M12 Studio’s multi-year collective projects show the complexities of rural places and open conversations about what connects us.

On a clear and mild December day, I met up with Richard Saxton of M12 Studio at the Black Forest Institute installation in Colorado Springs, intercepting him on his drive back home to Denver. It was the first time he had visited the Black Forest Institute since it was constructed. He was dismayed to find both the woodshed and the outdoor fireplace locked.

Wearing a black cowboy hat and a black coat, Saxton shook his head. “Things like this lead me to believe that our institutions are broken,” he says.

Comprised of three elements—a woodshed, an outdoor fireplace, and a workbench—the Black Forest Institute (2021-present) is designed as an outdoor public artwork and “micro campus” for facilitating dialogues and workshops on the topic of forest fires. Located on the grounds of the Ent Center for the Arts on the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs campus, Institute is named for the Black Forest area, northeast of Colorado Springs, once the site of the most destructive forest fire in state history, in 2013, in terms of property lost. The wood in the woodshed was gathered from the burn scar, intended to serve as fuel for “fireside dialogues” that should encourage the sharing of stories and knowledge around wildfires in an age of urban encroachment. While I was writing this article, the Black Forest fire was surpassed as the most destructive fire in Colorado history by the Marshall fire in Boulder County, which saw more than 900 homes destroyed within just six hours.

“What’s the next crisis, is it the food crisis, the climate crisis? The reality is they are all connected,” Saxton tells me.

M12 Studio operates as a collective, or network, of artists, curators, writers, and academics that work together on artworks and long-term research projects that explore place, culture, and rural aesthetics. The collective’s roster currently includes founder Richard Saxton as creative director, curators/editors Margo Handwerker and Matthew Fluharty, grant-writer and program-manager Kirsten Stoltz, digital designer Trent Segura, fabricator Aaron Treher, and artists Marc McCay, George P. Perez, Stuart Hyatt, Mary Rothlisberger, and Christopher Sauter. “I would say philosophically the organization is run collectively,” Saxton says. “We’re usually looking at a geographic region and we’re thinking about place,” he explains, “but being in these rural spaces we also have the goal of really kicking up projects and ideas that are on par with things that are happening coastally.”

Saxton talks about M12 in terms of a cosmos. The collective is comprised of two planets—the studio side and the non-profit side of the collective—in orbit. The non-profit orchestrates multi-year research and education initiatives, with a multitude of outside collaborators and satellite organizations entering its orbit. On the other side, M12 functions as a working studio, or artistic firm, producing one to two projects each year, as commissions or exhibitions. These planets exert influences on each other and pull each other along gravitationally.

“I think the collective vision comes in because we’ve worked really tight to keep some of those things, like expressing rural aesthetics, working toward rural equity, [and] having narratives that haven’t been told, or telling them in a different way with each project,” Saxton says. “Those are maybe more theoretical or philosophical collective ideas that we’ve founded together and have agreed to work with them.”

At the core of M12’s mission is this sense of rural equity. While 18 percent of the population of the United States lives in rural areas, which account for 97 percent of landmass, just 11 percent of NEA funding and only about 5 percent of arts funding from large foundations serve those populations. Not only does the funding fall short, which results in a “hollowing out” of education, cultural instruction, and the arts in schools, Saxton notes, there is a gap in understanding between urban and rural. “We’ve felt that there’s a pretty big misrepresentation of [the] rural,” Saxton says, “beyond an agrarian or pastoral representation, in the canon of American art history.”

We’re not looking for a shiny perfect portrait of anything. We’re kind of looking for the opposite, which can be hard to explain to people. We’re not intentionally trying to confuse things more, [but] rather we’re in the business of unearthing and visualizing the complexities of these places. —Richard Saxton

At the start of a long-term project, M12 will establish a field work site, usually in partnership with a local organization. For their most recent non-profit endeavor, the Landlines Initiative (2018-2022), a project in Colorado’s rural San Luis Valley, M12 set up a site in a small adobe on a ranch in Southern Colorado. From there, Saxton states, the project develops slowly, with one to two years devoted to research of the area before any invitations are extended to other artists. “We are pretty slow and try to be pretty intentional,” he says. In the initial research phase, “we essentially try to draw a conceptual arc around the region,” consult with interdisciplinary experts, and then identify who to invite and where the interpretive projects could take place.

M12 purposefully assembles a constellation of both local voices and artists from outside the region. “If you stay within the regional or provincial, those voices have a hard time getting out,” Saxton explains. “But also if you go the direction of bringing all these artists in [just] to do these cool projects… they don’t tend to have connections with the deeper roots of the place. We’re very particular about who we work with and giving projects time to germinate properly,” he adds.

