Experimental exPRESSion: Printmaking at IAIA, 1963–1980

July 29, 2019 – July 11, 2021

IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe

My formidable mother, a novelist, used to say, “Life could be so simple, if you let it. Why can’t you ever be simple?” Here’s one way I am simple: Good art makes me happy and optimistic; bad art (art in bad faith), makes me sour and depressed. The passionate, energetic prints on display at IAIA’s Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe make me euphoric. Practically every piece rewards the viewer’s attention.

Printmakers in general are a solitary, eccentric bunch, much like ocelots. They take up fencing in their youth, have a smattering of Latin, Greek, or Sanskrit under their belts, and enjoy esoteric pastimes, when not mixing chemicals in their old stone basements. There are many steps to making a print. What emerges on the other side is frequently not what the artist intended, sometimes less—occasionally much more. This is what hooks people; it’s the secret sauce of printmaking. It is a controlled mixture of primitive chemistry and chaos theory. Experimental Expression: Printmaking at IAIA 1963-1980 is from the collection of Seymour Tubis (1919-1993), who taught printmaking at IAIA from 1963 to 1981. The current show is a selection of the best of his students’ work, donated by his daughter.

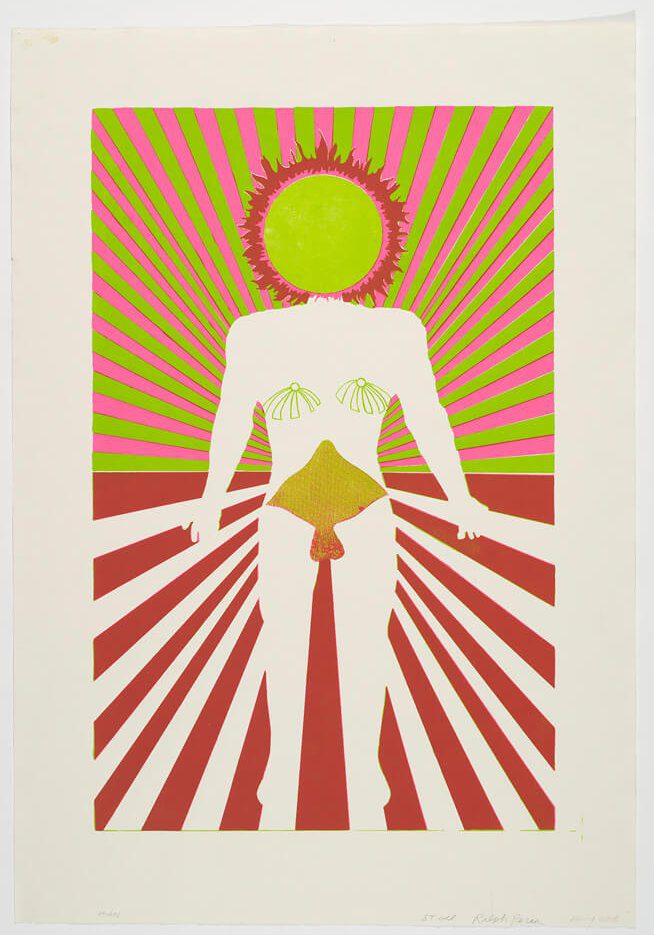

The exhibition is divided into three rooms: the first has a few characteristically bright screenprints (or serigraphs), as well as a wealth of intaglio etchings; the second room has vivid woodcut relief prints, many abstract, some uncommon embossed relief prints; the third room has prints that combine techniques, such as etching and embossing, as in Grey Cohoe’s The Hunted Buffalos. The room contains a handmade book that was a collaboration between printmakers and poets, as well as a student recruitment film for IAIA, which shows students printing giant screens and bathing their metal plates in acid.

The artistry on display is so overpowering that I gave up the printmaker’s game of interrogating the technique used. Every artist has something to say, whether the explorations are formal or emotional. The influence of the psychedelic art movement, of the heady freedom of the ’60s and ’70s, is apparent in many pieces, from Peggy Deam’s pointillist etching, the headless Sitar Player of Mine; Liz Sotlappy’s drypoint in pure Revolver-style line, Birth of an Eye; to Rudy Begay’s untitled drypoint and monotype, using X-ray film as a plate, which juxtaposes a skull and an American flag.

