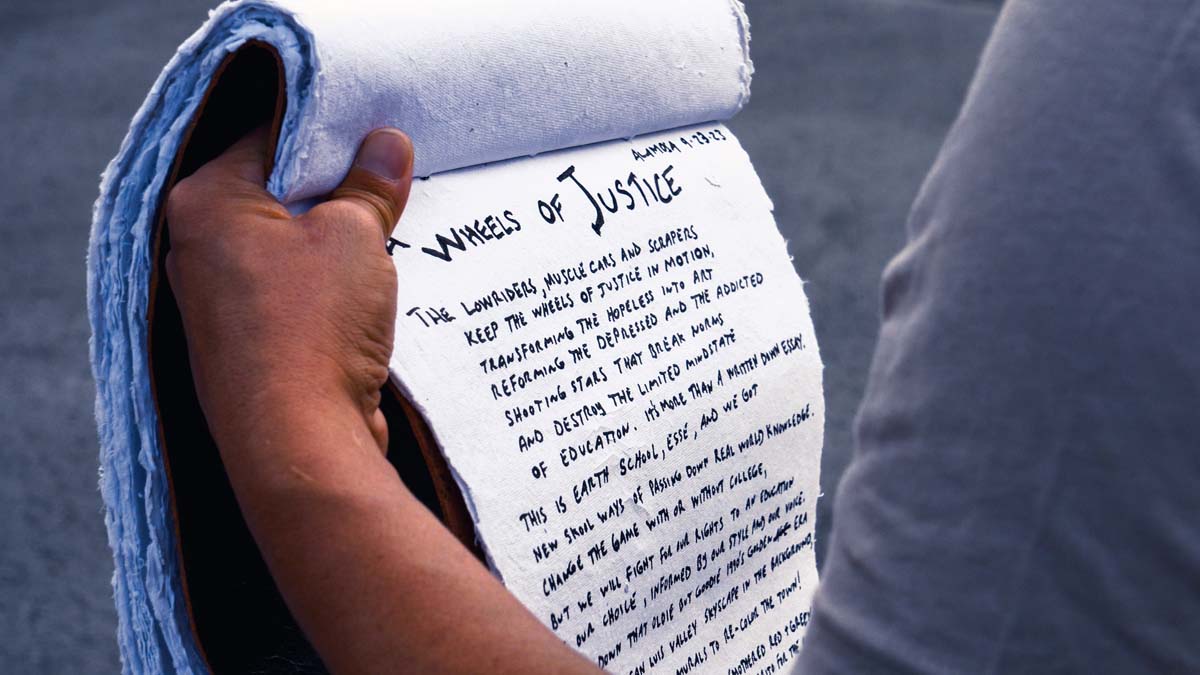

In nearby Alamosa, the community wanted to celebrate its diversity of Spanish-speaking cultures.

“A place like that, you have people who identify as Hispanic, as Mexican, as Mexican American, as Chicano, so on and so forth,” says Molina. “From the outside perspective, it might look like it’s all Latinos down there. But there’s a lot of cultural nuance and a lot of cultural difference.”

The gathering they came up with included the local lowrider club, Tejano musicians, and Aztec dancers and food from Northern New Mexico.

“As much as we need to preserve the old traditions, some of those old traditions come with the sense of who’s in and who’s out. Who’s welcome and who’s not,” says Molina. “I think there’s a deep need for us to break out of traditional tensions, and the only way that we’re going to break out of that is if we do some new stuff together.” It’s about creating new cultural rituals, he added.

It’s also an ongoing experiment, and hasn’t been without error. In 2023, after Future Town’s first-ever event in Walsenburg, an old coal town in southern Colorado, a couple of local women approached Molina.

“They were like, ‘This was really cool. We haven’t seen this many people out since way before the pandemic,’” recalls Molina. But they also had notes. “Then they were like, ‘Straight up, if we don’t address the addiction crisis, if we don’t do something about people’s mental health in this community, none of this shit is going to matter.’”

Future Town returned to Walsenburg in September 2024. This time around, they centered on the theme of community health and healing, and featured a bunch of holistic modalities—qigong, yoga, acupuncture, massage—along with addiction and mental health counselors, and a healthy Southwestern meal: potatoes, green chile, and a massive salad bar.

The idea isn’t to avoid hard conversations about changing community dynamics, whether that’s depopulation, mental health, food access, or housing prices, all issues that different towns along the tour contend with. It’s about letting the Future Town events mitigate those conversations, soften people up to one another through art and entertainment.

“The event is about bringing people out to have a good time, to have a memorable, joyful experience together,” says Molina. “That means when something hard comes up later, there’s already a bond there, you know?”

Art gives people an excuse to let their guards down; shared culture gives people something to bond over.

The fact that the events focus on art, culture, and food is an important component in fostering the type of overall civic engagement that organizers are hoping for. Art gives people an excuse to let their guards down; shared culture gives people something to bond over. Selby, the DJ and photographer, compares the experience to singing with strangers at a concert.

“Maybe you’d never talk to them outside of that context, but you’re both singing the same song. You guys are connected in that moment, on that frequency, on that same vibration,” he says. “Future Town is bringing that same energy… people can start to connect in ways that they wouldn’t otherwise.”

The town of Silverthorne, for its part, has employed some of these tactics in its municipal governance. It experienced steady growth over the past eight years, increasing its population by about 15 percent between 2016—the first year the town created an Arts and Culture Strategic Plan—and 2024, when they published an updated version.

“There are different perspectives on the role of a municipality. Historically, it’s been all about infrastructure,” says Ryan Hyland, town manager of Silverthorne. “But I think if any municipality today is doing it right, they’re thinking about human connection, placemaking, all of those things. That’s harder, right? Those are harder conversations than whether or not we should expand the rec center. It’s about things like equity, things that are a little thornier.”

Hyland is also kicking around more esoteric ideas, like what it means to be a mountain town in 2024. “A lot of people say they don’t want [Silverthorne] to become ‘a city in the mountains,’” says Hyland. But that “mountain culture” means something different to a longtime resident, a recent transplant, and a refugee.

Optimism can’t be empty, it’s got to have some grit to it. So what we bring is both creative process and relentless optimism.

In many ways, Silverthorne has turned to art to help answer those questions of identity. First Fridays in Silverthorne have become a popular way to rub shoulders with neighbors. In 2019, the town purchased a third of an acre along the main drag and turned it into the Art Spot, which opened in 2023, a community center that offers programs, workshops, lectures, art therapy, and other events. A town representative said that between 2015 and 2023, they increased attendance to art and cultural events by 3,000 percent and secured more than $250 million in private investments for arts-forward initiatives, all of which will help the town bring people together more consistently.

Molina understands that some of this can sound a little starry-eyed. That serious economic, social, and political issues won’t be solved because there’s free barbacoa involved. But he also recognizes his role, and the role of artists in general, in creating a shared culture—one that can compassionately, and civically, address those issues.“Pessimism is the tool of people who want to break you down. It’s an oppressive tool, you know?” Molina says. “Optimism can’t be empty, it’s got to have some grit to it. So what we bring is both creative process and relentless optimism. As artists, that’s what we know: we know process, we know practice, we have bold ideas and are into experimentation. We’re not trying to solve anybody’s problem or change anybody’s community. We’re coming to bring the spirit of collaboration.”