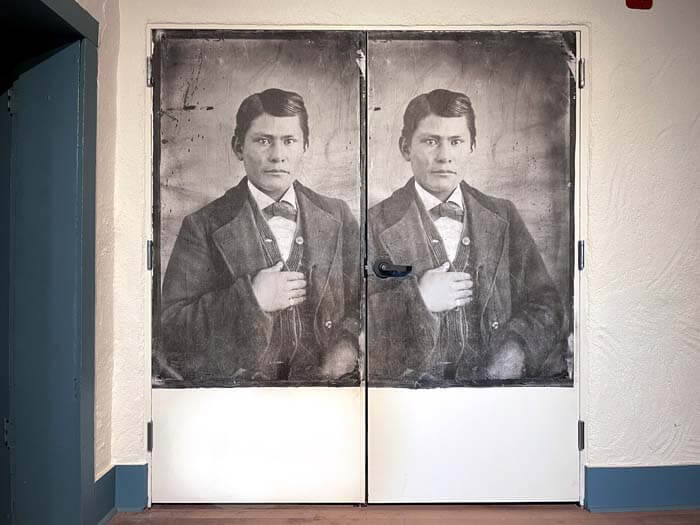

One of the most high-profile projects of the Landlines Initiative is Unsilenced (2021-ongoing) at Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center. A long-standing Kit Carson exhibition was dismantled to make way for an installation by artist Chip Thomas (aka jetsonorama) that reveals the widespread practice of the enslavement of Indigenous people in Southern Colorado well into the 19th century. The exhibition signals a significant shift in the way history could be interpreted and presented at local historical sites such as this, and garnered national attention to a history hidden beneath the familiar narratives of Westward expansion and Anglo conquest. “Basically this is where the wedge of the arts comes in and can be powerful,” Saxton says.

In addition to the idea of rural equity and bringing in major art projects, M12 is focused on narrative building, prompts for dialogue, and building awareness of the cultural significance of often-overlooked rural areas. “We’re not looking for a shiny perfect portrait of anything,” Saxton says. “We’re kind of looking for the opposite, which can be hard to explain to people. We’re not intentionally trying to confuse things more, [but] rather we’re in the business of unearthing and visualizing the complexities of these places.”

“Maybe that’s also what the collective does is make those gray areas, those spots that we can’t see so much, a little bit brighter,” Saxton says, “so we can get a better constellation, a visual that’s not so simplified or canonized.”

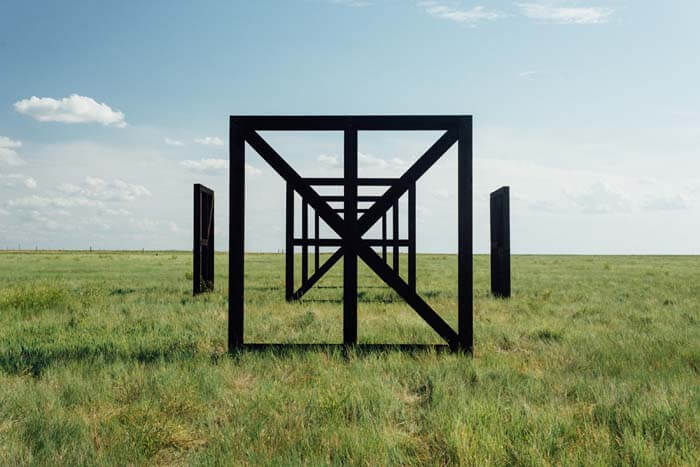

The Landlines Initiative comes to a close in 2022 with the publication of a book compiling the various projects. The next major multi-year project that M12 Studio is now embarking upon concerns the territory over the Ogallala Aquifer, a region that touches eight states: Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

“We’re focusing on the Ogallala not so much as a resource, that clearly isn’t being recharged as quickly as it’s being depleted,” Saxton says, “but as a geological, ecological, and cultural area first, before we talk about the water underground.” The region produces more than a third of the United States’ agricultural output, driven by irrigation systems developed in the 20th century that transformed the Great Plains from semi-arid prairie grasslands to the breadbasket of America. The water reserves from the Ogallala Aquifer, accumulated over thousands of years, have enabled the industrial-agricultural way of life that took hold in the post-war era. But the wells are running dry.

Entitled The Tap, M12 Studio’s project will grapple with ideas of conservation and stewardship and the culture and history of this territory. Describing the stakeholders on this land, Saxton says, “You’ve got [people with] 200-year histories on properties that were bought or earned through proving up the land, and they have a piece of paper, but then you have thousands of years of history of [Indigenous] people living in the region and they don’t have a piece of paper, but they arguably have more of a collective right to that territory. When we form something that looks like a new territory, what kinds of questions can come from that?”

With the rise of Trumpism, the economic toll and cultural schism of the COVID-19 crisis, the failure of institutions, government, and academia to address deep-set inequities, it has become apparent that “the whole vision of a utopic Jeffersonian agrarian America,” Saxton says, “is broken.” There is also, however, no return to an idyllic past, a mythical Arcadian ideal of the American dream. The seeds of division were sown long ago.

But if anything truly does connect us, it may be something deep down—an underground aquifer, a wellspring, a common source. “A huge part of this next project that we’re excited about is trying to visualize something that we can’t see,” Saxton says. “There’s a wonder to it.”