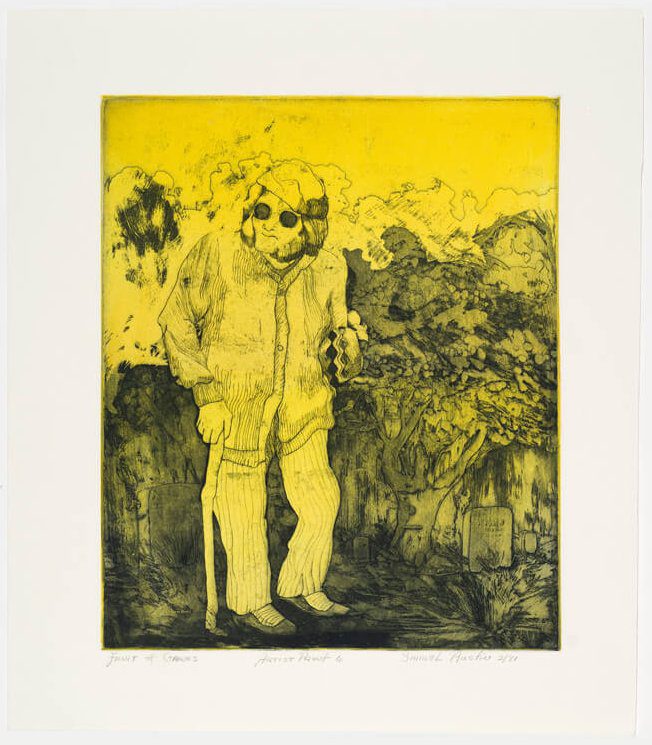

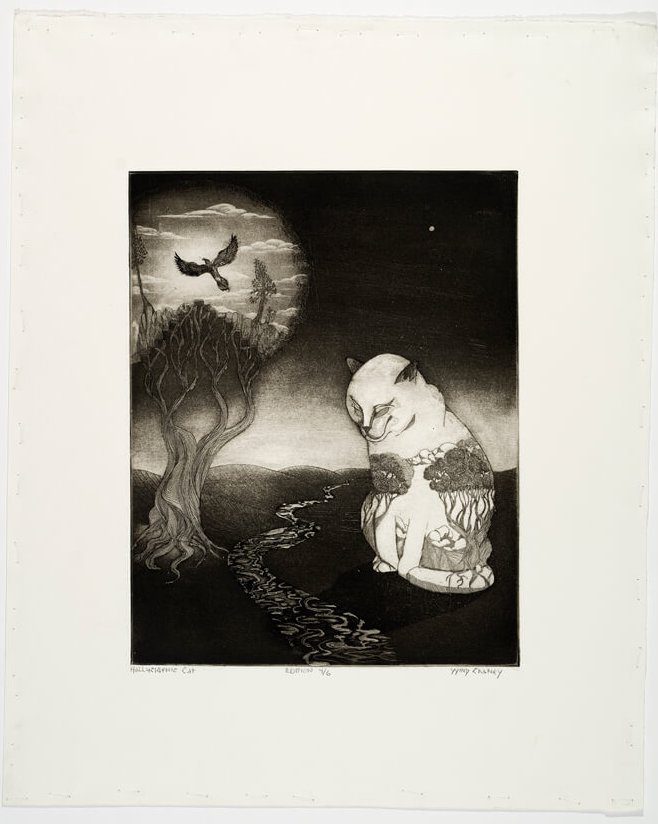

For me, the strongest part of a marvelous exhibition was the etchings, which use only the basic processes: drypoint, (drawing into the metal plate), etching (drawing over a waxy resist, then etching the plate in an acid bath), and aquatint (literally a kind of physical pixelation, for shading). I was instantly attracted to Wind Chaney’s magical Hallucinogenic Cat, with its Alice-in-Wonderland aura, whose enormous cat appears to be dreaming of a nighttime landscape, while the landscape itself seems to be hallucinating. I was amused by Glen LaFontaine’s surreal street scene, She Got Me, an etching from the point of view of a man who was shot, surrounded by monstrous passersby. Another standout was the mysterious Fruit of Graves by Samuel Austin, an etching in yellow and black of a man with dark glasses and cane who stands in front of an overgrown graveyard.

Experimental Expression makes this viewer happy because it is not just the meeting of an inspiring teacher with gifted, ambitious students, like the subject of so many movies. It’s not just a student show, and it’s more than the influence of ’60s psychedelia. It works because it is about the joy of finding your voice, of marrying vision and process, the joy of creativity.